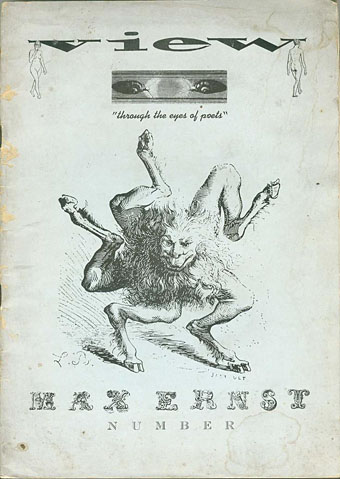

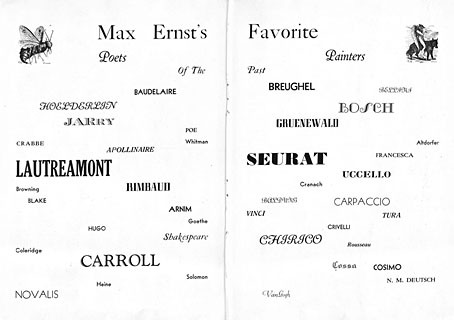

If you hadn’t noticed by now, this year is the centennial anniversary of the publication of Ulysses and The Waste Land. It’s also a centenary year for the Surrealist movement although the same could be said of last year and the next couple of years when Surrealism, like most art movements, doesn’t have a definite point of departure. Apollinaire first coined the term in 1917, after which it became attached by a process of accretion to some of the moves being made in the wake of Dada. André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s collection of automatic writing, The Magnetic Fields, was published in 1920 but it would be another four years before the appearance of the first Surrealist manifesto, and there were two of those produced by rival groups within a few weeks of each other as a result of the childish factionalism that plagued the movement from the outset.

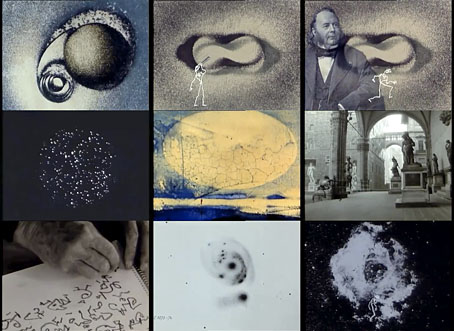

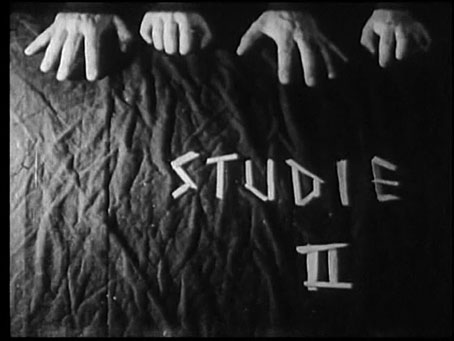

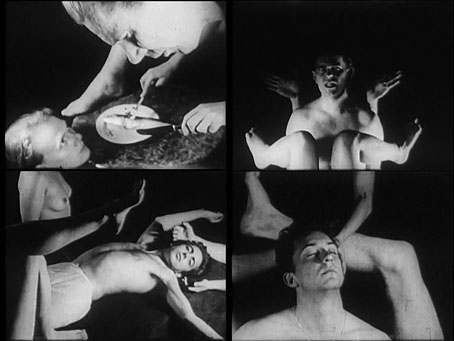

Anyway, Study II (Hallucinations) (1952) is a short film that can be regarded as Surrealist even if it wasn’t intended as such. I didn’t know playwright Peter Weiss had made any films but then I only really know him at all from his extraordinary Marat/Sade. Study II is a long way from Marat/Sade in both form and content, being an attempt to capture the fleeting impressions that enter the mind before the onset of sleep. The juxtaposition of naked figures and isolated body parts is reminiscent of many Surrealist paintings or collages, although filmed tableaux such as these are seldom as effective as still images or animated ones when there’s always the distracting awareness of watching people holding an awkward pose. But Weiss’s film would suit a screening with similar Surrealist shorts, especially Eric Duvivier’s La femme cent têtes, another display of awkward poses and hallucinatory moments.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Marat/Sade