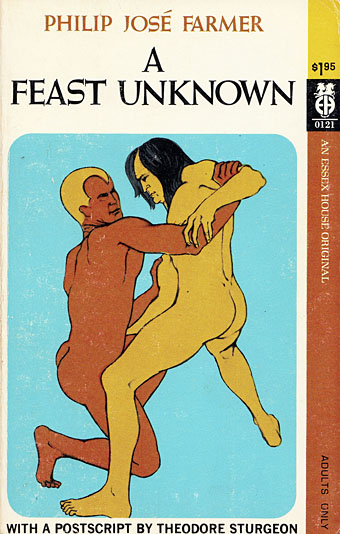

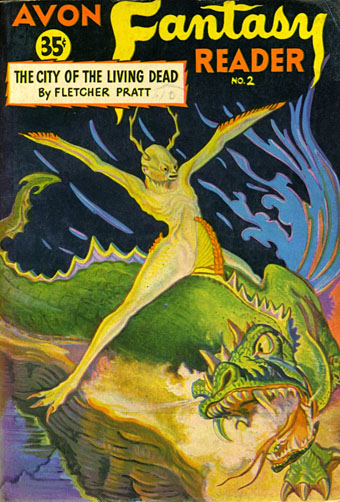

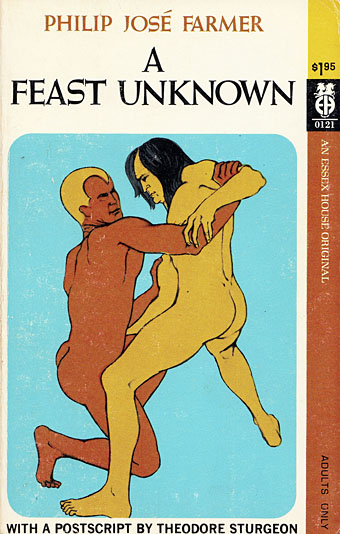

I’ve known the name of American publisher Essex House for many years but the books they published, all of which appeared in a frenzy of activity from 1968 to 1969, have never been easy to find in the UK. The company is chiefly of note today for having three original Philip José Farmer novels on their list, all works of fantasy with the erotic side more dominant than in Farmer’s previous work. Erotic fiction with a generic slant was the Essex House speciality, and while the Farmer covers have appeared here before, I’d not seen any other Essex House covers until the discovery of this page which collects 38 of the 42 published titles.

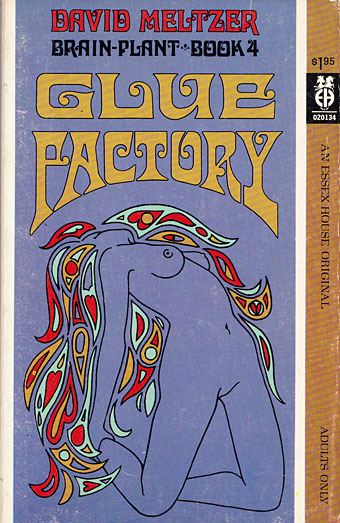

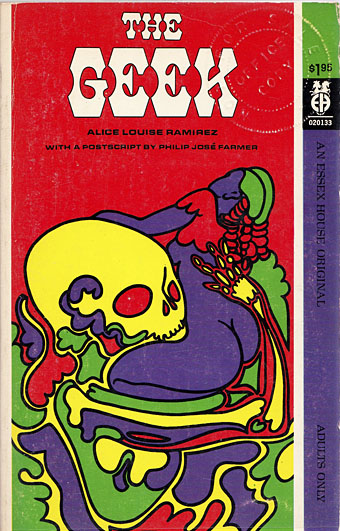

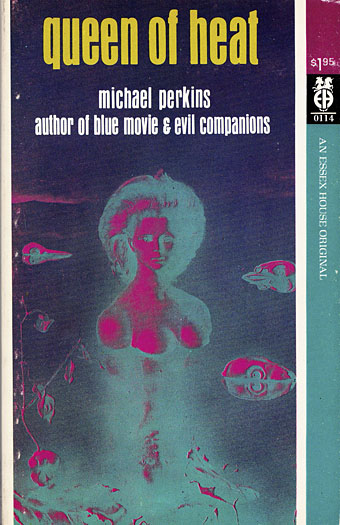

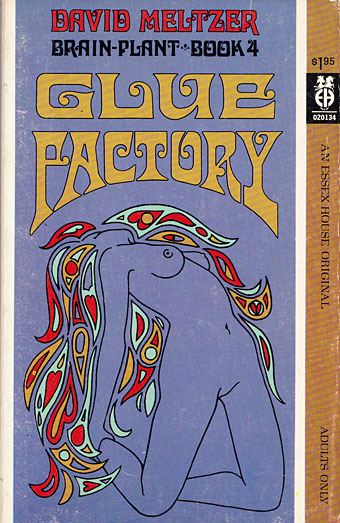

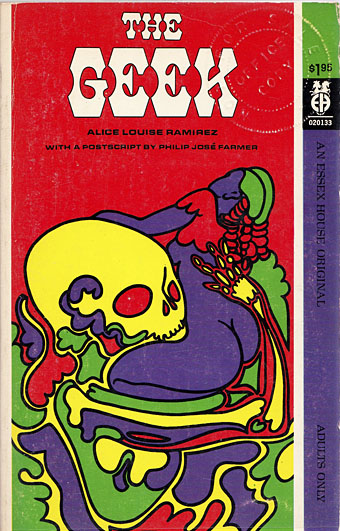

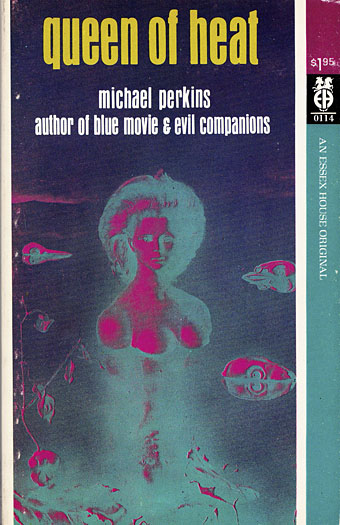

It’s immediately evident looking down the list that the (uncredited) designer managed to forge a distinctive identity for the books at a time when any cover would suffice if the written material was sufficiently pornographic. Many of the covers borrow (or mutate) pre-existing artworks, while others emulate the watered-down psychedelic style that by the late 60s was visible everywhere in the US and much of Europe. These aren’t all great pieces of design but the graphics on erotic titles in the 60s either played safe by favouring text-only covers or sported technically crude emulations of paperback illustration. (For an example of just how technically crude, see this post about some of the many gay pulps on sale in the US.)

Essex House may not have been around for long but they seemed to be attempting something different, at least where the covers were concerned. I’ve only read the Farmer books so I can’t vouch for the other titles but the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction writes that

…about half the 42 titles published by Essex House were sf/fantasy; they included novels by Philip José Farmer, Richard E Geis, David Meltzer (perhaps the most distinguished), Michael Perkins and Hank Stine…of which a number were ambitious, some literary, and most somewhat joyless—even emetic—and redolent of 1960s radicalism.

Pornography as a tool of radical politics had a brief vogue in the late 60s and early 70s, something that’s particularly evident in the underground magazines of the period. The results may be “joyless” to some but then I find a lot of the alleged classics of science fiction joyless so it’s all a matter of taste. There was no equivalent of Essex House in the UK but in the 1970s France had the Chute Libre imprint which not only published all of the Essex House Farmer titles but did so with a collection of equally striking (or “joyless”) cover designs.

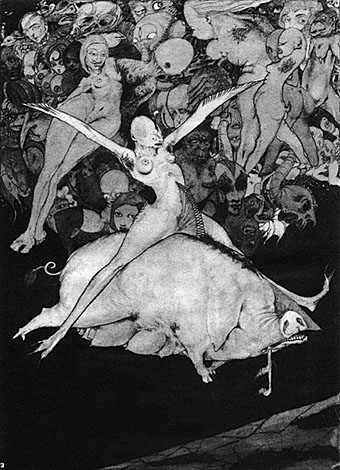

Artwork is a solarised version of Le Bout du monde (1949) by Leonor Fini.

Continue reading “Essex House book covers”