Orson Welles: The most glorious film failure of them all | David Thomson on why Welles still fascinates.

Tag: Orson Welles

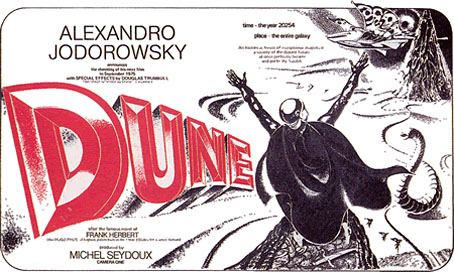

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune

Fortunate Londoners can get to see a new exhibition, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ‘Dune’: An exhibition of a film of a book that never was, which runs at The Drawing Room until October 25, 2009. As well as production designs from concept artists Moebius, HR Giger and Chris Foss, there’s newly commissioned work by artists Steven Claydon, Matthew Day Jackson and Vidya Gastaldon.

Jodorowsky’s proposed 1976 adaptation of the Frank Herbert novel is now the stuff of legend, and it’s possible that his outrageously ambitious plans are more fun to dream about than they would have been on the screen. But it remains a tantalising prospect that Jodorowsky might well have pulled off a science fiction equivalent of Fellini’s Satyricon. Either way, along with Stanley Kubrick’s unmade Napoleon, it’s one of the great lost films of the 1970s.

Among Jodorowsky’s proposed cast were Orson Welles, Mick Jagger and Salvador Dali, the last of whom was to play the Emperor of the Universe, who ruled from a golden toilet-cum-throne in the shape of two intertwined dolphins. Unable to secure the money from Hollywood to create the ‘Dune’ of his imagination, Jodorowsky abandoned the film before a single frame was shot. All that survives of this project is Jodorowsky’s extensive notes, and the production drawings of Moebius, Giger and Foss. These reveal a potential future for sci-fi movie making that eschewed the conservative, technology-based approach of American filmmakers in favour of something closer to a metaphysical fever-dream.

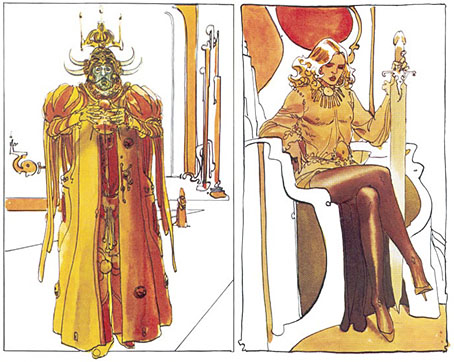

left: Emperor Shaddam IV; right: Feyd Rautha.

Moebius’s designs are wildly different from those used in David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation (which I like nonetheless). His sketch of the Emperor on the left gives some idea of how Salvador Dalí might have appeared in the film, while the figure on the right is Baron Harkonnen’s effete nephew, Feyd, a far more radical conception than the grinning fool played by Sting in the Lynch version. There’s a lot more of Moebius’s sketches at the excellent Dune.info site.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dalí and Film

• Jodorowsky on DVD

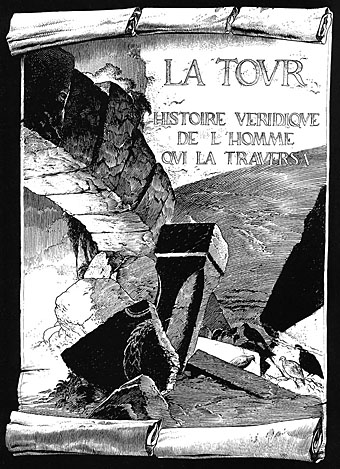

La Tour by Schuiten & Peeters

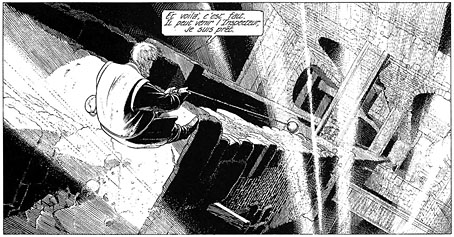

La Tour (1987) by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters is the third story in the Cités Obscures series, although it’s the fourth volume if you want to be strictly canon about things, L’archivist, a guide to places in the Obscure World, having preceded it.

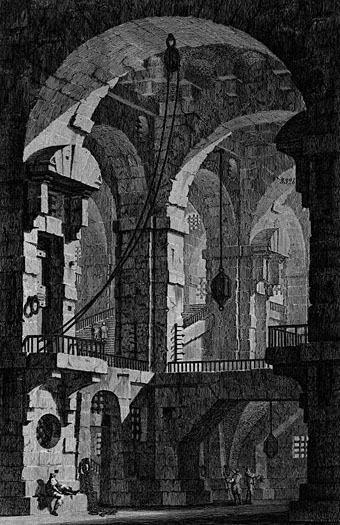

Carcere Oscura by Piranesi (1750).

This is another book where Schuiten and Peeters’ interests tick a list of my own obsessions, being a tale which seems to originate in the question “What would it be like if you crossed Piranesi‘s Prisons etchings with Bruegel’s Tower of Babel?” The protagonist of La Tour, Giovanni Battista, has his name borrowed from Piranesi’s forenames and his appearance taken from Orson Welles’ Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight. The story owes something to Kafka, although it lacks Kafka’s drift towards paradox, concerning a colossal building referred to throughout as The Tower, a structure we only ever see in close-up—and then mostly from the inside—but whose height must reach several thousand feet.

Battista (above) is one of the Keepers, a group of men charged with maintaining small sections of the Tower whose structure suffers continual decay and collapse. Tired of years spent in complete isolation, and concerned that other Keepers aren’t doing their job, Battista goes in search of the Tower’s feared Inspectors, only to discover that the lack of maintenance is endemic and few of the Tower’s scattered residents have any idea of the origin or purpose of the vast building where they’ve spent their lives, never mind a concern for its upkeep. There are no Inspectors, and while Battista is worried at the beginning about vines in the stonework, we later see small forests growing among the ruins. Kafka resonances come with the mention of the mysterious Base, and the equally mysterious Pioneers, those builders and engineers who went ahead years or even centuries before, climbing skyward.

Further farewells

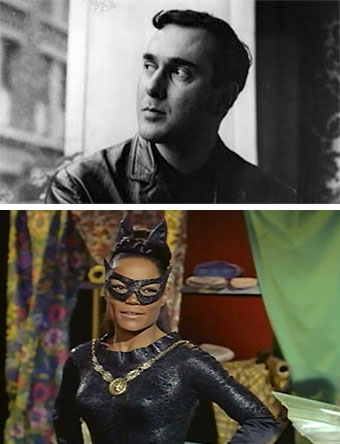

Harold Pinter and Eartha Kitt.

2008: the year that keeps on taking.

The Guardian has a copious collection of Pinter pieces including Michael Billington’s lengthy obituary. Eartha Kitt was just as unique in her own way, prompting Orson Welles in the 1950s to call her “the most exciting woman in the world”. For my sister and I a decade later she was the most exciting Catwoman in the world and that’s how I’ll remember her. But let’s not forget those Cha-Cha Heels…

Eartha’s frivolity might seem to jar beside Pinter’s moral and political seriousness but the World Socialist Web Site managed to link the pair with a priceless headline, Harold Pinter and Eartha Kitt, artists and opponents of imperialist war. Their article tells you a few things about Eartha that many of the obituaries would have ignored. I’m sure Pinter would have been proud to hear of her speaking her mind at the White House. The world is a smaller place when talents and voices like these are gone.

The Panic Broadcast

It was 70 years ago today—October 30, 1938—that Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre traumatised American radio listeners with their brilliant adaptation of The War of the Worlds. I wrote about that recording last year so rather than repeat myself, here’s the final words from Howard Koch’s 1970 book about the play, The Panic Broadcast. (That’s the cover of my cheap paperback edition.) Koch was charged by Welles and producer John Houseman with the task of condensing and updating HG Wells’ novel and he ends his book with an examination of the lessons to be learned from the resulting hysteria. America’s current crop of demagogues on TV and radio—and the audiences prepared to take everything they say at face value—render his words as apposite now as they were forty years ago.

Meanwhile, how can we protect ourselves from politically biased information coming to us through the mass media? It isn’t as simple as dialing another station as in the case of the Martian scare. In my opinion, the only safeguard we have is the cultivation of a skeptical attitude toward all authority, to regard no person or office sacrosanct, to accept nothing that doesn’t accord with our experience and our knowledge acquired from other sources.

Most of my generation were brought up to give unquestioned obedience to authority, whether parental, religious or political. The result has been a compliant and conformist society that has tolerated a war every decade, all sorts of racial and economic inequities and a progressive spoliation of our planet. The management, shall we say, has been less than perfect.

But for the first time there are signs of a change and we have good reason to hope that the world won’t be lost by default. Today all authority is being questioned and challenged, especially by the young. The American people have become more concerned with public affairs on every level. They are taking less on faith; the individual intelligence is beginning to assert itself in self-protection and therein lies the promise of a society with the attributes for survival.

If the nonexistent Martians in the broadcast had anything important to teach us, I believe it is the virtue of doubting and testing everything that comes to us over the airwaves and on the printed pages – including those written by the author of this book.

• The Mercury Theatre on the Air | An archive of the radio shows

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The night that panicked America

• War of the Worlds book covers