I don’t know when I first noticed that the word “introvert” contains the word “invert” but if I require a shorthand self-identification beyond the vocational then “introvert invert” is a suitable candidate. Being an introvert isn’t always easy in a resolutely extrovert world, but being an introvert invert has considerable drawbacks, such as how you meet anyone like yourself when the available meeting places—club and bars—inspire severe loathing. Clubbing is no longer the only option now that we have online dating (and gay clubs have been dying off in any case…) but the options were few in the 1980s. It’s impossible for me to think about any of this without considering that if I wasn’t such an introvert I might not be alive today. I was 20 in 1982 when the AIDS epidemic was starting to travel the world; had I been more gregarious I might have been investigating all those wretched clubs and bars instead of sitting at home, listening to music and drawing pictures.

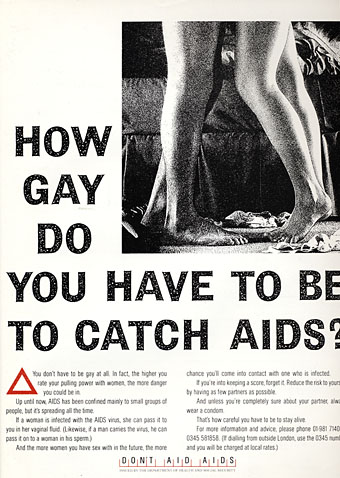

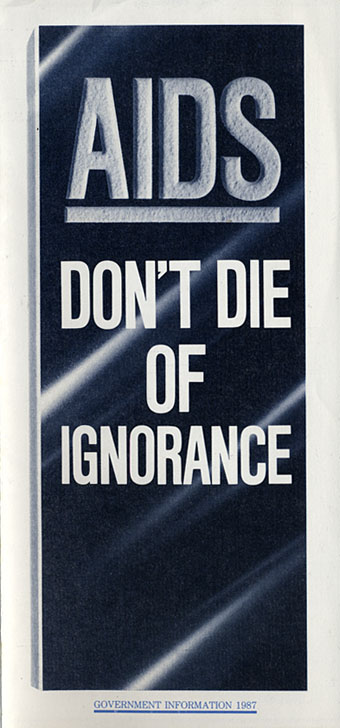

The Thatcher government only started to get serious about HIV/AIDS in 1987 when this information leaflet was delivered to every household in Britain. (See scans of the whole thing here and here.) There was also an accompanying public information film narrated by John Hurt, and directed by Nicolas Roeg, of all people. It was quickly replaced with other films that were less apocalyptic.

Whatever your attitude to nightlife, if you were gay in the 1980s then AIDS was omnipresent even before it became an issue that politicians dared to discuss in public. I remember when Patrick Cowley died (November 1982); I remember when Klaus Nomi died (August 1983); I bought the Panic/Tainted Love single by Coil when it was released (May 1985), the profits of which went to AIDS charity The Terrence Higgins Trust (the first record release to make such a donation). Coil’s doom-laden Horse Rotovator album from 1986 was shaped by the group’s experience of watching many of their friends succumb to illness and death. There were many other such responses, one of the greatest being the monumental Masque Of The Red Death album cycle by Diamanda Galás, dedicated to Galás’s brother and her friends who were killed by the epidemic. I can’t think of artist and writer Philip Core without remembering the interview he gave to The Late Show from his hospital bed in 1989, a hollow-eyed ghost of his former self. The accumulated fear and paranoia of a dark decade lingered into the 1990s even after condom-use had become widespread and HIV became manageable with drug treatments.

More from the fun decade. A government health ad from The Face magazine, February 1987.

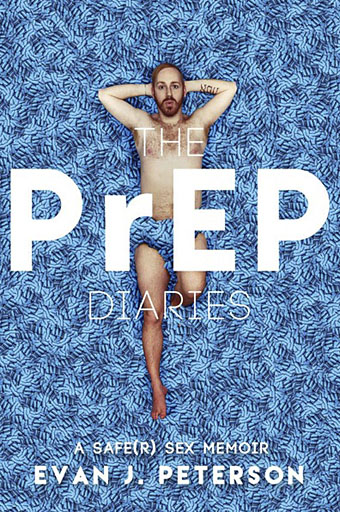

The paranoia of the 1990s is one of the first things that Evan J. Peterson discusses in The PrEP Diaries, an account of growing up gay in America at a time when HIV was treatable but still something to be worried about. Evan is a friend whose previous books have been mentioned here (one of which I contributed to), but this is his first non-fiction title, a witty and enlightening combination of erotic memoir and public service declaration. “PrEP” refers to the drug marketed in America as Truvada, a pre-exposure prophylaxis anti-viral medication which has been gaining use in the US as a preventative treatment for HIV. The drug’s use is recommended primarily to partners of those who are HIV+ but it’s also being recommended to gay men with active sex lives as an additional safeguard against HIV. I’ve been aware of Truvada for several years but since it still isn’t easily available in the UK I’ve not followed the discussion around its use or effectiveness very closely.

One of the reasons for Evan writing The PrEP Diaries was to widen the discussion about PrEP/Truvada by showing how his own use of the medication has helped dispel the paranoia he felt about HIV risks, a paranoia that had been with him since childhood. He was born in 1982, the year that AIDS first began to make headlines so he’s of a generation that has never known a time without the risk of HIV. One of the notable things about his book is the way it shows the substantial differences of experience between the gay and straight worlds, differences that persist even as legislative equality grows. Sexual risk is one of these differences, something you’re always aware of if you’re gay or bisexual but which the straight world seldom considers at all. I have a half-brother who’s a few years older than Evan, and two nephews who are a decade younger; all are straight, and I doubt that any of them have given more than a moment’s thought to the idea that sexual activity could have life-changing consequences even though viruses don’t care about your sexuality. HIV can be kept under control today yet it continues to spread, in part because the serious concerns of previous decades are no longer prevalent. You can’t go on any gay dating site without eventually seeing someone with “poz” in their name or some other indication (usually a + symbol) of their HIV status. One of the benefits of PrEP that Evan discusses is its helping people who are HIV+ to find more partners as well as protecting those partners from infection. He also emphasises something you seldom see mentioned in general discussion of HIV, that positive status doesn’t describe a single condition; some people are positive but undetectable, meaning that their viral load is extremely small.