I should have mentioned this a lot sooner considering the museum sent me a copy of the exhibition prospectus. Maison d’Ailleurs is the Museum of Science Fiction, Utopia and Extraordinary Journeys in Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland, and their current exhibition is Lines of Flight—Mervyn Peake, the Illustrated Work. Yverdon-les-Bains is too out of the way for most of us but the event gives me another excuse to draw attention to Peake’s illustrations for Lewis Carroll; some of the drawings from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass and The Hunting of the Snark are among the works on display until February 14, 2010.

Mervyn Peake (1911–1968) is celebrated today as the writer of the extraordinary series of novels about Titus Groan (often referred to as the Gormenghast books). Yet, during his lifetime he was more known for his graphic work.

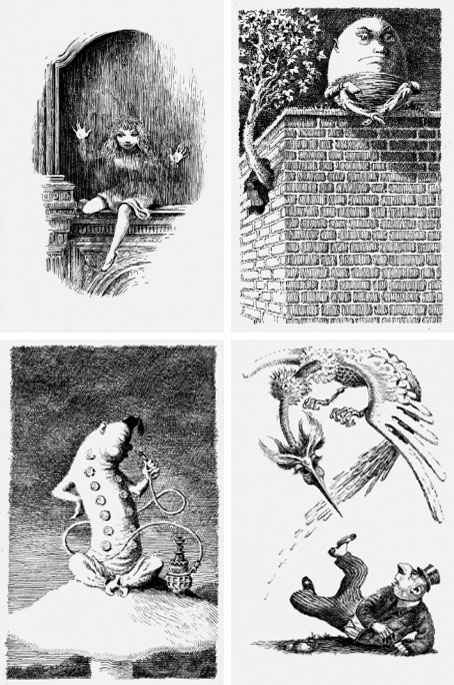

From 1939 and for almost two decades, Peake produced illustrations both for his own work (Captain Slaughterboard; Rhymes without Reason) and for classics (Household Tales by the brothers Grimm; Alice in Wonderland; Treasure Island). His mastery of the pen and the pencil were unrivalled. Visually, his style could be disarmingly economical, using very pure and clean single lines to create a striking sense of volume. But with cross-hatching and dots Peake could also make his drawings look like engravings, providing the characters and objects he depicted, or the background to them, with rich and varied textures and a wide range of shades. (More.)

For more of Peake’s illustration work, see Mervynpeake.org.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

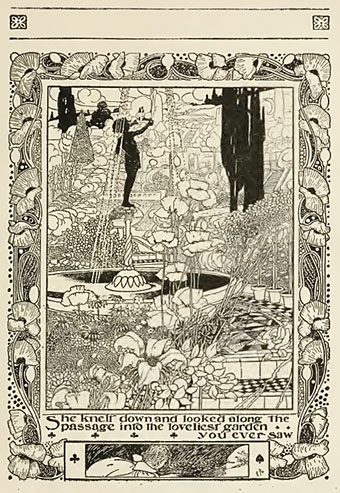

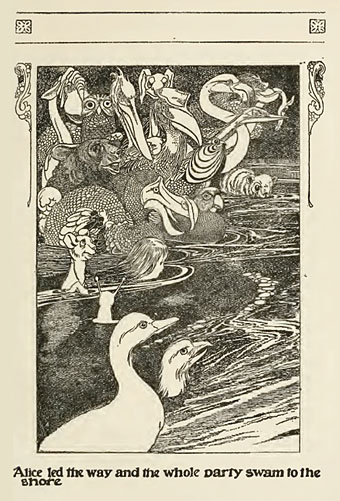

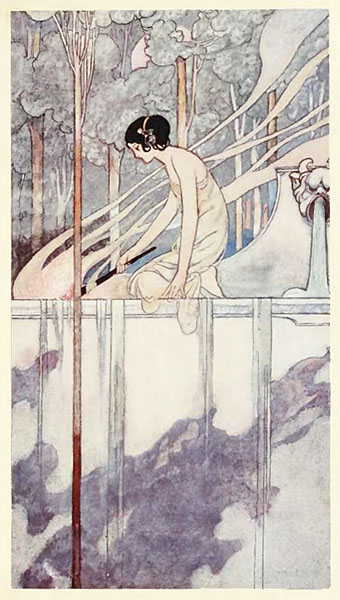

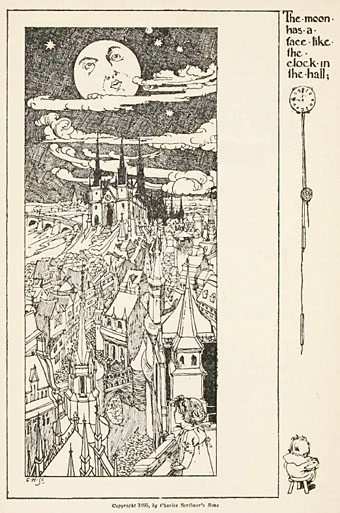

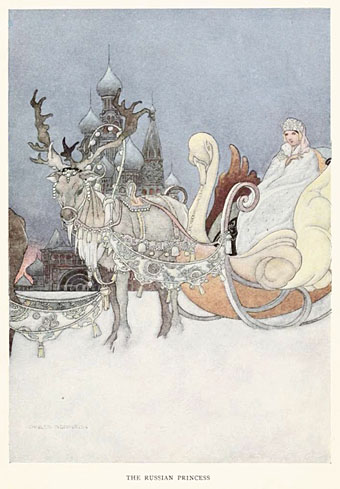

• Charles Robinson’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

• Humpty Dumpty variations

• Alice in Wonderland by Jonathan Miller

• The art of Charles Robinson, 1870–1937

• Lovecraftian horror at Maison d’Ailleurs

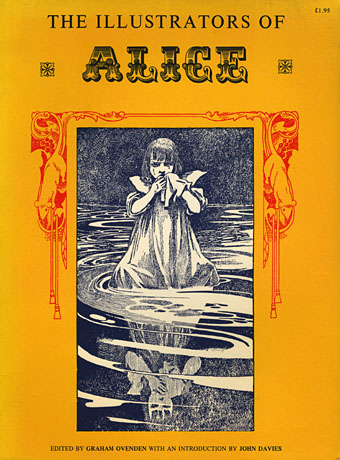

• The Illustrators of Alice