Fractures is the latest musical anthology from A Year In The Country, and having been listening to an advance copy for the past couple of weeks I can say it’s as fine a collection as the label’s previous opus, The Quietened Village. The latter album encouraged a variety of artists to create pieces around the theme of lost or abandoned villages; the theme for Fractures fixates on a year rather than a location:

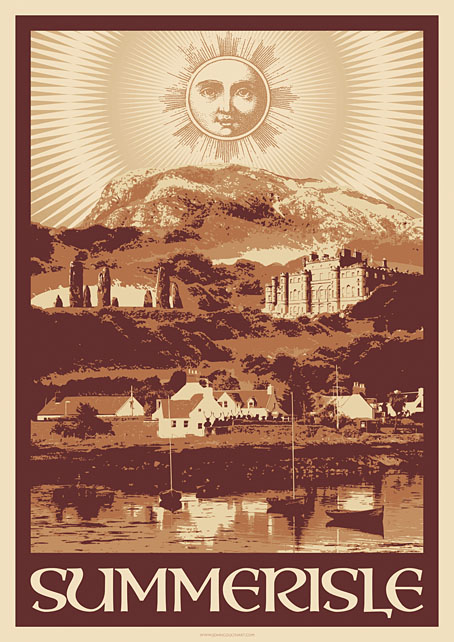

Fractures is a gathering of studies and explorations that take as their starting point the year 1973; a time when there appeared to be a schism in the fabric of things, a period of political, social, economic and industrial turmoil, when 1960s utopian ideals seemed to corrupt and turn inwards. […] Fractures is a reflection on reverberations from those disquieted times, taking as its initial reference points a selected number of conspicuous junctures and signifiers: Delia Derbyshire leaving The BBC/The Radiophonic Workshop and reflecting later that around then “the world went out of time with itself”. Electricity blackouts in the UK and the three day week declared. The Wicker Man released. The Changes recorded but remained unreleased. The Unofficial Countryside published. The Spirit Of Dark And Lonely Water released.

Track list:

1) The Osmic Projector/Vapors of Valtorr – Circle/Temple

2) The Land Of Green Ginger – Sproatly Smith

3) Seeing The Invisible – Keith Seatman

4) Triangular Shift – Listening Center

5) An Unearthly Decade – The British Space Group

6) A Fracture In The Forest – The Hare And The Moon ft Alaska/Michael Begg

7) Elastic Refraction – Time Attendant

8) Ratio (Sequence) – The Rowan Amber Mill

9) The Perfect Place For An Accident – Polypores

10) A Candle For Christmas/311219733 – A Year In The Country

11) Eldfell – David Colohan

This isn’t the first time a year has been isolated as a basis for a musical anthology but prior examples such as Jon Savage’s Meridian 1970 are invariably concerned with the musical scene alone. Fractures is different for trying to seize the essence of the year itself even if a number of the musicians involved may not have been alive in 1973.

The year has a resonance for me that I recounted in the memorial post for David Bowie. That summer was significant (and therefore memorable) for being warm, carefree and positioned between the end of junior school and the beginning of secondary school. The years after those few weeks were increasingly bad on a personal level so 1973 for me spells “fracture” in more ways than one. None of this can be communicated by Fractures, of course, the contents of which have more of a cultural focus: A Fracture In The Forest by The Hare And The Moon sets readings from Arthur Machen to music, while The Land Of Green Ginger by Sproatly Smith draws in part upon a TV film of the same name that was broadcast in the BBC’s Play For Today strand. As those Plays For Today recede in time they seem increasingly like a dream of Britain in the 1970s, reflecting back in a concentrated form much more of the nation’s inner life than you get from today’s Americanised fare. Another Play For Today, Penda’s Fen, was being filmed in the fields of England in the summer of 1973 so we can add the crack in the church floor to the catalogue of fractures. (And for an additional musical entry, I’d note the astonishing Fracture by King Crimson, not released until 1974 but most of the track was a live recording from Amsterdam in November of the previous year.)

Fractures is available from the usual sources such as Bandcamp but hard copies are also being distributed via the Ghost Box Guest Shop.