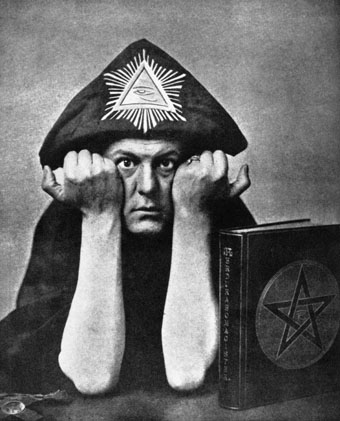

Aleister Crowley in 1912.

Back in 1999 I found myself making notes for a short essay on the subtle and often tenuous presence of Aleister Crowley in cinema. Despite Crowley’s reputation in the early years of the 20th century—famously labelled by tabloid hyperbole as “The Wickedest Man in the World”—he doesn’t seem to have ever been filmed. He does have a succession of cinematic avatars, however, in a variety of thrillers and horror films, usually manifesting in the guise of a fictional magus whose exploits will be based on the more lurid public perceptions of the Crowley persona.

After some research my short essay bloomed into a longer essay then began developing into a book-length project which I had the good sense to abandon. The idea still interests me but I didn’t have the time or resources to devote to all the detailed research such a project would require if it was going to be done thoroughly. It was also difficult at that time to see the some of the more obscure films, a crucial early example being Rex Ingram’s 1926 adaptation of The Magician, Somerset Maugham’s first novel whose central character, Oliver Haddo, is based on Crowley. The Magician has now been restored and reissued but at that time it was out of circulation entirely.

A Portuguese magazine ad.

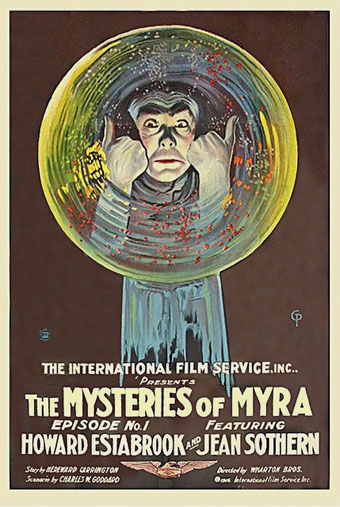

It’s also the case that there always seems to be more to find on this subject, a prime example being The Mysteries of Myra, a lost serial directed by Leopold & Theodore Wharton which has only now come to my attention. If the title seems vaguely familiar it’s because the screenwriter was one Charles W Goddard whose earlier The Perils of Pauline survives as a touchstone for silent melodrama if nothing else. The Mysteries of Myra dates from 1916, and is distinguished by being one of a number of films which received effects advice (and publicity, of course) from Harry Houdini. The Pulp Reader has a précis which includes this toothsome blurb:

BEWARE THE BLACK ORDER! So comes the warning from the spirit of Myra Maynard’s father, who reaches out to her from beyond the grave to warn her of danger from the masters of the occult arts that lurk in the shadows and mark her for murder on her eighteenth birthday. Only the world’s first psychic detective, Dr. Payson Alden, and his friend Haji the Brahman mystic, can save clairvoyant Myra from the terrors of The Grand Master of the Order, who tries to claim not only her fortune but her life by means of suicide-inducing spells, invasion of her chamber by spirit assassins, and even reanimation of the dead by a fire elemental.

A list of the episode titles reads like a track list for a metal album or a collection of Algernon Blackwood stories: ‘The Dagger of Dreams’, ‘The Poisoned Flower’, ‘The Mystic Mirrors’, ‘The Wheel of Spirit’, ‘The Fumes of Fear’, ‘The Hypnotic Clue’, ‘The Mystery Mind’, ‘The Nether World’, ‘Invisible Destroyer’, ‘Levitation’, ‘The Fire-Elemental’, ‘Elixir of Youth’, ‘Witchcraft’, ‘Suspended Animation’, ‘The Thought Monster’. The Black Order menacing the imperilled Myra (there’s always an imperilled woman in these things) is almost certainly based on Crowley and his acolytes. John Symonds’ biography The Great Beast contains an account of Crowley’s rituals published for appalled American readers in The World Magazine in 1914. That article, and the famous 1912 photo of The Master Therion gesturing in his ceremonial robes, was all the filmmakers would have required to create their villainous cabal.

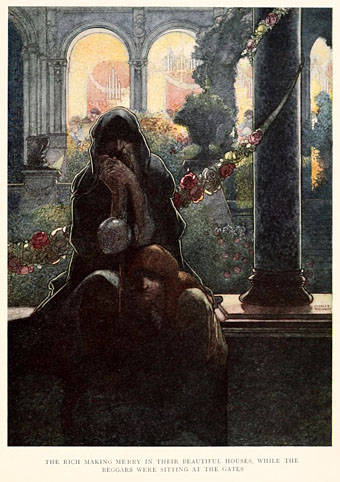

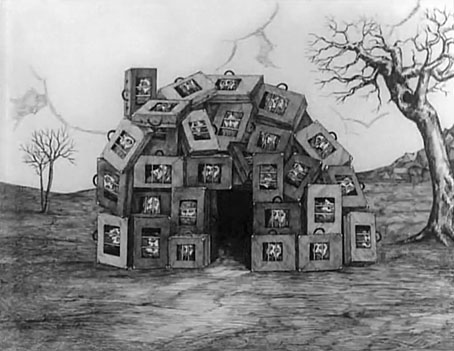

The Black Order at work.

The trouble with this kind of drama is that the description is often a lot more stimulating than the stodgy reality, so it may be for the best if Myra’s exploits have perished. Anyone eager to know more should avail themselves of the photonovel put together by the Serial Squadron using stills (some of which may be viewed here) and a novelisation of the serial story. The book is reviewed at Lovecraft is Missing. Unless anyone knows better, I’d say Aleister Crowley’s curious film career began with Myra’s mysteries.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Mask of Fu Manchu

• Aleister Crowley on vinyl