Pan teaching Daphnis to play the panpipes; Roman copy of a Greek original from the 3rd-2nd centuries BCE by Heliodoros.

“The worship of Pan never has died out,” said Mortimer. “Other newer gods have drawn aside his votaries from time to time, but he is the Nature-God to whom all must come back at last. He has been called the Father of all the Gods, but most of his children have been stillborn.”

So says a character in The Music on the Hill, one of the slightly more serious stories from Saki’s The Chronicles of Clovis (1911). Saki’s Pan is a youthful spirit closer to a faun than the goatish creature of legend. But being a gay writer whose tales regularly feature naked young men (surprisingly so, given the time they were written) I’m sure Saki would have appreciated the Roman statue above. There’s nothing chaste about this Pan with his “token erect of thorny thigh” as Aleister Crowley put it in his lascivious 1929 Hymn to Pan, a poem which caused a scandal when read aloud at his funeral some years later. The Roman statue was for a long while an exhibit in the restricted collection of the Naples National Archaeological Museum where all the more scurrilous and priapic artefacts unearthed at Pompeii were kept safely away from women, children and the great unwashed. These are now on public display and include the notorious statue of a goat being penetrated by a satyr.

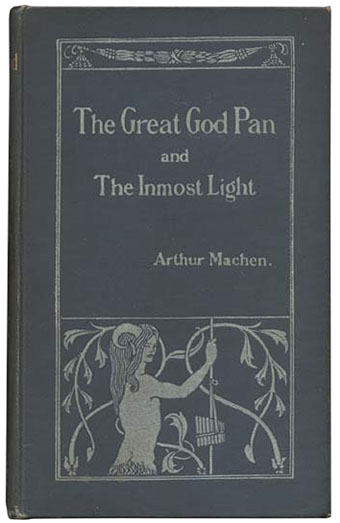

Aubrey Beardsley rarely wasted an opportunity to include a faun, satyr, herm or Pan figure in his early drawings, whether suitable or not. His title page for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé featured a herm (censored by the publisher) which had nothing to do with the play, and there’s a Pan figure brandishing pipes in his earlier How King Arthur Saw the Questing Beast, from the Morte D’Arthur. Beardsley was an increasingly celebrated artist by the time he was asked to illustrate the Keynotes series of novels for John Lane in 1893 and with Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan, the notoriety of the artist joined forces with an author whose weird tale was condemned as obscene, even as it established Machen as a uniquely gifted writer. Machen knew Crowley via The Golden Dawn and his tale of femme fatale Helen Vaughan was followed by an eruption of Edwardian paganism with Saki’s stories, A Touch of Pan and Pan’s Garden by Algernon Blackwood, The Blessing of Pan by Lord Dunsany, The Goat-Foot God by Dion Fortune and others. There’s even that curious moment in The Wind in the Willows whose seventh chapter, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, finds Mole and Rat having a mystical encounter:

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

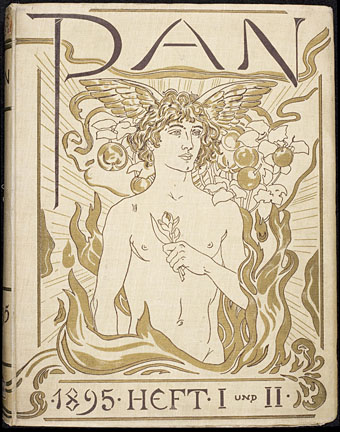

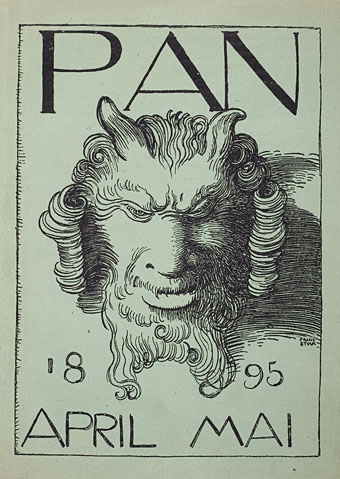

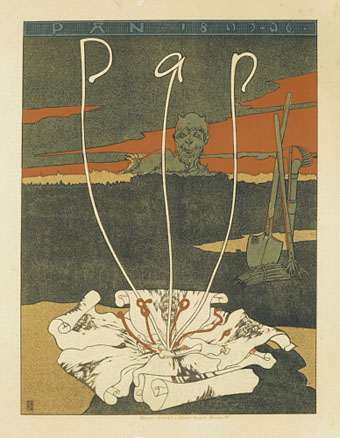

If the 18th century looked to the Classical world for order—especially where architecture was concerned—the 19th century seemed to find in Pan a spirit contrary to a world which was altogether too ordered, regimented and industrialised. Artists and writers in Germany seemed to think so when they named their Symbolist periodical after the pagan god. PAN was founded in 1895 and featured a stunning range of fin de siècle talent:

The journal PAN, which was published in Berlin between 1895 and 1900, is regarded as one of the most important voices of Art Nouveau in Germany. Edited by Otto Julius Bierbaum and Julius Meier-Graefem, the journal published numerous illustrations by well-known, and also unknown, young international artists. Additionally, there were full-page original designs, a simple modern typeface, vignettes and other forms of illustration. Some of the more well-known artists who published in PAN include Peter Behrens, Franz von Stuck, Max Klinger, Käthe Kollwitz, Auguste Rodin, Paul Signac and Félix Vallotton. Like the journal Jugend, PAN was critical about the artistic policy of the German Empire under Wilhelm. The journal attempted to present the very best of contemporary art, without showing preference for any particular school or movement, in order to allow comparison with classical art.

Cover by Franz Stuck.

PAN is featured regularly in books about the art of the period but for a long time there was next to nothing about the periodical on websites. That’s changed thanks to the Heidelberg University Library which has the bound collection whose cover is shown above available to view as high-res scans or to download as a single PDF. The text is in German, of course, but there’s a wealth of gorgeous Art Nouveau designs within, as well as many fine illustrations.

Joseph Sattler.

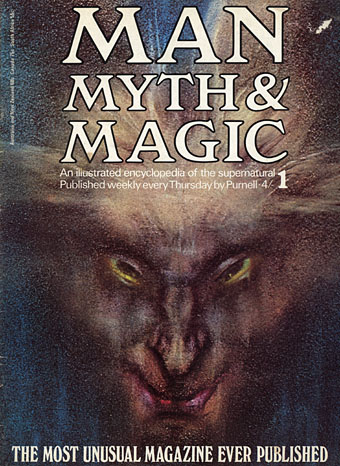

Man, Myth & Magic #1 (1970). Cover illustration is a detail of Elemental aka The Vampires are Coming aka Pan by Austin Osman Spare.

William Burroughs and Brion Gysin regularly mourned the death of Pan in the modern world, despite Burroughs invoking Pan’s spirit (among others) at the opening of Cities of the Red Night while Gysin maintained a lifelong devotion to the panpipe music of the Master Musicians of Joujouka. Pan Books still survives, albeit as a shadow of its former self, and filmgoers have found themselves lost in Pan’s Labyrinth; I produced a mis-proportioned Pan portrait of my own in 1986. There are many other examples to be found. Something about the primal archetype which Pan represents won’t be buried so easily. Pan isn’t dead; far from it, he’s as lively as ever.

Update: Take me into insanity | A Guardian piece about the Joujouka pipers.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Peake’s Pan

• Art Nouveau illustration

• Jugend Magazine

• Arthur Machen book covers

• Beardsley’s Salomé

• Hadrian and Greek love

• The Chronicles of Clovis and other sarcastic delights

I love my Man, Myth and Magic collection …

extraordinary images throughout …

The Wind in the Willows passage is one of the most beautiful things ive ever read – it gets me every time.And Machen has always been a favourite.

Mr Kenneth: I used MMM as a picture source for years. I’ve got a complete set in binders and nearly the whole of another set as loose copies.

Lord C: that chapter fascinates me for the way it implies another dimension to the book which is otherwise unexplored. A strange novel of disjunctions of which that episode is the most striking.

Machen has seldom, if ever, been acknowledged as being as important as he is to that entire circle of Lovecraft’s Weird Tale company. As with the Great God Pan, as with so many others, he mingled science and mysticism in a time when few had given that a second thought, oddly enough, since in antiquity they were inseparable. Antiquity being something of the utmost significance, among many other things, to all the writers in that circle.

To quote from HPL:

Despite the lavish praise, it’s true that many Lovecraft readers don’t work backwards to discover where the word AKLO (used in The Dunwich Horror) originated. Lovecraft as a child used to enjoy building pagan altars in the woods. It’s easy to imagine that if he hadn’t invented the Cthulhu Mythos he might have drawn substantially on pagan mythology for his stories.

So good to find other fans of Arthur Machen. . .and thanks for reprinting that piece from Wind in the Willows, I remember first reading it as a kid and understanding there was more to the book that furry-power. Pan isn’t dead and never went away; he’s at the heart of every man, waiting to be recognised and adored. Much more rewarding than, say, St Sebastian!

I researched the Joujouka singers for a book on Brian Jones. Definitely not Sufi/Muslim in origin, but possibly Gnostic.

It’s been so long since I read that Machen piece. I seem to remember it being more about just building up to the meeting with Pan (in a circular forest clearing?) and not being so much about a narrative. More a vignette than a story. But this was half a lifetime ago, so I could be wrong. I should reread it.

Joseph Sattler’s Pan cover!!

Great post. Love the synaptic links in lit you see.

And you shadow this trend for quite a span here, make me think Pan is the original Gay Mascot.

I also enjoyed Mordechai Gerstler’s children’s book on Pan.

I reviewed it on Goodreads, even though I felt a little sheepish (goatish?) doing so.

I mean, it’s supposed to be a children’s book.

But I enjoyed it so much.

The children’s author of the book on Pan is Mordicai Gerstein. Sorry. I invent people constantly through loss of memory.

The Machen story is a lot darker than that (Pan is a terrible force there) so you must be remembering another work. There’s so many Pan-related things around this time it’s hard to say what it might be. This reminds me that I ought to re-read the Blackwood stories.

Just locateded this brilliand communikation about Pan, and I do respect the rules about NOT valuation. Years ago I got this wonderful oilpainting form a auctionhouse i Denmark. The painting once hang in an Art & Craft house in the south of London.

http://www.c4antik.dk/katindex.asp?kukat=586

Best regards

Lars Krintel

Denmark.