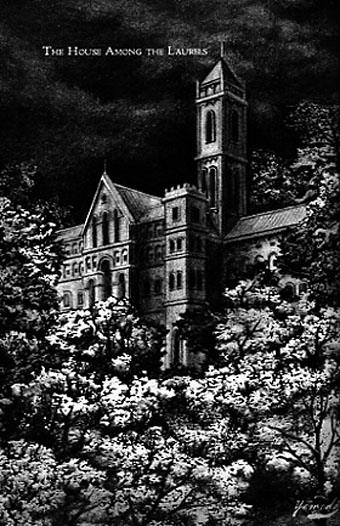

Coincidence time again: this ancient TV drama was posted to YouTube a few days ago just as I was finishing Timothy S. Murphy’s very commendable study of William Hope Hodgson’s fiction, William Hope Hodgson and the Rise of the Weird: Possibilities of the Dark. As drama or even basic entertainment, The Whistling Room is the opposite of commendable but it is notable for being the first screen adaptation of a Hodgson story. Hodgson’s fiction has never been popular with film or television dramatists. His two major weird novels, The Night Land and The House on the Borderland, would require lavish expenditure and special effects to do them justice, while the latter has a narrative shape and a lack of characterisation that would either repel any interest or incur considerable mangling of the story.

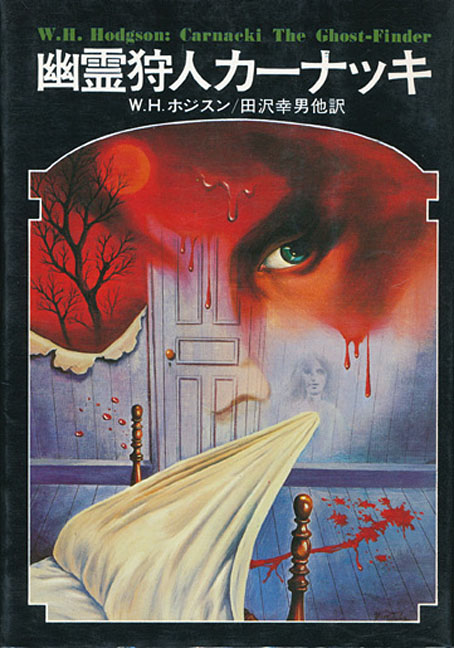

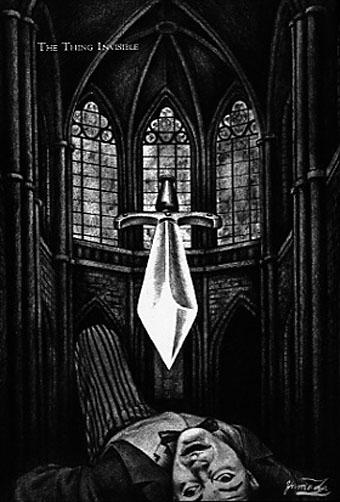

More appealing for screen adapters are Hodgson’s tales of Carnacki the Ghost Finder, a collection of short mysteries with a supernatural atmosphere and neat resolutions. The Whistling Room, a US production for Chevron Theatre in 1952, is the first of two Carnacki adaptations, the other appearing almost 20 years later when Thames TV included The Horse of the Invisible in their first series of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes. The Carnacki character was Hodgson’s take on the occult detective or psychic investigator, a short-lived offshoot of the post-Sherlock Holmes detection boom of the 1890s, and the concurrent interest in Spiritualism (or “Spiritism”, as Aleister Crowley always insisted it should be called). Carnacki is as resourceful and energetic as Hodgson’s other protagonists, and as an investigator he’s happy to use modern technology (electricity, cameras, vacuum tubes) to combat incursions from other dimensions. Hodgson’s descriptions of these encounters are freighted with all the capitalised terminology that recurs throughout The Night Land: “Outer Monstrosities”, “a Force from Outside”, “the Ab-human”. Carnacki’s exploits, however, have often been dismissed as hack-work when compared to the author’s novels or his tales of the Sargasso Sea. (The one Carnacki story that even detractors favour, The Hog, was a longer piece that only turned up many years after Hodgson’s death.) The stories are at their best when the mystery is an authentically supernatural menace, instead of another Scooby-Doo-like fraud being perpetrated by a disgruntled minor character.

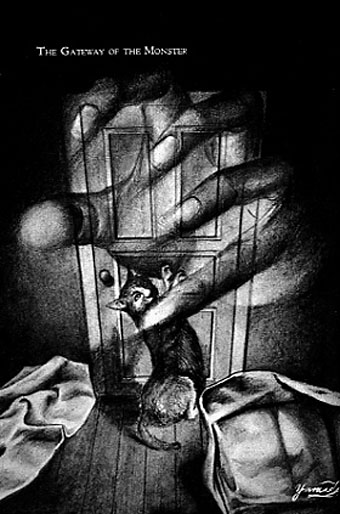

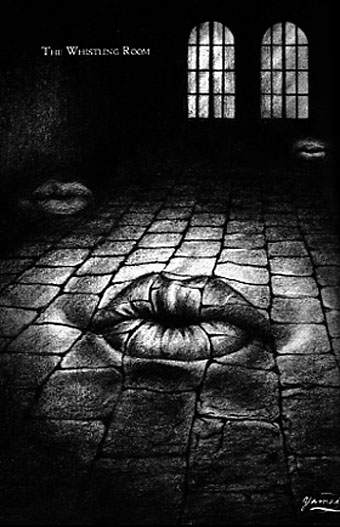

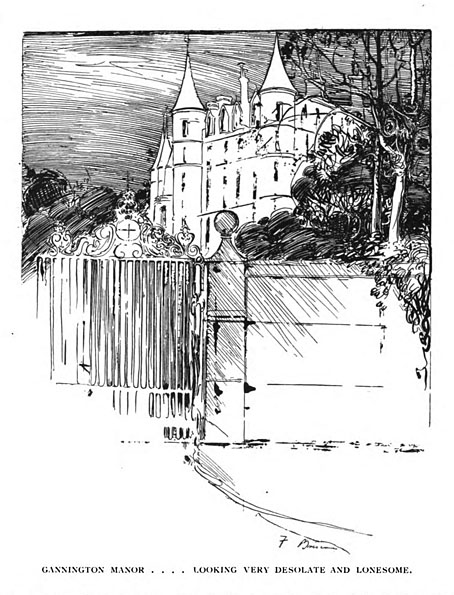

The Whistling Room was the third Carnacki tale from an early series of five that ran in The Idler in 1910. The story is one of those that concern genuinely supernatural events, and is essentially a repetition of the first of the Idler episodes, The Gateway of the Monster, in which a room in an old house is haunted by an antique curse that plagues the present owners. The room in question isn’t as deadly as the menace in the first story, the mysterious whistling (or “hooning”) being more of a threat to the nerves of the household than to life or limb. But the whistling soon resolves into a more material manifestation.

Whatever power the original story may possess is thoroughly absent from the TV adaptation, a mere sketch of a narrative that wasn’t very substantial to begin with. Alan Napier—Alfred the butler in the Batman TV series—is hopelessly miscast as Carnacki, being more of a bungling buffoon than any kind of serious investigator. There’s no mention here of Carnacki’s favourite occult tools, the “Saaamaaa Ritual” and the Sigsand Manuscript, while the closest we get to his Electric Pentacle is a ridiculous “Day-Ray”, a raygun-like emitter of captured sunlight that has no effect at all on the cursed room. The room itself and its mysterious whistling is more comical than frightening, with dancing furniture that wouldn’t be out of place in Pee-wee’s Playhouse, while the Irish setting of the story is signalled by terrible attempts at Irish accents from two of the actors. Nobody actually says “begorrah” or mentions leprechauns but much of the dialogue is pure stereotype. The adaptation by Howard J. Green even shunts the resolution into Scooby-Doo territory when one of the local lads is found to be partially responsible for the whistling noises, an explanation that Hodgson’s Carnacki goes to some trouble to rule from his investigation.

I wouldn’t usually write so much about something that scarcely deserves the attention but this film is such an obscure item we’re fortunate to be able to see it at all. I’ve been wondering what prompted the producers to choose this particular story. The Whistling Room was first published in the US in 1947, in the expanded Carnacki collection from Myecroft and Moran, an imprint of Arkham House. If Howard J. Green (or whoever) had taken the story from there then we have to wonder why he favoured this one over the others. I think it’s more likely that Dennis Wheatley’s A Century of Horror Stories (1935) was the source, a British anthology but one which would have had wider distribution than an Arkham House limited edition. The only other option listed at ISFDB is a US magazine, the final (?) issue of The Mysterious Traveler Mystery Reader. But this was published in 1952 which puts it too close to the TV production given the time required to commission and schedule an adaptation, even a poor one such as this. Whatever the answer, I feel that thanks are due to the uploader for making The Whistling Room available. Now that my curiosity has been assuaged I’ll return to hoping that someone eventually gives us a better copy of The Voice in the Night.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Jean-Michel Nicollet

• Suspicion: The Voice in the Night

• Hodgsonian vibrations

• The Horse of the Invisible

• Tentacles #2: The Lost Continent

• Tentacles #1: The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’

• Hodgson versus Houdini

• Weekend links: Hodgson edition

• Druillet meets Hodgson