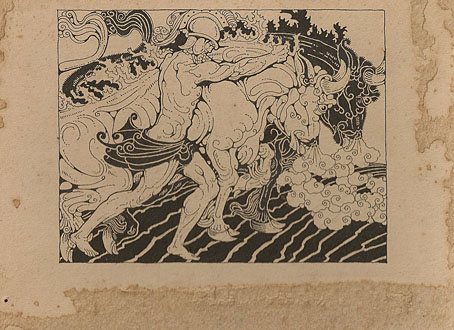

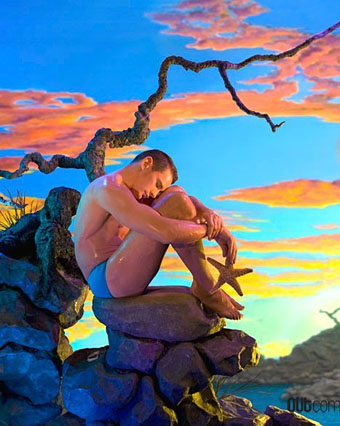

The Golden Porch (1925).

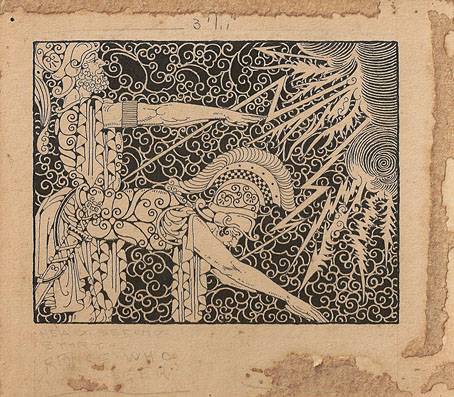

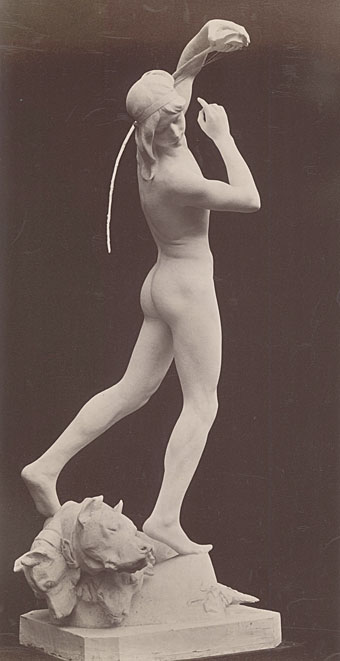

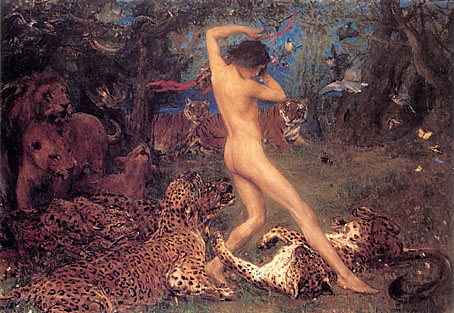

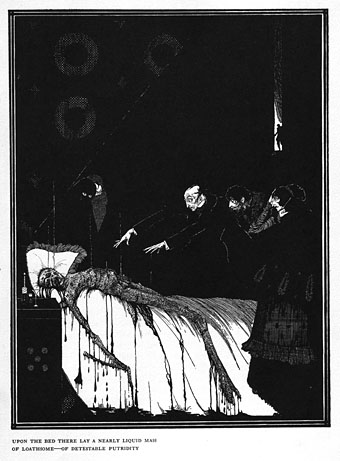

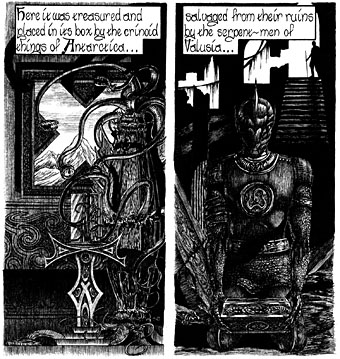

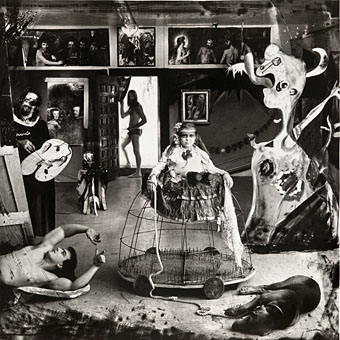

A post prompted by an email from Deborah Hirsch who wrote to tell me about some original works she’d found by American illustrator Dugald Stewart Walker (1883–1937), scans of which are shown here with her permission. This has made me take another look at Walker’s drawings, many of which I’d overlooked during earlier searches. His body of work runs from the usual fairy-tale illustration to some very fine renderings of tales from Ancient Greece. He was also an excellent peacock illustrator although you’ll have to look elsewhere for those; Golden Age Comic Book Stories has made several postings of his book plates. The drawings shown here are from Snythergen (1923) by Hal Garrott, The Golden Porch (1925) and Orpheus with His Lute (1926), both by WML Hutchinson.

The Golden Porch (1925).

Every so often an artist’s work sets me wondering about their sexuality, a consideration which agitates some, especially surviving relatives, who find such speculation to be unwarranted or vulgar. The matter is relevant for two reasons: firstly, if an artist turns out to be gay or bisexual (as was the case with Hannes Bok) then certain details in their work become informed by that knowledge. Secondly, there’s still a lot more work to be done in retrieving from history the lives of gay people who have added to our culture in some way. Illustrators receive little attention in this area since illustration has always been the poor cousin to gallery art. I try to be wary of projecting my own concerns onto an artist for whom such attention may be unwarranted, and I’m not saying one can read anything substantial into Walker’s life simply by looking at his pictures. I do, however, have a mental checklist for any gay vs. straight appraisal which includes among its subjects common themes such as Greek myths (especially those concerning Orpheus and Narcissus), a recurrence of nude males, excessively florid décor, etc. Let’s just say that certain aspects of Walker’s work are (as Sherlock Holmes would say) “suggestive”, and the ex libris plate at the end of this post is notable for illustrating Keats’ famous quote about truth and beauty with a peacock and a (nude?) boy. If anyone has any relevant details about Dugald Stewart Walker’s life, as always they’re encouraged to leave a comment.

• A Dugald Stewart Walker set at Flickr

• Dream Boats and Other Stories (1920) at the Internet Archive