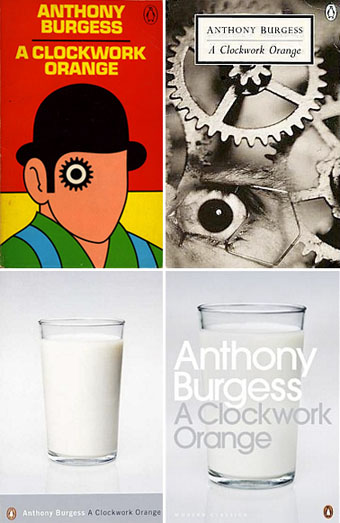

top left: David Pelham’s classic design (1972); top right: photography

by Lionel F Williams (Eye) and SOA / Photonica (Cogs) (1996).

bottom left and right: photography by Véronique Rolland (2000 & 2008).

In April this year I wrote about James Pardey’s excellent site devoted to book covers from the Penguin science fiction range. I’m often pointing to various book cover galleries on Flickr and elsewhere but James’s site goes far beyond these, with credits and annotations for every cover on display. He emailed this week to let me know that his site has been considerably expanded, from 160 covers to 250 (!), bringing the timeline closer to the present. In addition the site has improved page layouts which enable you to study the evolution of each title. All design sites should be this good.

And coincidentally, Anne S mentioned in the comments yesterday that she’s been adding some Penguin Classics covers to her Eye Candy for Bibliophiles site. Lots of other worthwhile viewing there, including some of the old Puffin covers for Alan Garner.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Penguin science fiction

• A Clockwork Orange: The Complete Original Score

• Penguin Labyrinths and the Thief’s Journal

• Penguin Surrealism

• Juice from A Clockwork Orange

• Penguin book covers

• Clockwork Orange bubblegum cards

• Alex in the Chelsea Drug Store