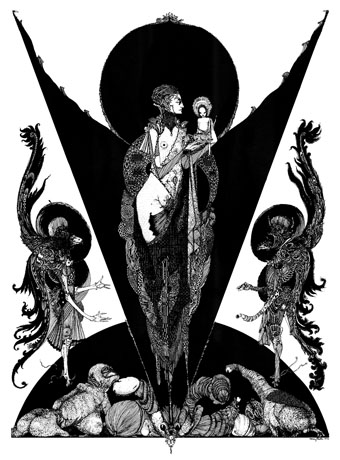

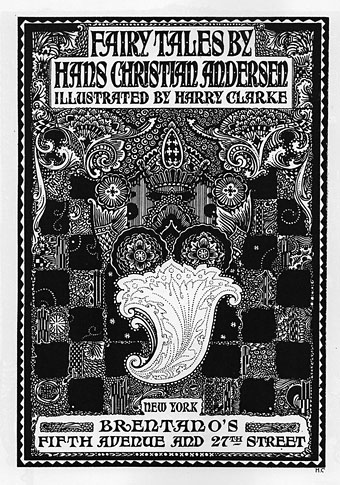

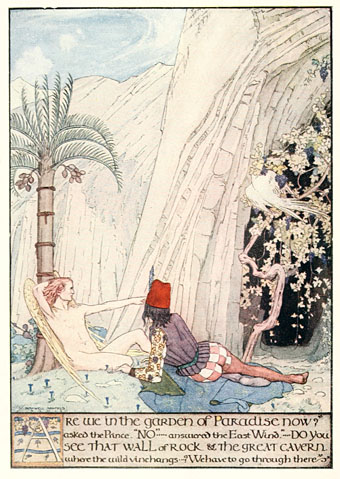

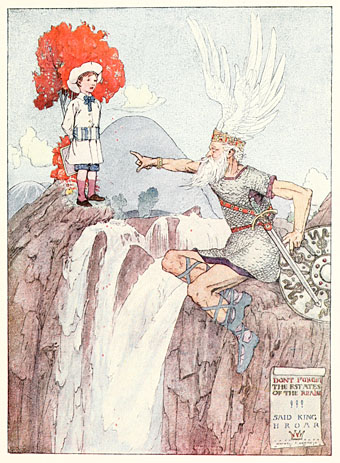

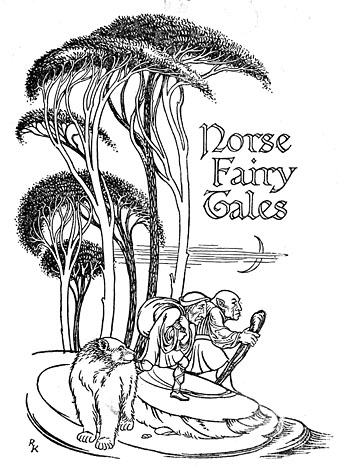

More tales from the northern lands, and a book illustrated by two people this time. The Knowles were a pair of brothers, Reginald Lionel (1879–1954) and Horace John (1884–1954), who produced several illustrated editions together while also working independently. Sibling illustrators are unusual but not unprecedented; the Knowles’ contemporaries included the Robinson brothers—Charles, William (Heath) and Thomas—who worked together on an edition of Hans Christian Andersen’s stories. Norse Fairy Tales (1910) is a collection of folk stories that overlap in places with the more familiar tales from Denmark and Germany. The book was compiled by FJ Simmons from Norwegian collections by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe which had been translated into English by George Webbe Dasent. Simmons says in his introduction that he edited (or bowdlerised) his selection a little in order to make some of the pieces suitable for a young readership although he doesn’t give any details. His book is one I ought to have gone looking for sooner after I swiped part of a related illustration for a CD design some time ago. A drawing by Reginald Knowles of a troll walking among trees appears in a source book of Art Nouveau graphics which I’ve borrowed from for many years. Reginald’s trees proved to be perfect for the CD. This was a lazy move on my part but I’d been asked to rescue a design which wasn’t working, and the deadline was a tight one.

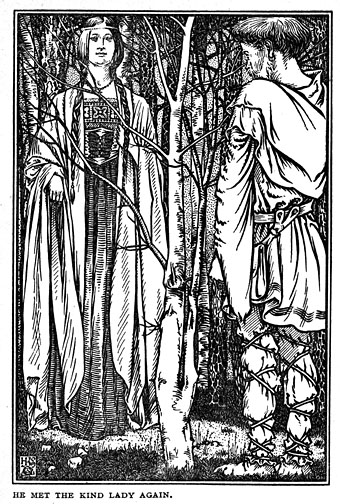

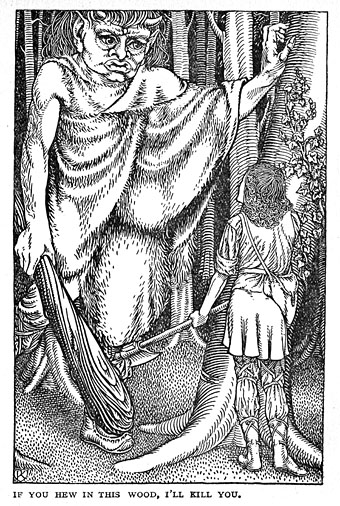

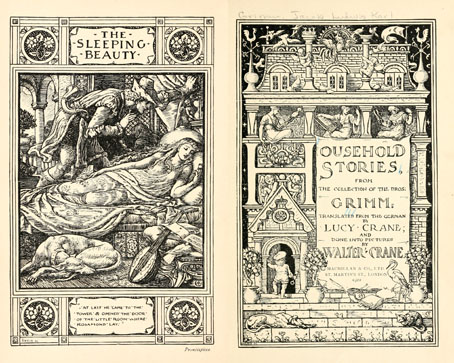

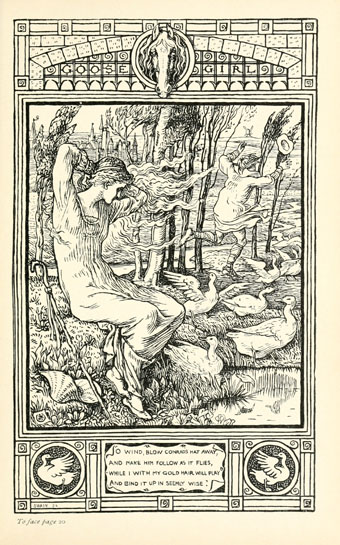

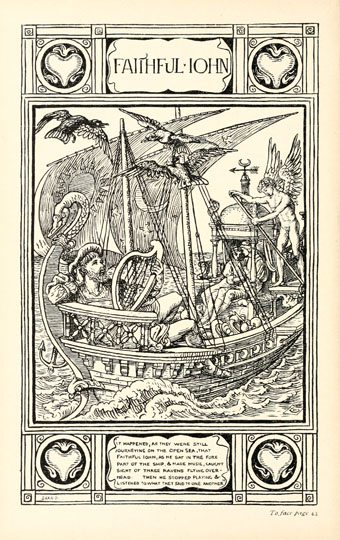

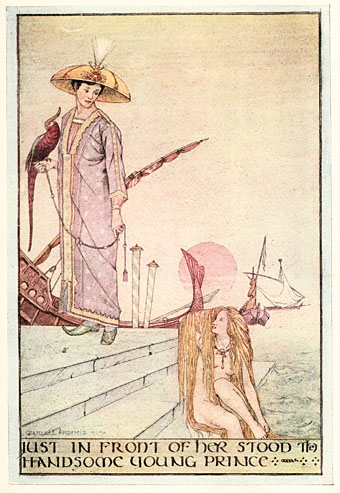

Simmons may have trimmed some of the texts but Norse Fairy Tales still runs to 55 stories that fill 500 pages for which the Knowles’ provide full-page illustrations, a few colour plates and many smaller drawings. Each artist is identifiable by their initials. All the black-and-white art is pen-and-ink but Horace’s drawings imitate the style of early wood engravings, a look that works well with the material, while Reginald’s drawings would be identifiable even without his initials since his work tends to be a little more stylised, as with the sinuous trees that I borrowed. This is an impressive book that might be better known if there wasn’t such a profusion of illustrated Brothers Grimm and Hans Andersen collections. Find out what the trolls are getting up to here.

(Note: the Internet Archive scan has excessively browned pages. All the images here have been run through filters to remove the colouration.)