A recurrent feature of the music landscape of the late 80s and early 90s was the “soundtrack for an imaginary film”, a sub-genre that proved especially popular among the electronica crowd when DJs realised they needed a description to justify their collections of downtempo instrumentals. Two of my favourite examples were produced away from the dance world: John Zorn’s Spillane (1987), and Barry Adamson’s solo debut Moss Side Story (1989), both of which took their thematic cues from crime novels and film noir. The artists on the Ghost Box label haven’t gone down the imaginary film route but many of the tracks on the Belbury Poly and Advisory Circle albums are reminiscent of TV theme tunes from the 1970s. The closest you get to an imaginary film in the Belbury sphere is the unseen giallo horror in Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio with its score by Ghost Box allies Broadcast, and a title sequence by Julian House.

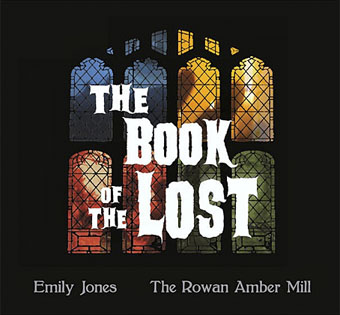

Given all of this, The Book of the Lost, a collaboration between Emily Jones and The Rowan Amber Mill, is a logical next step: a CD collection offering a theme from a forgotten TV series “shown on Sunday nights in the late ’70s and early ’80s” which broadcast four of the equally forgotten horror films upon which the accompanying songs are based. Between each song you hear a brief snatch of dialogue, just enough to whet the appetite without getting too involved. One of the films referred to, The Villagers, belongs to that current of British folk-horror that runs through Witchfinder General, and Blood on Satan’s Claw, to Ben Wheatley’s intoxicatingly weird A Field in England. Pastiching aside, all projects of this kind depend upon the quality of the music, and the folk-inflected songs here are very good, as is the Book of the Lost theme itself which is as spookily evocative as Jon Brooks’ Music for Thomas Carnaki.

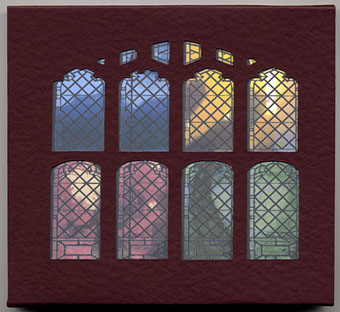

If that wasn’t enough, there’s a special numbered edition of the CD which comes packaged in a die-cut slipcase (above) containing cards giving details of each of the films. In addition to promotional artwork there’s also a synopsis, a production history and even a cast list. Other films are mentioned in passing—The House that Cried Wolf, Ghosts on Mopeds—that imply there was a lot more happening in Wardour Street in the 1970s than we previously suspected.

The Book of the Lost isn’t officially released until January but it’s available for purchase now at the project website.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Outer Church

• The Ghost Box Study Series

• A playlist for Halloween: Hauntology

• The Séance at Hobs Lane

• Ghost Box