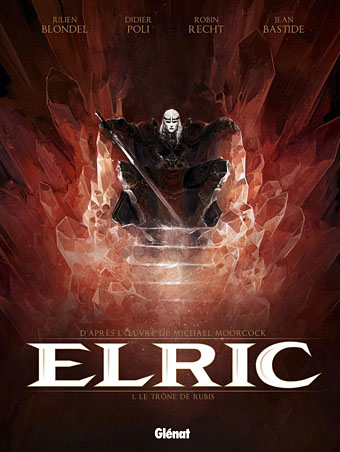

The closest I ever got to illustrating Michael Moorcock’s Elric character was the sleeve for The Chronicle of the Black Sword in 1985, a Hawkwind concept album based on the first couple of Elric books. That design favoured a decorative approach over anything illustrative, however. At the time I felt too intimidated by the renderings of Elric’s first illustrator, James Cawthorn, and subsequent depictions by book cover artists such as Michael Whelan, to attempt my own version of the character. These days I pay little attention to heroic fantasy of any kind but I do look out for new depictions of Moorcock’s anti-hero. Earlier this year the French bande dessinée publisher, Glénat, released the first album in a planned series of five comic-strip adaptations of the Elric books. Many creditable Elric comics have appeared since the 1970s, not least the Cawthorn version of Stormbringer, one of the earliest and best, and Philippe Druillet’s own somewhat eccentric production. Mike Moorcock very generously sent me a copy of the Glénat volume this week, and I’d say this is now the one to beat.

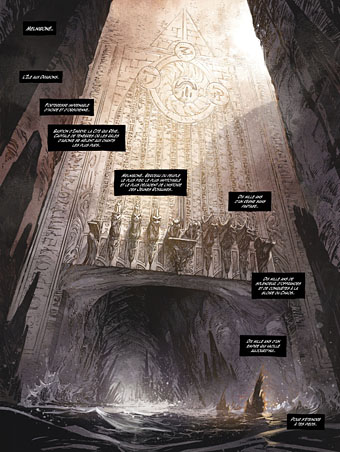

Writer Julien Blondel has adapted the books with the art duties being taken by Didier Poli and Robin Recht. Jean Bastide is the colourist. I’ve always preferred the French and Belgian approach to comic art over the American style so I’m naturally biased towards a book such as this. That said, the art is marvellous, and so many of the details feel just right. Moorcock portrays the Melnibonéans as decadent and cruel, something that Poli and Recht portray with scenes of naked slaves being bled, butchered, and even used as human torches for the blithe amusement of their masters. The general atmosphere in the opening pages is like something from Flaubert’s Salammbô with its combination of antique depravity and the massing of great armies prior to battle. They don’t slouch with the monstrosities, either, there’s a spot of Lovecraftian weirdness when Elric is rescued by Straasha, the Sea King. I look forward to seeing how they deal with Arioch (who puts in an appearance at the end) and the other Chaos Lords. The dialogue is all in French, of course, but if you know the books it’s easy to follow even with French as limited as mine.

The Glénat site has a few more page samples. Moorcock has been watching these books being adapated and re-adapted for decades, and he says this is among the very best. For anyone with more than a passing interest in the brooding albino prince it’s well worth seeking out.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Salammbô illustrated

• Jim Cawthorn, 1929–2008