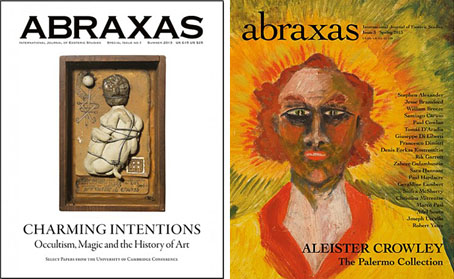

A welcome arrival in the post recently was two issues of Abraxas, the book-format journal of esoteric studies from Fulgur Esoterica. I’ve always observed the contemporary occult scene from a distance, being more interested in cultural spin-offs whether those happen to be music-oriented—as was the late, lamented Coil—or art-oriented. Something I always enjoyed about Kenneth Grant’s books was the amount of unique art material they contained, much of it by his wife, Steffi Grant, or previously unseen work by Austin Osman Spare. Fulgur have for many years continued this artistic focus, starting out by reprinting Spare’s books (and publishing new ones, such as the revelatory Zos Speaks!), and more recently turning their attention to the work of contemporary artists following similar paths.

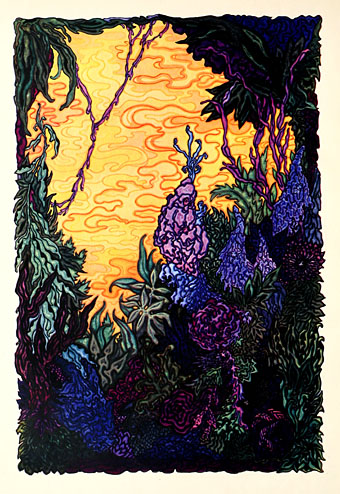

Study for Salome (2012) by Denis Forkas Kostromitin.

Abraxas is a venue for the latter group, especially in the most recent issue, no. 3, which features a wealth of new art, photography, essays and poetry. In the past I’ve complained about the misunderstandings Austin Spare’s work used to generate among otherwise intelligent and sensitive critics when faced with the artist’s occult obsessions; the usual response would be to lazily dismiss this side of his work as “black magic”, and therefore either kitsch or nonsense. Things have improved in recent years but it’s taken a long time for critics and curators who would show the greatest respect to a minority belief from South America, say, to offer the same respect to equally sincere artists who happen to be working in London or New York. One of the values of Abraxas for artists such as Jesse Bransford and Denis Forkas Kostromitin, both of whom are interviewed here, is that they can have a conversation with someone who won’t treat their work or their interests in a condescending manner. I’m particularly taken with Kostromitin, a Russian artist whose work I only discovered recently.

M L K (Moloch) (2011) by Denis Forkas Kostromitin.

Elsewhere in Abraxas 3 there’s a feature on the recent exhibition of Aleister Crowley’s extravagant daubs, an article by Francesco Dimitri about tarantism in southern Italy, a piece about Dada by Adel Souto, and text by Paracelsus with illustrations by Joseph Uccello which is printed on a different paper stock. The production quality is as good as any art book but then that’s standard for a Fulgur publication. Mention should be made of the interior design of this issue which far exceeds the often perfunctory layout of many publications from smaller publishers. Tony Hill is credited on the masthead as Creative Director so I’m assuming he’s the person responsible. Abraxas is an essential purchase for anyone interested in contemporary occult art. The hardback of no. 3 is a limited edition that includes a signed and numbered lithograph by Denis Forkas Kostromitin.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• I:MAGE: An Exhibition of Esoteric Artists