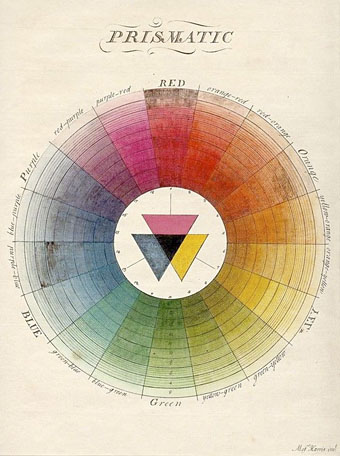

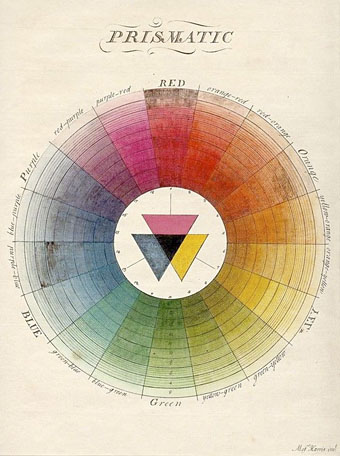

Colour wheel from The Natural System of Colours (1766) by Moses Harris.

• The Vatican’s favourite homosexual, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, receives the ludicrously expensive art-book treatment in a huge $22,000 study of the Sistine Chapel frescos. Thanks, but I’ll stick with Taschen’s XXL Tom of Finland collection which cost considerably less and contains larger penises. Related: How Taschen became the world’s most famous erotic publishers.

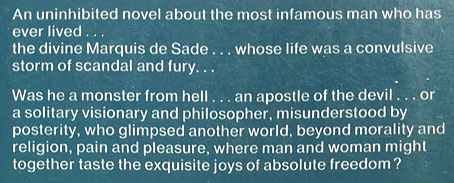

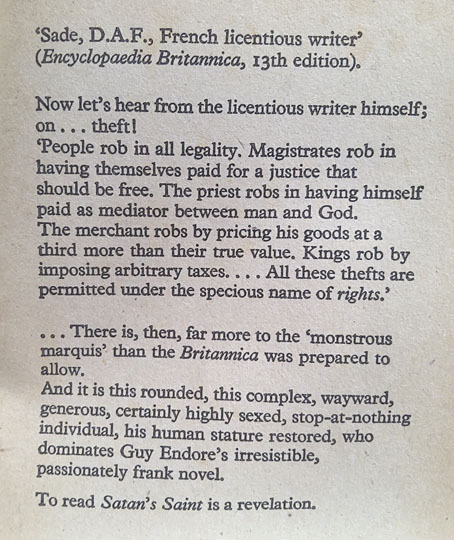

• “In a metaphorical sense, a book cover is also a frame around the text and a bridge between text and world.” Peter Mendelsund and David J. Alworth on what a book cover can do.

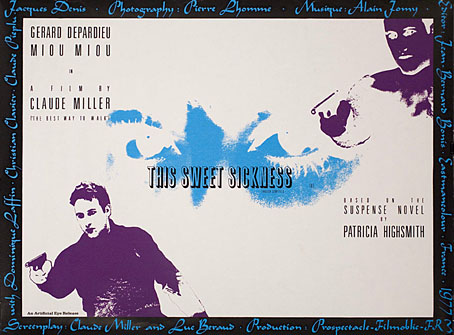

• The Night Porter: Nazi porn or daring arthouse eroticism? Ryan Gilbey talks to director Liliana Cavani about a film that’s still more read about (and condemned) than seen.

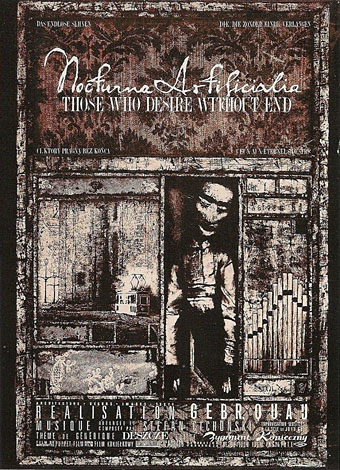

What is important about reading [Walter] Benjamin’s texts written under the influence of drugs is how you can then read back into all his work much of this same “drug” mind-set; in his university student days, wrangling with Kant’s philosophy at great length, he famously stated, according to Scholem, that “a philosophy that does not include the possibility of soothsaying from coffee grounds and cannot explicate it cannot be a true philosophy.” That was in 1913, and Scholem adds that such an approach must be “recognized as possible from the connection of things.” Scholem recalled seeing on Benjamin’s desk a few years later a copy of Baudelaire’s Les paradis artificiels, and that long before Benjamin took any drugs, he spoke of “the expansion of human experience in hallucinations,” by no means to be confused with “illusions.” Kant, Benjamin said, “motivated an inferior experience.”

Michael Taussig on getting high with Benjamin and Burroughs

• “Utah monolith: Internet sleuths got there, but its origins are still a mystery.” The solution to the mystery—if there is one—will be inferior to the mystery itself.

• After Beardsley (1981), a short animated film about Aubrey Beardsley by Chris James, is now available on YouTube in its complete form.

• Mix of the week: The Ivy-Strangled Path Vol. XXIII – An Ivy-Strangled Midwinter by David Colohan.

• Charlie Huenemann on the Monas Hieroglyphica, Feynman diagrams, and the Voynich Manuscript.

• Katy Kelleher on verdigris: the colour of oxidation, statues, and impermanence.

• A trailer for Athanor: The Alchemical Furnace, a documentary about Jan Svankmajer.

• All doom and boom: what’s the heaviest music ever made?

• At Strange Flowers: Ludwig the Second first and last.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Krzysztof Kieslowski Day.

• Ralph Steadman’s cultural highlights.

• RIP Daria Nicolodi.

• Michael Angelo (1967) by The 23rd Turnoff | Nightporter (1980) by Japan | Verdigris (2020) by Roger Eno and Brian Eno