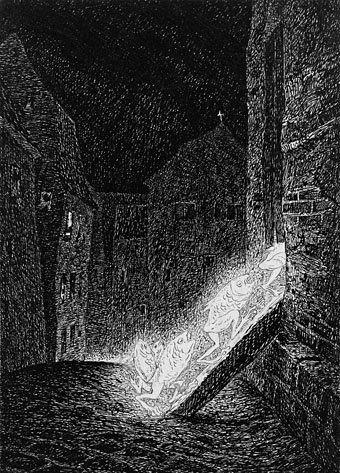

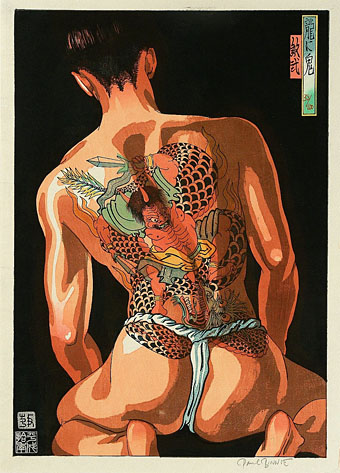

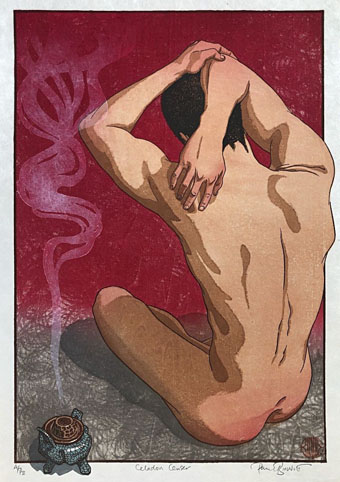

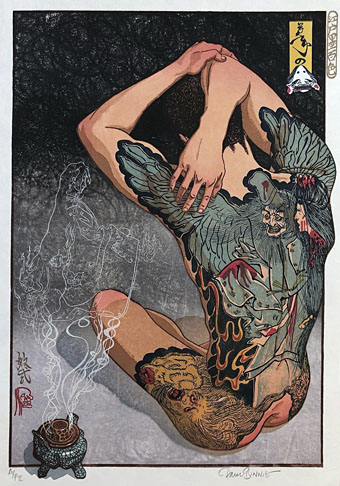

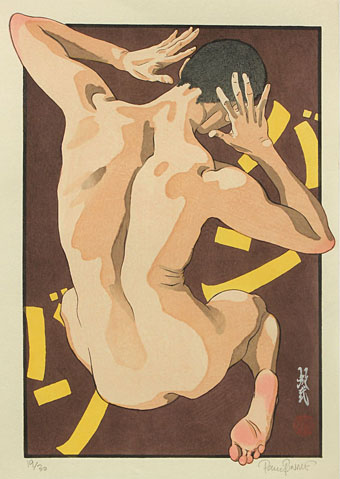

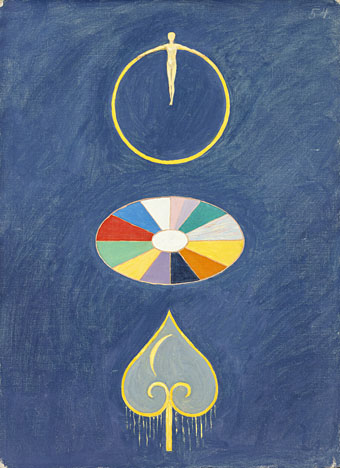

No. 54 (1915) by Anna Cassel.

• “I called it the treasure hunt: two years of tapes appearing from closets, letters dropping out of attics, persuading a film company to find the rushes of a TV show buried in a warehouse, paying a film director to digitise unused footage and a radio company to surface an old broadcast.” Nick Soulsby on pursuing the ghosts of Coil for his book about the group, Everything Keeps Dissolving.

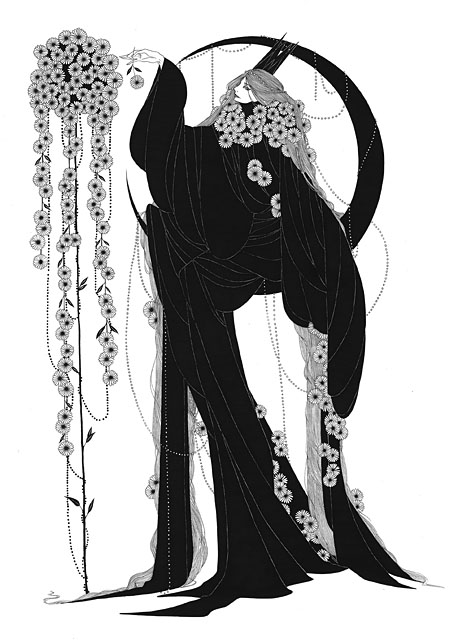

• “It is likely that af Klint scholarship is on the brink of some radical changes regarding attribution and authorship.” Susan L. Aberth on the researches revealing collaborations between Hilma af Klint and other mystically-inclined women artists. It makes a change reading something about this group that isn’t completely dismissive about the beliefs that informed their work.

• New music: No Highs by Tim Hecker (“a beacon of unease against the deluge of false positive corporate ambient currently in vogue…”), and Seascape–polyptych by Jan Jelinek.

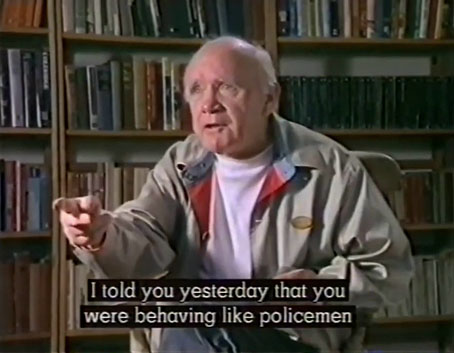

I think an unfortunate effect of Foucault’s work, as it was absorbed by academia, was that it made historians reluctant to call people or sexual acts in the past ‘homosexual’ or ‘gay’ since these terms ‘did not exist at the time’ or were recent creations. This gave some homophobes a spurious defence when suggestions were made as to the inclinations of their heroes, but it also—or so I thought—tended to downplay the reality of non-opportunistic homosexual desire as a constant in history, reducing it to recorded acts performed and then deeming these inadequate evidence anyhow, because they were assumed to have taken place in a fuzzy sexual universe.

If, as it seems to me, and as it seemed to Symonds and Carpenter, terms like ‘homosexual’ were invented in the effort to describe a type of person that has always existed, then they are in essence just a shorthand. Each term has its history, associations and effects, but—and perhaps this makes me an unsophisticated thinker—I think it’s the sexual feelings that fundamentally matter, and that these have existed across time. For that reason, I don’t find the Victorian sexual psyche, as far as it can be defined, alien or outlandish, or hard to speculate on. It is the product of sexual feeling filtered through observable social beliefs and conditions.

Tom Crewe talking to Amia Srinivasan about The New Life, Crewe’s debut novel which explores Victorian sex and sexuality

• “I’ve been tumbling down the rabbit-hole of toy theatre all my life, and I’m tumbling still.” Clive Hicks-Jenkins on the dark art of the toy theatre.

• At Public Domain Review: Jean Baptiste Vérany’s Chromolithographs of Cephalopods (1851).

• “Glass is perhaps the most frequently overlooked material in history,” says Katy Kelleher.

• At Cartoon Brew: Chris Robinson remembers the surreal animations of Run Wrake.

• At Unquiet Things: Of Dreams and Dark Pasts: Surrealist Painter Sofía Bassi.

• RIP Harry Belafonte.

• House Of Glass (1969) by The Glass Family | Heart Of Glass (1978) by Blondie | Slow Glass (1997) by Paul Schütze