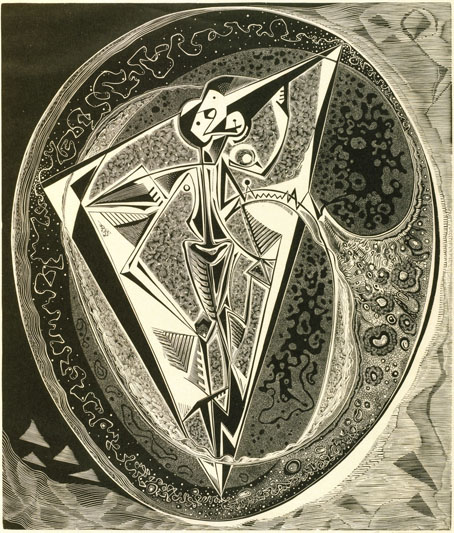

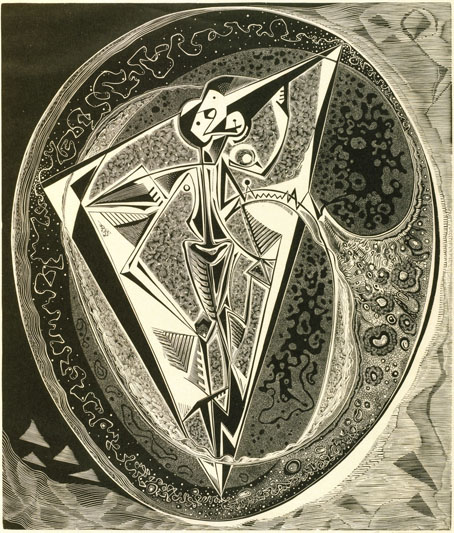

The Yolk (1953) by Gertrude Hermes.

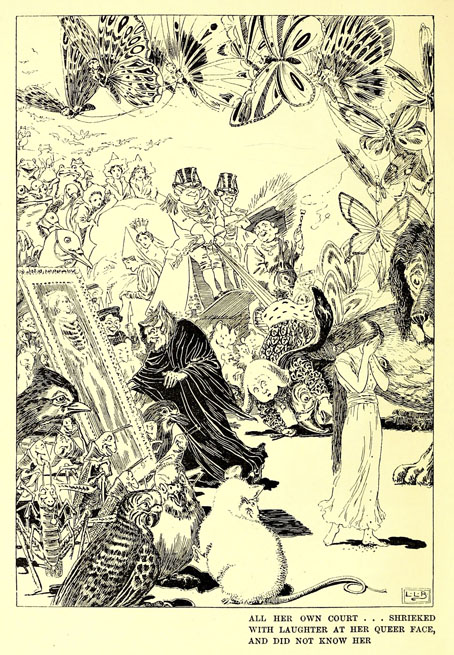

• “By 1910, a quarter of the 129 million litres of alcohol consumed annually by Frenchmen was absinthe. Of course, the wine industry was threatened by this growing desire for ‘industrial spirits.’ The Pernod Company was the primary producer, but there were dozens of distilleries offering variations of the ambrosial concoction. The Green Fairy had become the Green Curse.” Barnaby Conrad III on the intersections of absinthe and art.

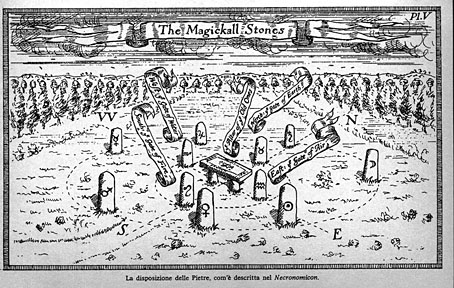

• At Wormwoodiana: “The Zombie of Great Peru is a transgressive novel written in 1697 by Pierre–Corneille Blessebois…a memoir of occultism, seduction, slapstick, and humiliation, set in the racial and sexual hothouse of colonial Guadeloupe. It contains the first appearance of the word ‘zombie’ in literature.” Doug Skinner, the translator of a new edition, talks to Bill Ectric about the book.

• “I have been lucky to have the time to understand, or misunderstand, the concept of sound. It’s all about the sound. I don’t play styles, I don’t play genres, I don’t play jazz. I play my repertoire, my language, my own poetry.” Bill Laswell talking to Paul Acquaro and David Cristol about his career as player and producer.

• New music: Rhan-Tegoth by Cryo Chamber Collaboration. A couple of months ago I was wondering whether Cryo Chamber would be continuing their series of Lovecraftian albums, and, if so, which entity they might choose for the theme of the next one. Now we know.

• “Zines, at their most glorious, are indifferent to dignity, reckless in the statements they reel off, determined to make a virtue of their limited resources.” Sukhdev Sandhu on the history of the fanzine.

• At Unquiet Things: Hazy Shade of Winter: The Artwork of Julius Sergius von Klever.

• Mix of the week: DreamScenes – December 2023 at Ambientblog.

• At the Daily Heller: Daniel Pelavin’s Pipe Dreams.

• Old music: Buchla Christmas by Warner Jepson.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Isaac Julien Day.

• Pipeline (1962) by The Chantays | Pipeline (2005) by Monolake | Banzai Pipeline (2020) by The Surfrajettes