Synchronicity is as universal as gravity. When you start looking you find it everywhere.

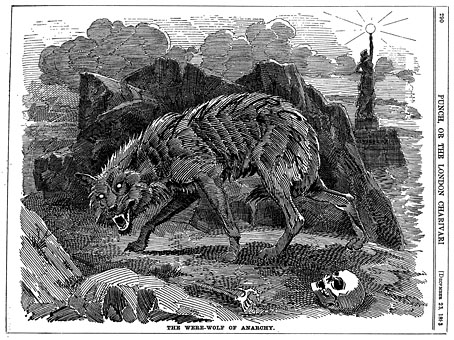

Thus Discordian anarchist Stella Maris, making her first appearance in my re-reading of Illuminatus! (previously) in a week when more synchronicities related to the novel have been imposing themselves. “The Werewolf of Anarchy” (published on the 23rd of the month, of course) was a picture that turned up a couple of days ago when I was searching through the back issues of Punch magazine. Punch did a lot of this kind of thing, dropping the humour now and then for some heavy-handed pictorial comment about international affairs. Given my current reading the word “anarchy” was bound to catch my attention but the werewolf image is unusual—why not a regular wolf?—while being further bound to the novel via Robert Anton Wilson’s fondness for Lon Chaney Jr’s lycanthrope. I often wondered why Wilson used to refer to this as much as he did. Illuminatus! mentions the werewolf legend from the first Universal film in its grab-bag of cultural weirdness, and I seem to recall there being more references in Wilson’s later novels. In the 1980s Wilson was living in Ireland where he wrote a werewolf-themed song with a local band, The Golden Horde, one of the few (only?) Irish groups who can be counted as part of the fleeting psychedelic revival that took place in the middle of the decade. The Golden Horde’s first album, The Chocolate Biscuit Conspiracy, appeared in 1985, and ends with Lawrence Talbot Suite, a number which is “explained” with the following words: “Lon Chaney Jr, The Easter Bunny, The primeval sleeve note, red curtain, the stings, a crush-can dominates a scowling buddha”. Whatever that means.

Meanwhile, my RSS feed informs me that Pentagrams Of Discordia have just released a new album whose final number bears the title Planetary Radiation (RAW); Robert Anton Wilson turns up again at the end of the track to talk about Chaos Theory in relation to Discordian history. And the above item arrived in the mail this week, a two-disc CD release of a newly-discovered live recording of Steve Hillage and band performing at the Bataclan in 1979. I own a lot of live Hillage albums, along with all his studio recordings, and this is one of the very best. The concert is pertinent for including an early rendition of New Age Synthesis (Unzipping The Zype), a song that made its first appearance in 1979 on the studio side of Live Herald, and which contains what may be the first reference to Illuminatus! in song form (the album sleeve includes thanks “to Robert Anton Wilson for his intriguing books”). Hillage offered an explanation of the studio songs’ lyrics in his own mysterious sleeve note:

For those who find the lingo a bit strange—“unzipping the zype” can be defined as (rising organ music please!):—the spontaneous inner exorcism by which a person can neutralise the harmful, consciousness-distorting effects of the artificial elemental spirits (zypes) formed around each word of everyday language.

The zypes are built up by the identification process by which we manufacture “reality.” Occultists refer to them as “astral glamour,” yogis as “the web of Maya”—but no word is zype-proof, not even zype. Cherish this phrase—it’s a royal flush!

Hmm, okay… No indication there or in the lyrics as to how you go about “unzipping the zype”. New Age Synthesis is a call-and-response between Hillage and partner Miquette Giraudy in which Hillage recounts his experience with the zypes. In the first verse he mentions “word spirits” to which Giraudy replies “Egregores!”, an occult concept which—quelle surprise—has connections to Chaos Magic. In the next verse Hillage blames the existence of the word spirits on the Illuminati—”Paranoia!” responds Giraudy—only to discard this claim in the lines that follow: “It isn’t really them at all, but you and me”. Hillage’s albums of the 1970s are filled with all manner of New Age business—flying saucers, ley lines, mysticism of various kinds—but he isn’t a David Icke. Why werewolves? What zypes? Mysteries abound. This is a great album, anyway, in or out of the Synchronicity Zone.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Ewige Blumenkraft

• Twinkle, twinkle little stars