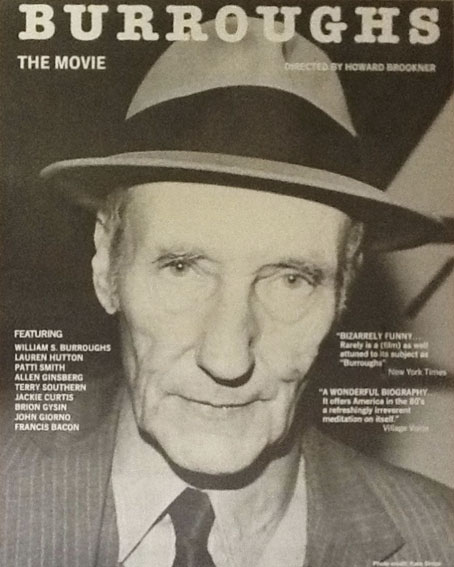

Photo by Kate Simon.

Howard Brookner’s 86-minute documentary Burroughs: The Movie (1983) has been mentioned here on several occasions, and with good reason since it’s the best film anyone has made or will make about William Burroughs and the Beat circle he emerged from in the 1950s. Brookner’s documentary is a model film biography, opening with the writer’s appearance on Saturday Night Live in 1981 then backtracking to his childhood in St. Louis, his family life, the Beat period, the Bunker years, and so on, ending with his move to Lawrence, Kansas in the early 1980s. It’s intimate, frequently very funny, and reveals a human side to Burroughs too often buried by the weight of a sinister reputation. Brookner spent several years working on the film which features appearances from, and interviews with, a priceless range of friends, relatives and collaborators: Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Hunke, John Giorno, James Grauerholz, Brion Gysin, Patti Smith, Terry Southern, Mortimer Burroughs (William’s brother), William S. Burroughs Jr (William’s son who died while the film was in production), Francis Bacon, Jackie Curtis and many others. Tom DiCillo and Jim Jarmusch helped with the camera and sound duties.

The BBC screened the film as part of their Arena arts strand during the miraculous run of that series in the 1980s, since when it’s become difficult to see unless you have a copy on tape. So it’s been good to hear that Aaron Brookner is intending on restoring and reissuing his uncle’s debut film, having found the original print along with many outtakes. Howard Brookner died of AIDS in 1989 so Aaron is launching a Kickstarter fund to restore the film today, December 1st, which is World AIDS Day:

Burroughs: The Movie is a very special film: with in-depth interviews from Allen Ginsberg, Brion Gysin, and many more; intimate scenes such as Burroughs and James Grauerholz with Burroughs’ son Billy Jr.; and it is the only time on camera Burroughs speaks candidly about the tragic shooting accident that left his wife Joan dead. As Janet Maslin wrote in The New York Times Review: “Rarely is a documentary as well attuned to its subject as Howard Brookner’s Burroughs, which captures as much about the life, work and sensibility of its subject as its 86 minute format allows. Part of the film’s comprehensiveness is attributable to William S. Burroughs’ cooperation, since the author was willing to visit old haunts, read from his works and even playfully act out a passage from Naked Lunch for the benefit of the camera. But the quality of discovery about Burroughs is very much the director’s doing, and Mr. Brookner demonstrates an unusual degree of liveliness and curiosity in exploring his subject”. (more)

Given that so many of the film’s participants are now dead this project has historical as well as aesthetic significance. If you have some spare cash and a more than passing interest in William Burroughs than I’d urge you to lend your support.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The William Burroughs archive