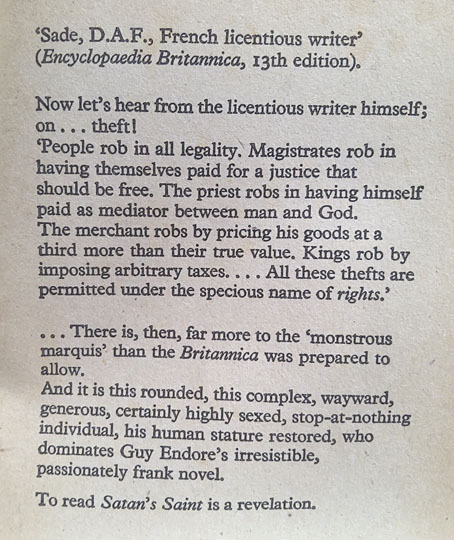

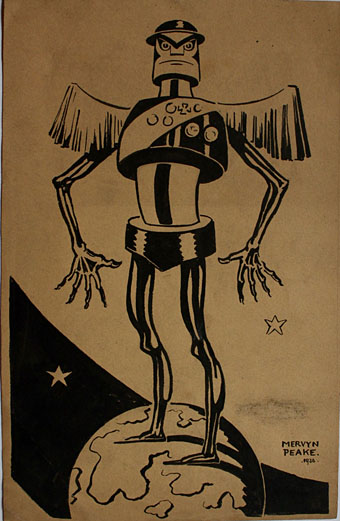

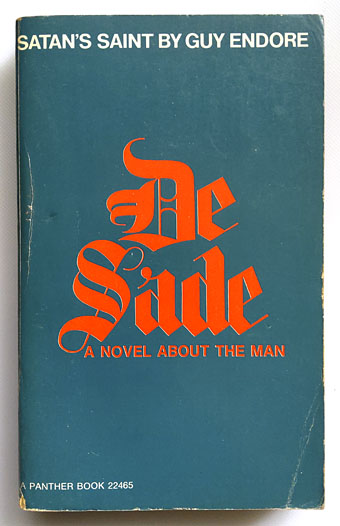

Digging in a box for an errant paperback turned up this volume which I’ve owned for years but never read. Having recently watched Jan Švankmajer’s Lunacy, which has a Sade-like character among its cast, I thought I should give it a proper look. Sade’s irreligious and libertine philosophies haunt the Surrealist world, hence Švankmajer’s interest, Jean Benoît’s performance art and so on. Surrealism didn’t have any saints but it did maintain a pantheon of precursors, with Sade accorded the status of “Genius of Wheels” (ie: revolution) in the Surrealist deck of playing cards.

Guy Endore (1900–1970) wasn’t a genius, a satanist or a saint but he was an interesting character, an American writer best known today for The Werewolf of Paris, another novel I own and have yet to read. He was a vegetarian and a socialist at a time when both these pursuits were regarded with suspicion or outright hostility (his Communist sympathies later caused him to be placed on the Hollywood blacklist). He wrote a great deal of historical fiction—in addition to Satan’s Saint there are novels based on the lives of Casanova, Voltaire and Shakespeare. And his Hollywood credits include work on scripts for Tod Browning (Mark of the Vampire, The Devil-Doll), writing the source novel (Methinks the Lady) that became Otto Preminger’s psychological film noir, Whirlpool, and, with John Balderstone, adapting Maurice Renard’s The Hands of Orlac into the screenplay that became Peter Lorre’s Hollywood debut, Mad Love. The latter is a great film that I’d love to see again. Satan’s Saint was first published in 1965. This Panther edition appeared in 1967. Now I just have to find the time to read it…