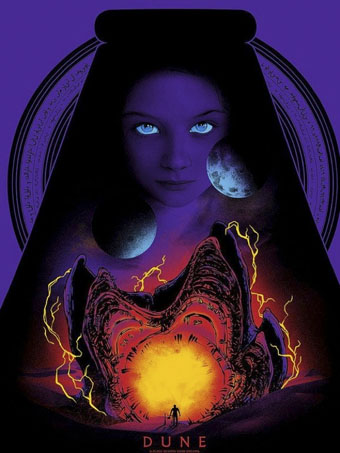

A Dune-inspired piece by Joshua Budich for In Dreams: an art show tribute to David Lynch at Spoke Art.

• “[Montague] Summers was a friend of Aleister Crowley and, like [Jacques d’Adelswärd] Fersen, conducted homoerotic black masses; whatever eldritch divinity received their entreaties was evidently propitiated by nude youths.” Strange Flowers goes in search of the Reverend Summers.

• More Jarmania: Veronica Horwell on the theatrical life of Derek Jarman, Paul Gallagher on When Derek Jarman met William Burroughs, and Scott Treleaven on Derek Jarman’s Advice to a Young Queer Artist.

• Robert Henke of Monolake talks to Secret Thirteen about his electronic music. More electronica: analogue-synth group Node have recorded a new album, their first since their debut in 1995.

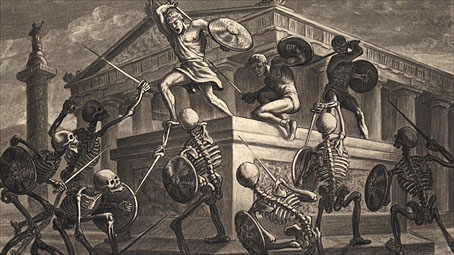

This hypertrophied response to decay and dilapidation is what drives the “ruin gaze”, a kind of steroidal sublime that enables us to enlarge the past because we cannot enlarge the present. When ruin-meister Giovanni Piranesi introduced human figures into his “Views of Rome”, they were always disproportionately small in relation to his colossal (and colossally inaccurate) wrecks of empire. It’s not that Piranesi, an architect, couldn’t do the maths: he wasn’t trying to document the remains so much as translate them into a grand melancholic view. As Marguerite Yourcenar put it, Piranesi was not only the interpreter but “virtually the inventor of Rome’s tragic beauty”. His “sublime dreams”, Horace Walpole said, had conjured “visions of Rome beyond what it boasted even in the meridian of its splendour”.

Frances Stonor Saunders on How ruins reveal our deepest fears and desires.

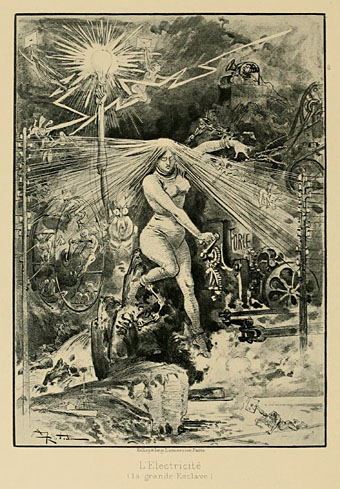

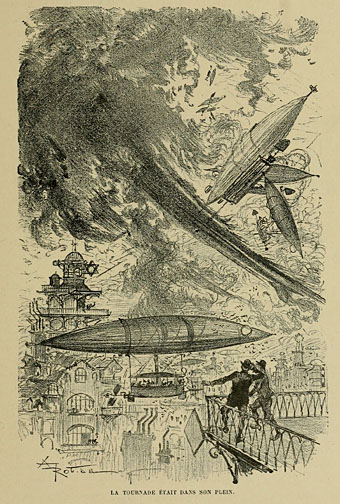

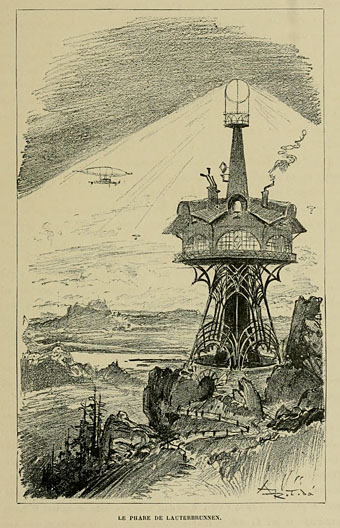

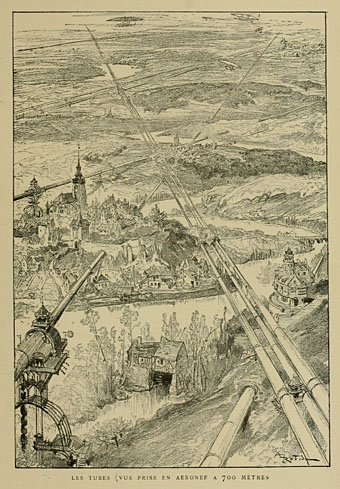

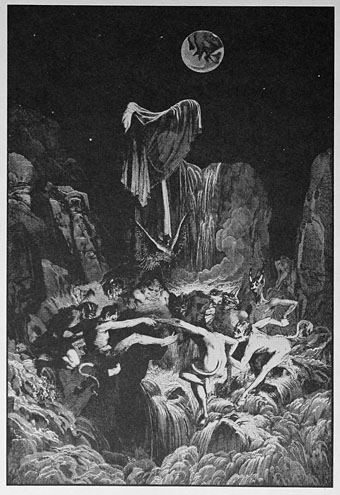

• Gustave Doré. L’imaginaire au pouvoir: Four short films from the Musée d’Orsay to accompany their current exhibition, Gustave Doré (1832–1883): Master of Imagination.

• At Dangerous Minds: Remembering Cathy Berberian, the hippest—and funniest—lady of avant-garde classical music.

• “Merely a Man of Letters”: Jorge Luis Borges interviewed in 1977 by Denis Dutton & Michael Palencia-Roth.

• Luke Epplin on Big as Life (1966), a science-fiction novel by EL Doctorow which the author has since disowned.

• The Psychomagical Realism of Alejandro Jodorowsky: Eric Benson talks to the tireless polymath.

• A video essay by Matt Zoller Seitz for the 10th anniversary of David Milch’s Deadwood.

• Eugene Brennan on Scott Walker’s The Climate of Hunter (1984).

• Dune at Pinterest.

• Prophecy Theme from Dune (1984) by Brian Eno | Olivine (1995) by Node | Gobi 110 35′ south 45 58′ (1999) by Monolake