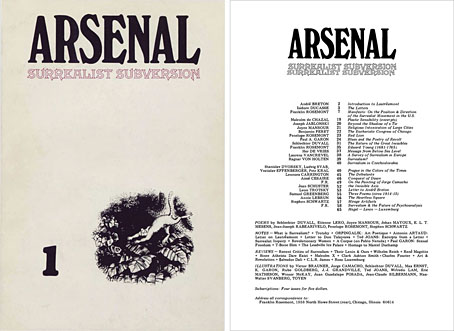

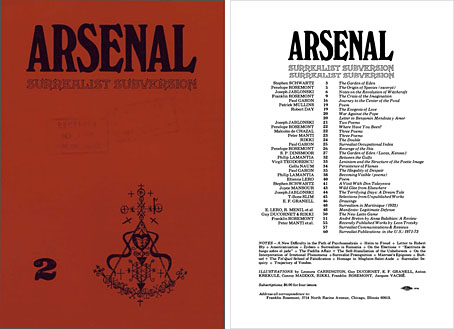

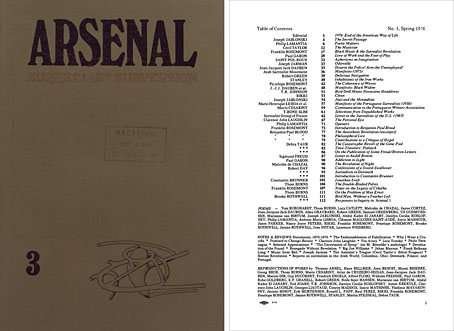

It’s the “S” word again. I said at the beginning of this month that I was looking forward to seeing where this interest led, and here we are. My recent reading has included Penelope Rosemont’s Surrealist Women (1998), a comprehensive study that I’d dipped into in the past but hadn’t gone through properly until now. In the section devoted to activities since the 1960s Rosemont mentions a magazine, Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion, which she produced with her husband, Franklin Rosemont, as part of their work with the Chicago Surrealist Group. Arsenal had more of an erratic schedule than most magazines, managing four issues that appeared in 1970, 1973, 1976 and 1989. I really didn’t expect there to be copies of such an obscure publication available anywhere but, once again, the invaluable Internet Archive has scans of the first three issues.

Arsenal proves to be a curious mix of the kind of material you’d expect from a Surrealist publication—poetry, essays, drawings, collages, significant quotes—together with chunks of Marxist politics and Freudian business that seem to have strayed in from another magazine. The latter material isn’t so unwarranted, being a reflection of André Breton’s original concerns, but committed Marxists of whatever stripe have never had much time for Surrealist art-creation and game-playing, while Freud himself was nonplussed by Breton’s attempts to interest him in the activities of the Parisian Surrealists. Breton casts a long shadow here; the Rosemonts had met him in Paris in the mid-60s, and many of the articles (also their combative attitudes) have a Bretonian cast.

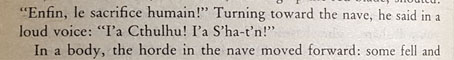

Elsewhere, Arsenal breaks new ground with a Surrealist appraisal of blues musicians, music being a form that Breton and Louis Aragon had dismissed in the 1920s as “too confusing” for incorporation into the Surrealist project. The magazine also reprints a couple of comic strips, including a page of Little Nemo in Slumberland which may be the first acknowledgement from inside Surrealism of Winsor McCay’s dream-worlds as Surrealist precursors. And after posting Breton’s musings about “The Great Transparent Ones” these mysterious beings surface once again. Not only the Great Transparent Ones but also HP Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones in a piece by Franklin Rosemont about the Cthulhu Mythos. Rosemont draws attention to the obvious similarity between the names of Breton and Lovecraft’s beings, while also noting Lovecraft’s prowess as a transcriber of dreams. In doing so he complains about Lovecraft circumscribing his imagination by resorting to the story structures of the pulp magazines. Lovecraft was never a member of any avant-garde literary circle, however, unlike Clark Ashton Smith, who also receives further mention in these pages; if it wasn’t for Weird Tales we never would have heard of HP Lovecraft and there wouldn’t be a Cthulhu Mythos. This fault-picking is typical of many other pieces in the magazine, the book reviews in particular where a kind of petulant bad temper is the predominant tone. You probably can’t expect much else from a magazine that names itself after a store of weapons but the cumulative effect makes it seem that the road to the Marvellous must be paved with razor blades and broken glass. To their credit, the editors did print in the third issue some of the negative reviews they received for the previous two, including the inevitable dismissals from hardline Communists. Despite all this I’d still like to see how things developed (or came to an end) in the fourth and final issue.

• Further reading: I Could Dream In French: An Interview With Penelope Rosemont.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• First Papers of Surrealism

• The original Cabaret Voltaire

• View: The Modern Magazine