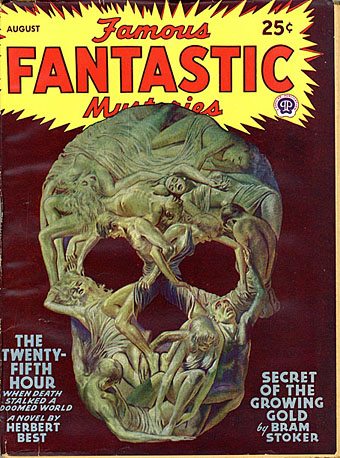

Famous Fantastic Mysteries (August, 1946).

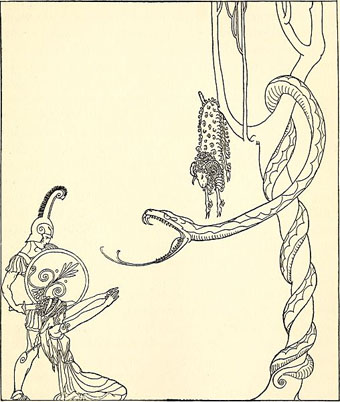

Salvador Dalí and Philippe Halsman popularised the image of a human skull created by an arrangement of bodies in Halsman’s 1951 photo-portrait of the artist, In Voluptas Mors. The assemblage, which was based on a sketch by Dalí, has been imitated by photographers and poster designers but I’ve yet to see any mention of this painted precursor by illustrator Lawrence Sterne Stevens (or “Lawrence” as he was always credited) for Famous Fantastic Mysteries in August, 1946. I’d assume the similarity is a coincidence. The subliminal skull in painting and drawing goes back at least as far as the 1890s (see this post), while Dalí was always very adept at finding and creating visual rhymes. Variations on the skull-from-figures motif appear in paintings throughout his career, one of the earliest being a minor work, Dancer – Skull, from the 1930s. Another painting, a commission for a wartime poster warning US soldiers about the hazards of venereal disease, features a pair of women, and predates Lawrence’s cover by four years.

In Voluptas Mors (1951).

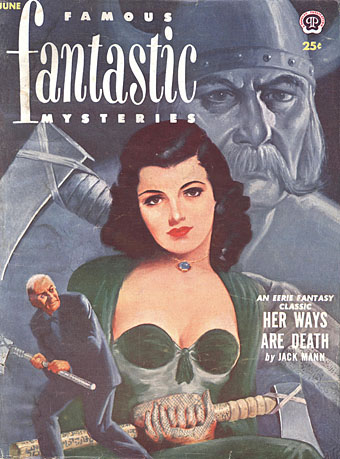

Lawrence deserves credit, however, for having created a more successful arrangement of bodies than Halsman and Dalí managed, although it’s easier to do this in a painting than it is to arrange a group of women in a studio. Some of the limbs of Lawrence’s figures are extended or foreshortened, while the contrast between light and shade has been reduced to aid the composition. Lawrence painted a further variation on the subliminal skull in a cover for Famous Fantastic Mysteries the year after the Dalí/Halsman portrait, while Dalí himself returned to the theme with Skull of Zurbarán in 1956.

Famous Fantastic Mysteries (June, 1952).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Être Dieu: Dalí versus Wakhévitch

• Chance encounters on the dissecting table

• Salvador Dalí’s Maze

• Dalí in New York

• Dalí’s discography

• Soft Self-Portrait of Salvador Dalí

• Mongolian impressions

• Hello Dali!

• Dirty Dalí

• The skull beneath the skin

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie revisited