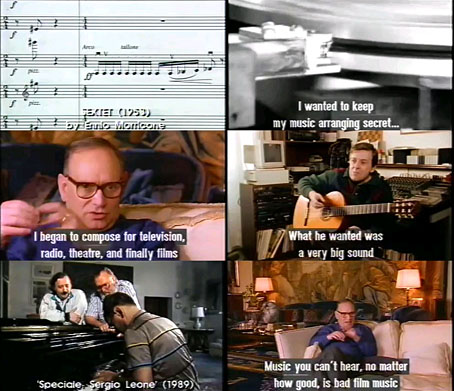

David Thompson made this 40-minute Ennio Morricone documentary for the BBC in 1995. I taped it at the time but haven’t watched it since so it was good to find again. The highlight is the lengthy interview with the man himself but there are also contributions from Christopher Frayling, Brian de Palma, Bernardo Bertolucci, Gillo Pontecorvo and others.

Category: {film}

Film

Maestro

![]()

RIP. There’s no such thing as too many Morricone discs. These are what I’d call a good start.

• Someone had to do it: Alexis Petridis dares to compile a list of 10 great Ennio Morricone compositions.

• At The Quietus: 13 artists and writers on their favourite Morricone compositions.

Weekend links 524

Letter M from Abeceda (1942) by Jindrich Heisler.

• At the BFI: Matthew Thrift chooses 10 essential Ray Harryhausen films. “This is, I can assure the reader, the one and only time that I have eaten the actors. Hitchcock would have approved,” says Harryhausen about eating the crabs whose shells were used for Mysterious Island. Meanwhile, Alfred Hitchcock himself explains the attraction and challenges of directing thrillers.

“Although largely confined to the page, Haeusser’s violent fantasies were even less restrained, his writings littered with deranged, bloodthirsty, scatological scenarios.” Strange Flowers on Ludwig Christian Haeusser and the “Inflation Saints” of Weimar Germany.

• Death, Pestilence, Emptiness: Putting covers on Albert Camus’s The Plague; Dylan Mulvaney on the different design approaches to a classic novel.

• A trailer (more of a teaser) for Last and First Men, a film adaptation of Olaf Stapledon’s novel by the late Jóhann Jóhannsson.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…James Purdy: The Complete Short Stories of James Purdy.

• Al Jaffee at 99: Gary Groth and Jaffee talk comics and humour.

• Steven Heller on Command Records’ design distinction.

• Czech Surrealism at Flickr.

• Solitude by Hakobune.

• Mysterious Semblance At The Strand Of Nightmares (1974) by Tangerine Dream | Mysterious Traveller (Dust Devils Mix) (1994) by System 7 | The Mysterious Vanishing of Electra (2018) by Anna von Hausswolff

Kenneth Anger’s Maldoror

Kenneth Anger, Topanga Canyon, Composite with Gustave Doré Engraving (1954) by Edmund Teske.

Les Chants de Maldoror, 1951–1952.

16mm; black and white; filmed in Paris and Deauville.

With a hand-held 16mm camera I shot my first series of short haiku. This was my apprenticeship in the marvels that surround us, waiting to be discovered, awake to knowledge and life and whose magical essence is revealed by selection. At 17, I composed my first long poem, a 15 minute suite of images, my black tanka: Fireworks.

I had seen this drama entirely on the screen of my dreams. This vision was uniquely amenable to the instrument that awaited it. With three lights, a black cloth as décor, the greatest economy of means and enormous inner concentration, Fireworks was made in three days.

An example of the direct transfer of a spontaneous inspiration, this film reveals the possibilities of automatic writing on the screen, of a new language that reveals thought; it allows the triumph of the dream.

The wholly intellectual belief of the “icy masters” of cinema in the supremacy of technique recalls, on the literary level, the analytical essays of a Poe or the methods of a Valéry, who said: “I only write to order. Poetry is an assignment.”

At the opposite pole to these creative systems there is the divine inspiration of a Rimbaud or a Lautréamont, prophets of thought. The cinema has explored the northern regions of impersonal stylization; it should now discover the southern regions of personal lyricism; it should have its prophets.

These prophets will restore faith in a “pure cinema” of sensual revelation. They will re-establish the primacy of the image. They will teach us the principles of their faith: that we participate before evaluating. We will give back to the dream its first state of veneration. We will recall primitive mysteries. The future of film is in the hands of the poet and his camera. Hidden away are the followers of a faith in “pure cinema.” even in this unlikely age. They make their modest “fireworks” in secret, showing them from time to time, they pass unnoticed in the glare of the “silver rain” of the commercial cinema. Maybe one of these sparks will liberate the cinema….

Angels exist. Nature provides “the inexhaustible flow of visions of beauty.” It is for the poet, with his personal vision, to “capture” them.

Kenneth Anger—Modesty and the Art of Film, Cahiers du Cinéma no. 5, September 1951

* * *

Little is known about Anger’s activities during the mid-1950s. By 1958 he still had not been able to complete any films in Paris. He held on to his hope of completing Maldoror. His stack of preproduction notes and sketches had grown larger and he had plans to photograph nudes in a graveyard. Several Parisian Surrealists threatened to hand Anger’s head to him if he shot Maldoror. The book’s fluid, dreamlike imagery had been one of the trailblazers of Surrealism, and his detractors felt that a gauche American with a reputation for pop iconography and bold homosexual statement would debase a sacred text.

Bill Landis—Anger: The Unauthorized Biography of Kenneth Anger, 1995

* * *

I discovered the book when I was quite young. I loved it, put a lot of passion into it. I found people to play the parts. I found settings, gaslit corners, places still had the romantic look of a Second Empire. It was a terrific ambition to make this epic film-poem. I found ways to translate the text’s extraordinary images. I planned to film a mid-nineteenth century story taking place in twentieth century Paris. I filmed “the hymn to the ocean” on the beach at Deauville, with Hightower and members of the Marquis de Cuevas Ballet. They danced in the sea; tables were placed beneath the water line so the dancers could stand on their points. It looked as though they were standing on waves. The people who called themselves “Surrealists” were furious—this group of punks threatened me—they didn’t want a Yank messing round with their sacred text. I just told them to go to hell! I also managed to film the war of the flies and pins. I put bags of pins and dozens of flies into a glass container; revolved the container and filmed in close-up. As the pins dropped the flies zigzagged to escape. In slow motion an impressive image.

Kenneth Anger—Into the Pleasure Dome: The Films of Kenneth Anger, edited by Jayne Pilling & Michael O’Pray, 1989

* * *

The sections of the film that were completed [are] stored in the Cinémathèque Française, but [their] exact whereabouts in the archive is unknown, with no images from the film being currently available for reproduction.

Alice L. Hutchinson—Kenneth Anger, 2004

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Donald Cammell and Kenneth Anger, 1972

• My Surfing Lucifer by Kenneth Anger

• Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome: The Eldorado Edition

• Brush of Baphomet by Kenneth Anger

• Anger Sees Red

• Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon

• Lucifer Rising posters

• Missoni by Kenneth Anger

• Anger in London

• Arabesque for Kenneth Anger by Marie Menken

• Edmund Teske

• Kenneth Anger on DVD again

• Mouse Heaven by Kenneth Anger

• The Man We Want to Hang by Kenneth Anger

• Relighting the Magick Lantern

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally

Švankmajer’s cats

Down to the Cellar.

“Black cats are our unconscious,” says Jan Švankmajer in an interview with Sarah Metcalf for Phosphor, the journal of the Leeds Surrealist Group. I’ve spent the past few weeks working my way through Švankmajer’s cinematic oeuvre where black cats were very much in evidence, although for a director who describes himself as a “militant Surrealist” there are fewer than you might imagine.

Jabberwocky.

The first feline appearance is in Jabberwocky (1973), a difficult film for animal-lovers when almost all the cat’s appearances seem to have involved throwing the unwilling animal into a wall of building blocks. Each “leap” that the cat makes through the wall interrupts the progress of an animated line being drawn through a maze; when the line finally escapes the maze, childhood is over. Our final view of the cat is of it struggling to escape the confines of a small cage: the unconscious tamed by adulthood.

Down to the Cellar.

The black cat in Down to the Cellar is not only the most prominent feline in all of Švankmajer’s films, it’s also carries the most symbolic weight in a drama replete with Freudian anxiety. The cat guards the entrance to the subterranean dark where its growth in size corresponds to the mounting fears of a small girl sent by a parent to collect potatoes.

Faust.

The cat seen at the beginning of Faust (1994) appears very briefly but nothing is accidental in Švankmajer’s cinema. Two separate shots show the cat in the window watching Faust on his way to meet Mephistopheles. As with Down to the Cellar, the cat oversees the threshold to another world, in this case the doorway to a labyrinthine building filled with malevolent puppets and the temptations they offer. The cat may also be the traditional symbol of ill fortune. Faust at this point in the story still has the option to turn back but he goes on to meet his fate. (I think there may also be another cat later in the film but I was too lazy to go searching for it. Sorry.)

Little Otik.

The cat that appears in the early scenes of Little Otik (2000) is a child substitute for a childless couple, its status reinforced by the scene of Bozena holding the animal like a baby. The arrival of the monstrous Otik usurps the cat’s position as the family favourite. Consequences ensue.

Švankmajer’s later features are catless. Insects (2018) is more concerned with arthropods and their human equivalents, while Surviving Life (2010) spends so much time inside the unconscious of its protagonist it doesn’t require a symbol. Lunacy (2005), on the other hand, is a combination of a story by Edgar Allan Poe—The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether—and the philosophical views of the Marquis de Sade. Švankmajer had already adapted two of Poe’s stories prior to this but The Black Cat wasn’t among them. Given the cruelties in Poe’s story and many of Svankmajer’s films, Lunacy in particular, this may be just as well.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Jan Švankmajer: The Animator of Prague

• Lynch dogs

• Jan Švankmajer, Director

• Don Juan, a film by Jan Švankmajer

• The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope

• Two sides of Liška