Composition: Cones and Spirals (1929) by Edward Alexander Wadsworth.

• “Repeating items over and over, called maintenance rehearsal, is not the most effective strategy for remembering. Instead, actors engage in elaborative rehearsal, focusing their attention on the meaning of the material and associating it with information they already know.” John Seamon on the vicissitudes of memory, and how actors remember their lines.

• “Mary McCarthy described it as ‘Fabergé gem, a clockwork toy, a chess problem, an infernal machine, a trap to catch reviewers, a cat-and-mouse game, and do-it-yourself novel’, among other things.” Mary Gaitskill on the pleasures and difficulties of Nabokov’s greatest novel, Pale Fire. Also a reminder that I ought to read it again.

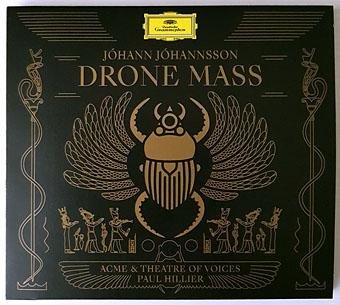

• New music: Movement, Before All Flowers by Max Richter; A Thread, Silvered And Trembling by Drew McDowall; Unspeakable Visions by Michel Banabila.

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: Ulysses by James Joyce.

• The latest cartographical design from Herb Lester Associates is Facts Concerning HP Lovecraft and His Environs.

• At the Daily Heller: A look back at the craze for poster stamps.

• Mix of the week: A tuning mix for The Wire by Tashi Wada.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Michael Lonsdale Day.

• Annie Hogan’s favourite music.

• Clockworks (1975) by Laurie Spiegel | Tin Toy Clockwork Train (1985) by The Dukes Of Stratosphear | Clockwork Horoscope (2008) by Belbury Poly