“Everything about her was white.” Illustration by Edmund Dulac for

The Dreamer of Dreams by Queen Marie of Roumania (1915).

A major exhibition of British fantasy illustration opens at the Dulwich Picture Gallery this Wednesday, running to February 17th, 2008. Considering the huge resurgence of popularity in fantasy for children I’m surprised none of the UK galleries have done this before now. The Dulwich organisers have chosen a suitably wintry picture by the wonderful Edmund Dulac to promote the exhibition which—intentionally or not—happens to look like a precursor of the poster art for The Golden Compass.

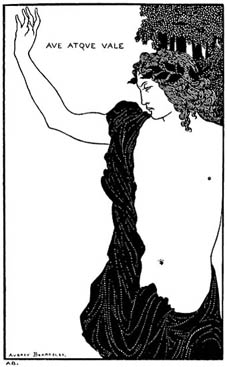

With the death of Aubrey Beardsley in 1898, the world of the illustrated book underwent a dramatic change. Gone were the degenerate images of scandal and deviance. The age of decadence was softened to delight rather than to shock. Whimsy and a pastel toned world of childish delights and an innocent exoticism unfolded in the pages of familiar fables, classic tales and those children’s stories like The Arabian Nights and Hans Andersens’ Stories. These were published with lavish colour plates and fine bindings: these were the coffee table books of a new age.

As a result a new generation of illustrators emerged. This new group of artists was intent upon borrowing from the past, especially the fantasies of the rococo, the rich decorative elements of the Orient, the Near East, and fairy worlds of the Victorians. The masters of this new art form were artists like Edmund Dulac and Kay Nielson, whose inventive book productions, with those of Arthur Rackham, became legendary. Disciples gathered, like Jessie King and Annie French, the Scottish masters of the ethereal and the poetic, the Detmold Brothers, masters of natural fantasy, as well as those who remained in Beardsley’s shadow: the warped yet fascinating works of Sidney Sime, a joyously eccentric coal-miner turned artist, Laurence Housman, master of the fairy tale, the precious inventions from the classics by Charles Ricketts, the Irish fantasies of Harry Clarke, himself a master of stained glass as well as the gift book, and the rich and exotic world of Alaistair. Children’s stories were transformed by the imaginations of a group still bowing to the Victorians Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway and the fairies of Richard Doyle but these were now given a more colourful intensity by Charles Robinson, Patten Wilson, Anning Bell, Bernard Sleigh and Maxwell Armfield.

The exhibition of British fantasy illustration will be the first such exhibition in Britain and the first worldwide for over 20 years (the last being in New York in 1979). All works, of which over 100 are planned, will come largely from British museums and private collections, many of these will never have been seen publicly before in Britain.

The exhibition is curated by Rodney Engen.

AS Byatt reviewed the exhibition for The Guardian and also looked at the sinister perversity underlying many of the Edwardian fairy tales.

• Edmund Dulac at Art Passions

Books by Queen Marie of Roumania:

• The Dreamer of Dreams (1915; illus: Edmund Dulac)

• The Stealers of Light (1916; illus: Edmund Dulac)

• Vom Wunder der Tränen (1938; illus: Sulamith Wülfing)

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Masonic fonts and the designer’s dark materials