In the week following the Moon-landing anniversary I’ve been re-reading The First Men in the Moon by HG Wells. This was a late entry in Wells’ extraordinary run of science fiction novels, and is both shorter and lighter in tone than his earlier novels, some of which veer at times into outright horror. The First Men in the Moon might have been a serious examination of interstellar travel but the narrative is overtly comic in places, rather like The Man Who Could Work Miracles, a Wells story in which a fantastic gift is offered to a character unprepared to make the most of it. Wells’ lunar explorers—Bedford, a failed entrepreneur, and Cavor, an absent-minded inventor—lurch from one mishap to another, yoked together through their own inadequacies. Early in the proceedings Cavor destroys his house when his gravity-repelling “Cavorite” generates a violent funnel of air before launching itself into space. Cavor regards this as fortunate, explaining that a slightly different set of circumstances might have removed the breathable atmosphere from the entire planet for a day or so. The trip to the Moon is conducted almost on a whim: Cavor has no real reason for going, and Bedford tags along in the hope of finding some future business opportunity. Like the hapless protagonists of Withnail and I, this is a lunar voyage undertaken “by mistake”.

It’s probable that Wells regarded absurdity as being the best way to approach a story that was less original than his earlier works. The first edition of the novel opens with an epigraph from Lucian’s True History (or True Story), a book from the second century AD which includes a journey to the Moon among its planetary travels. Lucian’s book was the first to feature such a journey (and is often regarded as the first work of science fiction) but many others followed, even before From the Earth to the Moon (1865) by Jules Verne, a book which Bedford mentions during the expedition discussions. (Cavor has never heard of it.)

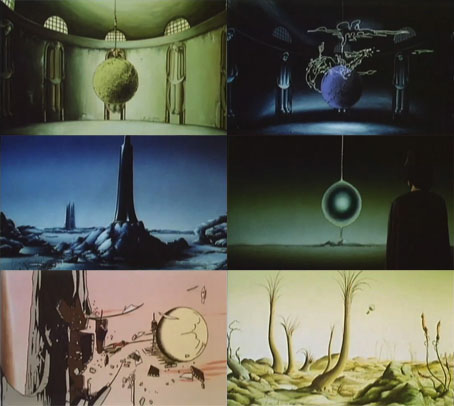

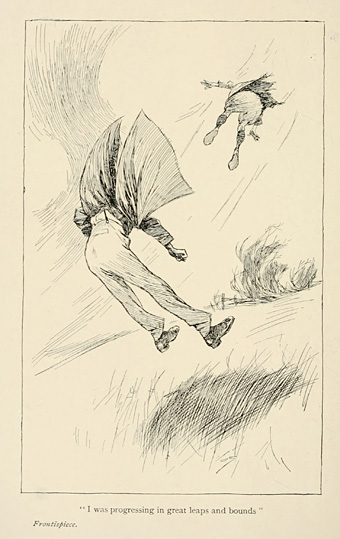

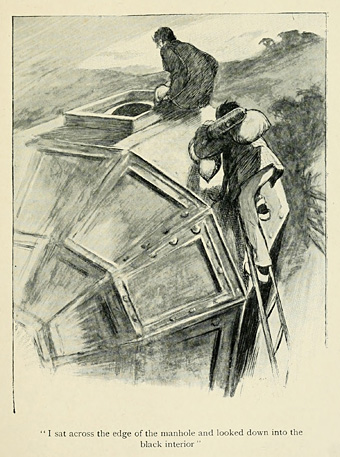

The illustrations here by Claude Allin Shepperson are also from the first edition, and are closer to the tone of the novel than those by other artists. E. Hering’s illustrations for American readers are in a style which is more detailed and inventive than Shepperson’s but which also suggests a more serious story. Readers expecting a new War of the Worlds would have been surprised. Shepperson’s drawing of Cavor’s spacecraft evidently provided the model for Ray Harryhausen in the 1964 film adaptation, although Harryhausen’s Selenites differ from both Shepperson and Wells’ descriptions. Nigel Kneale’s screenplay deviates from the book elsewhere but the film is still a more faithful adaptation than those based on Wells’ more popular novels, as are many of the other screen adaptations, the first being a lost silent from 1919. All of which reminds me that I’ve not seen Harryhausen’s film for many years. I’d welcome another date with the Grand Lunar.

Continue reading “Claude Shepperson’s First Men in the Moon”