The Reverse of a Framed Painting (between 1668 and 1672) by Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts.

• New music with a cinematic flavour: Disciples Of The Scorpion (Main Theme) Heavy Mix by The Rowan Amber Mill is a taster for the group’s forthcoming imaginary soundtrack, Disciples Of The Scorpion (also a sequel of sorts to The Book Of The Lost); The Quietened Dream Palace is this year’s final themed compilation from A Year In The Country. The subject this time is abandoned cinemas, past and present.

• San Francisco Moog: 1968–72 by Doug McKechnie, a collection of early synthesizer music using a modular instrument that was later bought by Tangerine Dream. “The quiescent, meditative pulse of the music has much more in common with what would come to be known as the Berlin school of German electronic music than anything coming out of the US at the time,” says Geeta Dayal.

• Sarah Davachi released a new album recently, Cantus, Descant, so The Quietus asked her to discuss her favourite albums. Related: XLR8R has a mix of the music that Davachi regards as influences. Kudos for the choice of Why Do I Still Sleep by Popol Vuh, an overlooked piece from the end of the group’s career.

When I use relevance as a filter for determining what books to read, I’m failing to make myself available for an authentic encounter with otherness, something genuine art always offers. I’m presuming that I can guess, from the barest plot summary, whether a book will be useful in my life. But how can I know what I will find relevant about a work before I have submitted myself to the experience? I don’t think we are likely to be transformed by art if we try to determine that encounter in advance. Part of the vulnerability necessary for transformation is the recognition that I am, to a great extent, a mystery to myself. How could I know what I need?

Garth Greenwell on the idea that a novel is only worthwhile if it is somehow “relevant”

• “For a long time I had been encouraged by the world of fine art to remove references to the spiritual from my work,” says Penny Slinger in a piece by Hettie Judah exploring the resurgence of interest in occult art. Good to see S. Elizabeth and her book on the subject receiving a mention.

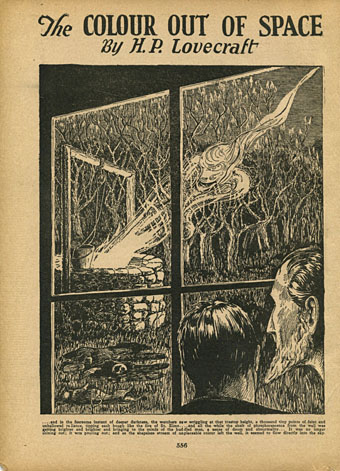

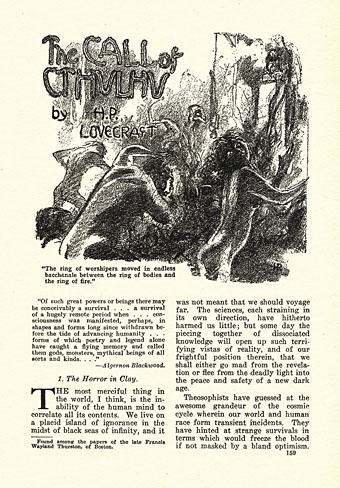

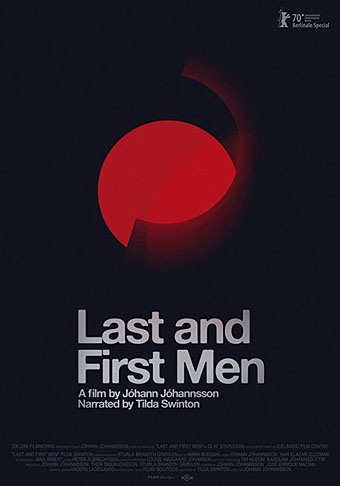

• Arriving on Region B blu-ray later this month is Spring (2014) by Justin Benson & Aaron Moorhead, which 101 Films describes as Richard Linklater channeling HP Lovecraft. I enjoyed Benson & Moorhead’s Resolution (2012) and The Endless (2017) so this one is on pre-order.

• Topical books dept: The Man in the High Chair and Other Tyrannies by Kurt Fawver, a benefit publication for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners.

• We never know exactly where we’re going in outer space: Caleb Scharf on the difficulties of aiming for distant objects in an ever-changing universe.

• Submissions open soon for the contemporary Dada journal Maintenant 15, with a theme of “Humanity: The Reboot”. Details here.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Harry Smith, Filmmaker Day.

• Pandemonium – Spring (1985) by Peter Principle | Silent Spring (2006) by Massive Attack feat. Elizabeth Fraser | Spring Stars (2009) by Simon Scott