Penguin is really coming up with the goods these days, living up to their reputation as a house with high standards of cover design, unlike Picador and the shabby way they treated Cormac McCarthy recently.

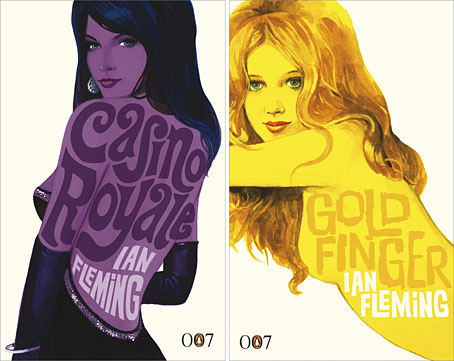

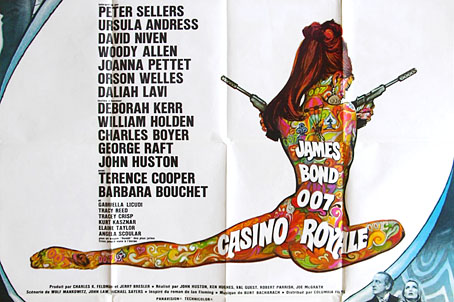

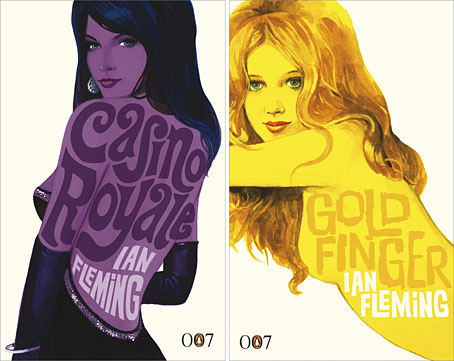

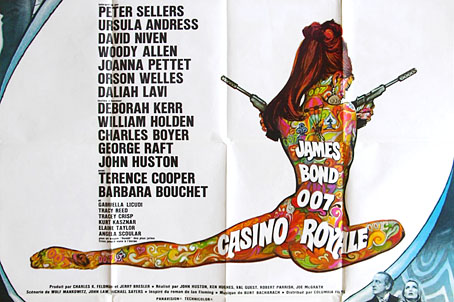

Ian Fleming’s Bond novels are the latest to receive a makeover with some fabulous art from illustrator Michael Gillette. 2008 is Fleming’s centenary so the books have been republished as demi-format hardbacks with these new designs adorning the jackets. Each cover features a different girl matched to the theme of the book (yes, I know they’re women but in Bond’s world women are always girls unless they’re Miss Moneypenny); each cover also features groovy period type which alludes to the hand-drawn elaborations of the Sixties and Seventies. The effect is reminiscent of the poster art for the 1967 film of Casino Royale (below) which used a naked girl as the focal point; all Bond posters before and after this place oo7 himself centre stage. Penguin even dare to push the level of pastiche by making On Her Majesty’s Secret Service look rather like an old romance novel, not such a surprising decision since this is the book where Bond gets married.

My favourite Bond covers remain the old Pan paperbacks from 1963 but that’s just me; these look great. There’s been a persistent moan recently from authors and publishers worrying about file sharing as they foresee the publishing world going the same way as the music business. The solution is obvious: you can’t stop texts being copied and distributed but you can make the books themselves desirable objects so make them worth buying and owning. Penguin has numbered the spines of the new Bond books as they did with their recent Sherlock Holmes reprints, a smart appeal to book collectors as well as a tip to read them in the order they were written. “Smart” is the key word here; Picador take note.

Update: The Pan covers mentioned above were designed by Raymond Hawkey. Bond site MI6.co.uk has some details about the designer.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Repackaging Cormac

• The World’s Greatest Detective

• James Bond postage stamps

• Boys Own Books