In an earlier post I mentioned how invaluable I’d found Philip Strick’s Science Fiction Movies, a large-format study published in 1976. Like Denis Gifford’s Pictorial History of Horror Movies (1973), the book was intended as a cheap introduction to a popular genre but Strick wasn’t content to limit himself to familiar titles, offering instead a remarkably eclectic list of films, many of which are barely science fictional at all: Last Year at Marienbad, The Saragossa Manuscript, The Hour of the Wolf, Teorema, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and so on. For my teenage self, and no doubt many other readers, this was my first encounter with these and other titles, and it was Strick’s descriptions that kept me on the lookout for them for many years (over 20 in the case of Saragossa). Strick’s equanimity treated cinema as a global medium, not one where Hollywood dominates the marketplace and all the conversation. Other films under discussion were definitely SF but unviewable to those of us who without access to an arts cinema, and little hope of ever seeing them on TV, European obscurities such as La Jetée, Fantastic Planet, Je t’aime, je t’aime and The End of August at the Hotel Ozone. Despite the book’s age, and the relative ease with which anyone can now see films such as these, a few scarcities remain, one of which I watched for the first time last week.

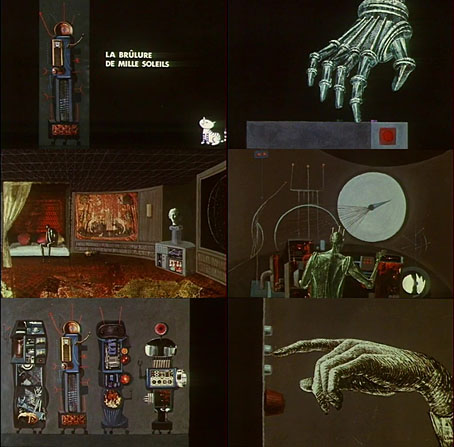

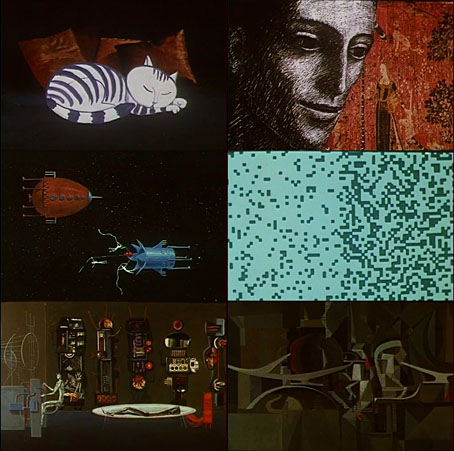

The Heat of a Thousand Suns/La Brûlure de Mille Soleils (1965) is a 25-minute animated film written and directed by Pierre Kast that Strick not only describes but further tantalises the reader with a pair of stills, which may account for its title having lodged in my memory all this time. Strick discusses the film between two other animations that are now very familiar: The Green Planet, an early work by Piotr Kamler, and Les Jeux des Anges by Walerian Borowczyk. (If all this sounds like wilful obscurantism on Strick’s part, on the previous page he discusses a pair of classic Hollywood features, This Island Earth and Forbidden Planet.) Kamler’s film is a humorous one, while Borowczyk’s is strange and disturbing; Kast’s film is pitched somewhere between the two:

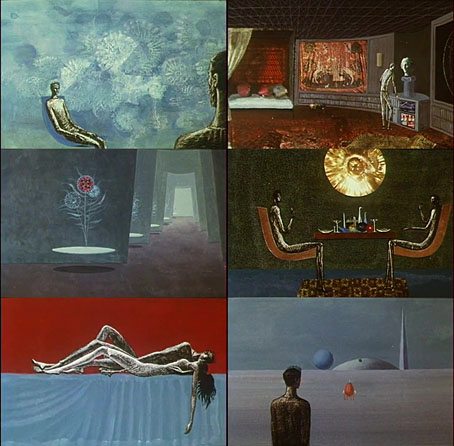

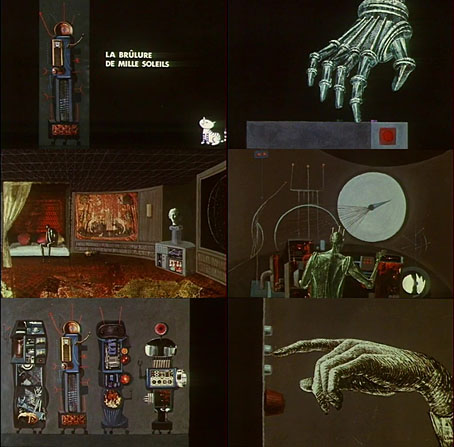

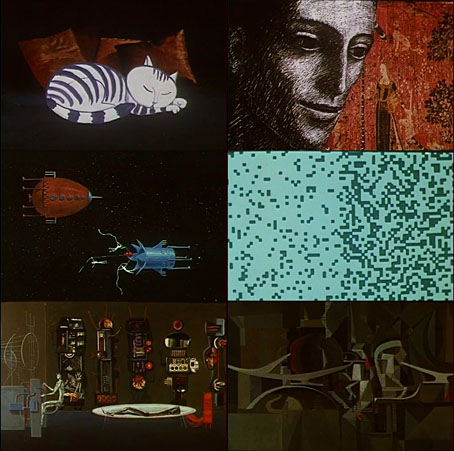

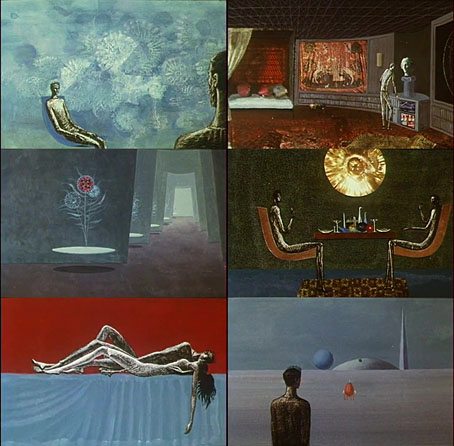

A young man in the far future becomes bored with the solar system he knows too well and goes for an unrepeatable trip to the stars, in the company of his robots and his cat. On a remote planet he encounters a tranquil civilization where something has only to be wished for, and it happens; he meets a girl, they fall in love, and their romance is frustrated by his complete inability to recognize the different standards of her society where sexual groups of eight comprise a family. Put together from paintings by a Spanish surrealist artist, Eduardo Luiz, whose suffused landscapes and delicate tapering figures provide the perfect balance to the gentle melancholy of the hero’s monologue, the film has the same touch of scorn at its centre as was evident in Kast’s other science-fiction works, Amour de Poche (1957) and Les Soleils de l’Ile de Pâques (1971), although its twinkling conclusion is more in keeping with his romantic comedy Vacances Portugaises (1961). It’s one of the most effective screen versions so far of science fiction’s crusade not so much for a better world as for better people on it.

Strick also mentions a detail about the production that I’d forgotten, namely the editing being the work of La Jetée director, Chris Marker. The latter’s credit makes the inclusion of a space-faring cat both funny and fitting although the animal is unconcerned by interstellar travel, and spends most of its time asleep. Another notable name is electronic composer Bernard Parmegiani who provided the score for this and other films by Kast; he also scored several shorts by Piotr Kamler and Borowczyk’s Jeux des Anges.

Now that I’ve finally seen Kast’s film I wouldn’t say it was worth the wait but it was definitely worth watching. The animation is very minimal, with most of the shots being still images that the camera wanders over. The SF scenario is very conventional, as are the trappings: a pointed rocket, bleeping robots, aliens that look and behave like Earth people even if they do have eight sexes. The film distinguishes itself much more with its design, the Giacometti-like figures, and the interior of the spacecraft which pre-empts Barbarella with its lavish chambers filled with period decor and artwork. Despite Strick’s praise, Kast’s conventionality seems a missed opportunity when animation can do so much more than ape live-action cinema. Piotr Kamler’s films, in particular Labyrinth (1969) and Chronopolis (1983), offer science-fiction scenarios that are remote from our own lives and preoccupations; so too with Borowczyk’s Jeux des Anges, a film whose industrial nightmare is closer to David Lynch than Barbarella. Kast does have a late surprise, however, although this may only mean anything to those familiar with Chris Marker’s photography.

The Heat of a Thousand Suns is on YouTube but with no subtitles for its French narration. The copy I watched was from this page which includes a subtitle file. I suspect this may be a DVD rip, and therefore immoral, but the same probably applies to the YouTube version as well. The choice is yours.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A Pictorial History of Horror Movies by Denis Gifford

• Saragossa Manuscript posters

• Marienbad hauntings

• Chronopolis by Piotr Kamler

• Les Jeux des Anges by Walerian Borowczyk