Harry Clarke’s work appeared in the pages of The Studio magazine on several occasions, either in review or as here, a subject of a special feature. I linked to a later piece a few years ago but until this week I hadn’t seen this earlier entry from November 1919. (I keep intending to download all the issues at the University of Heidelberg and go through them properly. One day…)

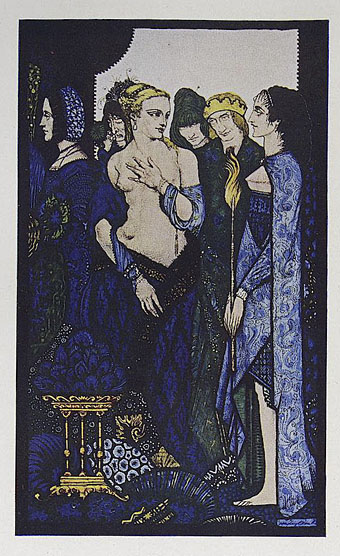

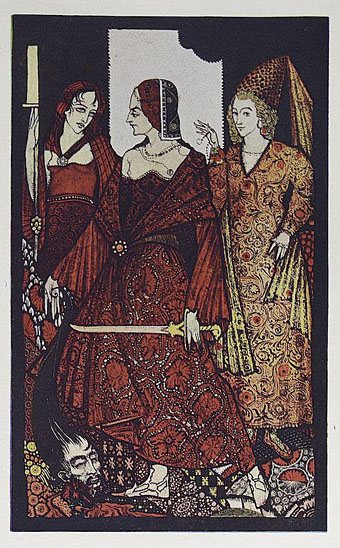

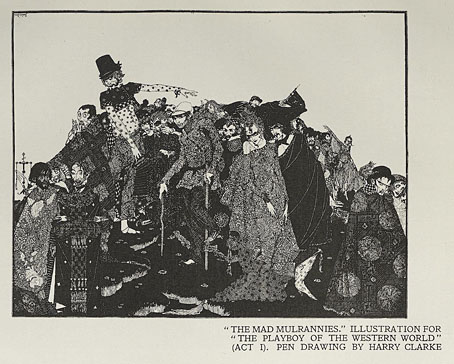

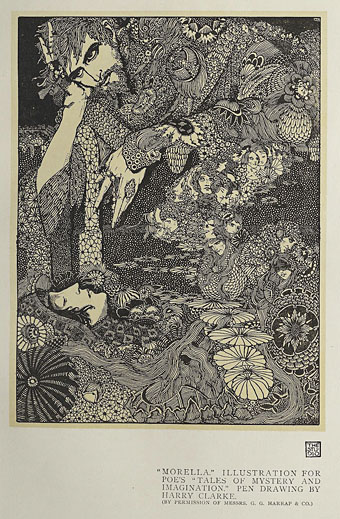

Thomas Bodkin was a barrister and director of Ireland’s National Gallery who became a great champion of Harry Clarke’s work. Like many of the artist’s Irish enthusiasts, Bodkin was familiar with Clarke’s stained-glass designs which he highlights here. Clarke’s stained-glass art is as important a part of his career as his illustration—it was the family business, for which he created over 160 windows and panel designs—but the fruits of this work were seldom seen in print. The Studio was in the vanguard of print reproduction at the time, especially where colour was concerned, so the reproductions of the glass designs are especially good, much better than some of the colour plates in Clarke’s illustrated books. The ever-popular illustration for Poe’s Morella also benefits from reproduction on a large page where the minuscule faces hiding in the decoration become more apparent.

A few pages before the Clarke feature there are two works by John Hancock that I hadn’t seen before. Hancock and Clarke were both featured in The Golden Hind, the arts magazine edited by Clifford Bax and Austin Spare, but Hancock lapsed into almost total obscurity following his death at the age of 22. For years all I knew of either him or his work was a book reproduction of the Golden Hind piece together with a note saying that he was dismayed by his declining health, and that his body was found floating in Regent’s Canal. (See this page for more.) Harry Clarke also suffered from poor health for much of his life, and died at the age of 41 in Chur, Switzerland, a town best known today for being the birthplace of HR Giger. Some of the phallic monstrosities lurking at the margins of Clarke’s Faust drawings might be precursors of Giger’s airbrushed abominations. I wonder if Giger knew of this connection? Answers on a biomechanical postcard.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Harry Clarke: His Graphic Art

• Harry Clarke and others in The Studio

• Harry Clarke’s Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault

• Harry Clarke in colour

• The Tinderbox

• Harry Clarke and the Elixir of Life

• Cardwell Higgins versus Harry Clarke

• Modern book illustrators, 1914

• Illustrating Poe #3: Harry Clarke

• Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke

• Harry Clarke’s stained glass

• Harry Clarke’s The Year’s at the Spring

• The art of Harry Clarke, 1889–1931

I love anything and everything Harry Clark, especially his glass work. Same for Kay Neilson. Even as a child I was drawn to Clark’s work. (pun sadly intended)

I purchased a large 1920 leather bound Poe/Clark book back in September for a healthy price (gulp) -but I had to get it as I’d never seen one in a quartro size. I love it because it looks like a big black stuffy family bible. Strangely , I can’t seem to find another copy anyplace, even on Abebooks and the like.

Anyways, as always, thanks for sharing these great links. Your site is such great fun-and a much needed distraction from the madness just outside the door.

Thanks, I’ve been enjoying giving this place more of my attention, and enjoyment always has to be a major factor. There seems to be a general return to the blog format just now, even though it never went away for determined users like myself. Lots of journalists migrating to Substack in the hope of cultivating a paying audience for their writings. This place allows me to do something I’ve been doing my whole life, pointing the way to things I like that other people might be interested in.

I managed somehow to miss Harry Clarke’s work until I was in my mid-20s despite having seen a couple of his drawings in books. I’m lucky to have a battered first edition of his illustrated Swinburne which I got for a mere £10, only to discover that a couple of the drawings had been removed (a common problem with illustrated books). Even in butchered form it’s still good to have since the drawings are among those that you don’t see as often as his more popular works. Meanwhile I have four copies of his illustrated Poe, none of which are completely satisfactory when it comes to reproduction. I’ll probably be buying it again at some point.