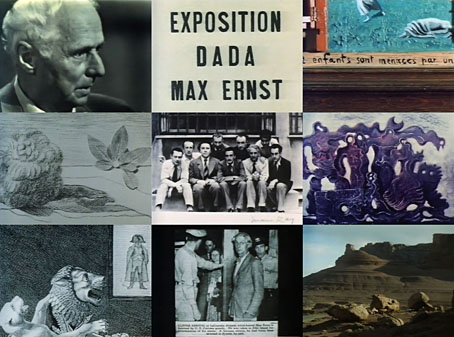

The English version of Peter Schamoni’s feature-length documentary from 1991 has finally reached YouTube. I think copyright reasons may have prevented it from doing so in the past in which case the usual caveats apply: if it’s of interest then watch it while you have the opportunity, it may not be there for long. The German version of the film has a longer title, Max Ernst: Mein Vagabundieren—Meine Unruhe, which auto-translates to “my vagabonding—my restlessness”, a reference to Ernst’s peripatetic life as well as to his artistic wanderings.

I mentioned in the previous post my having spent some time last year watching a number of documentaries about Surrealism. This was one of them, and it’s the film about Max Ernst. Films about Salvador Dalí are plentiful but other Surrealist artists are lucky if they receive a single worthwhile appraisal. Peter Schamoni had filmed Ernst in 1966 for a short, Maximiliana oder die widerrechtliche Ausübung der Astronomie, so was already sympathetic to the artist’s work. Max Ernst resembles one of the BBC’s classic Arena documentaries in being a biographical account threaded with documentary material and pictures of significant artworks. Detail is supplied by actors reading from writings by Ernst, Dorothea Tanning and others.

There’s a lot of interview footage here, mostly from TV appearances in later life, in which Ernst’s intelligent conversation makes a striking contrast to Dalí’s bluster and evasions. Schamoni interleaves the historical footage with shots of the various locations of Ernst’s wanderings: the south of France, New York City, California, Arizona, Paris. Several of the Dalí documentaries note the degree to which the coastal landscape of Cadaqués informed Dalí’s painting; Schamoni makes a similar comparison between Ernst’s American paintings and the desert landscapes of Arizona. It’s good to see some of the Microbes that he painted while he was there, a series of tiny landscape pictures that books about Ernst don’t always mention, let alone reproduce.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The nightingale echo

• Max Ernst’s favourites

• Viewing View

• Max Ernst album covers

• Maximiliana oder die widerrechtliche Ausübung der Astronomie

• Max and Dorothea

• Dreams That Money Can Buy

• La femme 100 têtes by Eric Duvivier