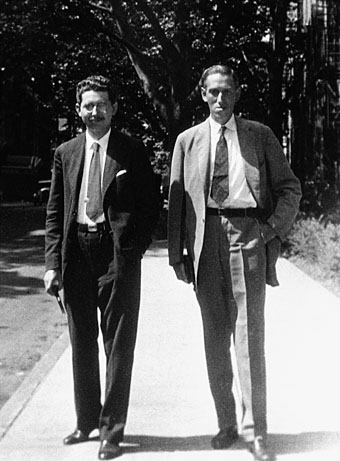

Frank Belknap Long and HP Lovecraft, New York, 1931. Photo by WB Talman.

Two friends—HP Lovecraft and Frank Belknap Long—visit the Egyptian antiquities in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1920s:

Tom Collins (for The Twilight Zone Magazine): I seem to recall a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art that you two made together.

Frank Belknap Long: You mean the time we visited the Egyptian tomb? Well, the Metropolitan apparently still has it. This was way back in the 1920s. The tomb was on the main floor in the Hall of Egyptian Antiquities, and we both went inside to the inner burial chamber. Howard was fascinated by the somberness of the whole thing. He put his hand against the corrugated stone wall, just casually, and the next day he developed a pronounced but not too serious inflammation. There was no great pain involved, and the swelling went down in two or three days. But it seems as if some malign, supernatural influence still lingered in the burial chamber—The Curse of the Pharaohs—as if they resented the fact that Howard had entered this tomb and touched the wall. Perhaps they had singled him out because of his stories and feared he was getting too close to the Ancient Mysteries.

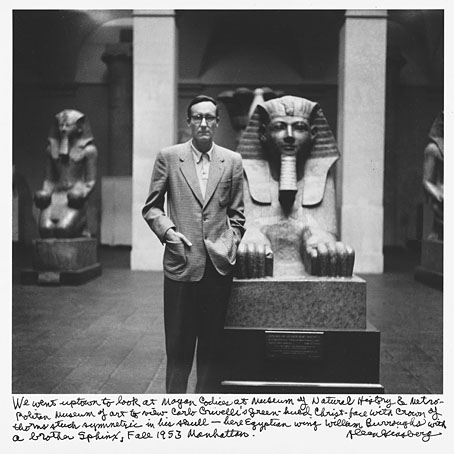

William Burroughs, New York, 1953. Photo by Allen Ginsberg.

Two friends—William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg—visit the Egyptian antiquities in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1950s:

Allen Ginsberg: We went uptown to look at Mayan Codices at Museum of Natural History & Metropolitan Museum of Art to view Carlo Crivelli’s green-hued Christ-face with crown of thorns stuck symmetric in his skull — here Egyptian wing William Burroughs with a brother Sphinx, Fall 1953 Manhattan.

When I last wrote about the parallels between Lovecraft and Burroughs in a post from 2014 I wasn’t aware of Lovecraft and Long’s visit to the same museum exhibits that Burroughs and Ginsberg visited some 30 years later. I did, however, use the same photos which are posted here, a curious coincidence when Long wasn’t mentioned in the earlier post. This minor revelation is a result of reading the features in back issues of The Twilight Zone Magazine, one of which is an interview with an 81-year-old Frank Belknap Long. The coincidence is a trivial thing but it adds to the small number of connections between the two writers.

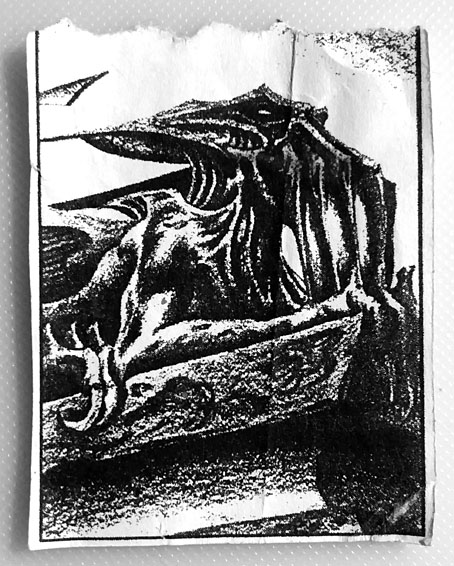

A Cthulhu Sphinx from The Call of Cthulhu, 1988.

Lovecraft and Burroughs were both living in New York City at the time of their excursions, and both touched on Egyptian mythology in their writings, so their having viewed the same museum exhibits seems inevitable rather than surprising. A more tangible connection between the pair is alluded to in Ginsberg’s photograph note when he mentions the Mayan codices. A few years before the museum visit, Burroughs had been studying the Mayan language and the Mexican codices in Mexico City under the tutelage of Robert H. Barlow, the former literary executor of HP Lovecraft. Burroughs’ studies subsequently fueled the references to Mayan mythology that turn up repeatedly in his fiction, and he was still at Mexico City College in 1951 when Barlow killed himself with a barbiturate overdose, afraid that his homosexuality was about to be exposed by one of his students. Burroughs mentioned the suicide in a letter to Ginsberg. The connections don’t end there, however. After Barlow’s death the rights to Lovecraft’s writings passed, somewhat controversially, to August Derleth and Donald Wandrei at Arkham House, and in another curious coincidence Derleth happened to be one of the complainants against a literary journal, Big Table, in 1959, when the magazine ran Ten Episodes from Naked Lunch, and was subsequently prosecuted for sending obscene material through the US mail. Derleth and Arkham House are both mentioned in the court papers.

I’ve never seen any indication that Burroughs was aware of these connections but if he was I doubt he would have paid them much attention, he always seemed rather blasé about his intersections with popular culture. He did think well enough of Lovecraft (or at least the version of Lovecraft’s fiction as presented by the Simon Necronomicon) to invoke “Kutulu” along with the Great God Pan and the usual complement of Mayan deities in Cities of the Red Night. Years later I remember seeing something in a newspaper about him retiring to Lawrence, Kansas, where he was described as passing the time “reading HP Lovecraft”. (I wish I could give a reference for this but I don’t recall the source.) If so then I like to think he might have given Creation Books’ Starry Wisdom collection more than a passing glance when it turned up at his door.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

• The William Burroughs archive