More Lovecraft book covers. Blame the season for this although depictions of Lovecraft’s cosmos have been occupying my thoughts for a while now, as I explain below.

A couple of years ago I wrote about the weird-fiction collections that Mnémos had been publishing in France, all of which used for their cover art paintings by the Polish “anti-symbolist” Zdzislaw Beksinski. I like Beksinski’s paintings very much, and thought they were a good match for most of the covers that Mnémos had produced, being sufficiently weird and evocative without being directly illustrative. (The sole exception was the peculiar dog-like creature on the cover of a Frank Belknap Long collection, The Hounds of Tindalos. Long’s “hounds” are malevolent extra-dimensional entities whose name shouldn’t be taken literally.) I mentioned that Mnémos had also announced a seven-volume collection of HP Lovecraft’s fiction and non-fiction, but at the time of writing there were no pictures of the books available, and I’d forgotten all about the collection until a few days ago. All the books in the set, which are translated by David Camus, have since been reprinted as standalone volumes.

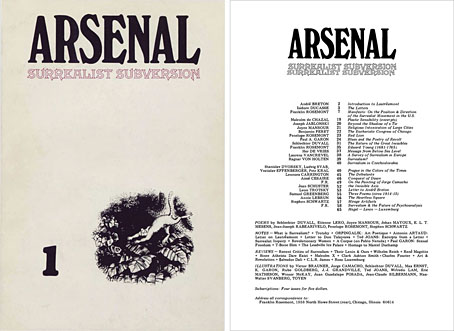

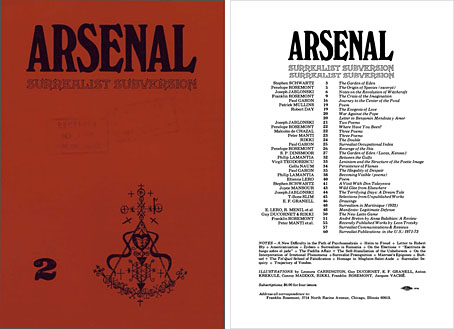

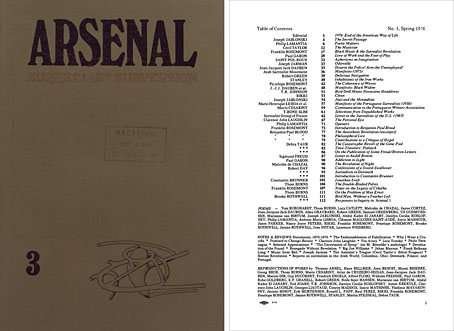

Intégrale Howard Phillips Lovecraft is a little deceptive as a title for a Lovecraft collection when the word “intégrale” is often applied to complete editions of something. The Mnémos set looks like it contains all of the fiction in the first few volumes plus a quantity of essays, but Lovecraft famously wrote more letters than he did stories; the letters here are a small selection inside volume 6. In addition to the books, the collection also contains a map of the Dreamlands, together with cards and bookmarks embellished with details from Beksinski’s paintings.

As with the Mnémos covers for Frank Belknap Long and Clark Ashton Smith, you could use many different Beksinski paintings for these editions, all of which would work to some degree. Even if some of them seem mismatched they offer a change of direction away from those varieties of fantasy art which have become very mannered in recent years when applied to weird fiction in general and Lovecraft’s stories in particular. This is partly a result of over-production: the huge success of the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game drove a demand for more and more Lovecraftian artwork, with the result that clichés emerged sooner than they would have done if the available imagery was limited to book illustrations and comic strips. I’ve contributed to the situation as much as most although I’ve also kept trying to find directions away from the stereotypes; my Cthulhoid picture was one such attempt even it still leans on the tentacular. I’ve been thinking recently of following the King in Yellow portrait with more poster-size art that explores other possibilities in this area. I’d encourage other artists to do the same when they can (commercial constraints often force your hand). Beksinski’s paintings show one route out of the mannerist cul-de-sac.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The fantastic art archive

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Beksinski on film

• Beksinski at Mnémos