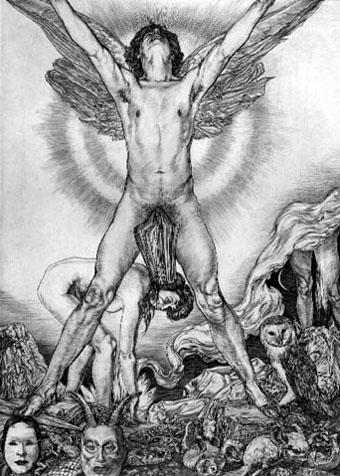

Europe: A Prophecy by William Blake (1794).

Two exhibitions based around the work of William Blake open today at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery, Mind-Forg’d Manacles, “organised to coincide with the 250th anniversary of Blake’s birth as well as the 200th anniversary of the Parliamentary abolition of the transatlantic slave trade” and Blake’s Shadow: William Blake and his Artistic Legacy. The latter seems to be the more interesting of the two.

Blake’s Shadow: exhibition summary

This exhibition explores Blake’s continuing fascination for artists, filmmakers and musicians. It features around sixty watercolours, prints and paintings in addition to numerous illustrated books and a range of audio-visual material. Blake is a unique figure in British visual culture, attracting both academic and popular interest. In the years since his death in 1827, Blake has continued to influence the world of creativity and ideas. He has inspired people with such wide ranging interests as literature, painting, book design, politics, philosophy, mythology through to music and film making. Alongside works by Blake—prints, watercolours, engravings and book illustrations—the exhibition spans two centuries of his influence.

• His contemporaries in the late 18th and early 19th century are represented with works from John Flaxman, Edward Calvert, Samuel Palmer, J.H. Fuseli and Thomas Stothard

• Blake’s influence on artists in the Victorian period is explored through works by Ford Madox Brown, Walter Crane, Frederic Shields, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Simeon Soloman and G.F. Watts.

• British artists working in the 20th and 21st century include Cecil Collins, Douglas Gordon, Paul Nash, Anish Kapoor, David Jones, Ceri Richards, Patrick Proctor, Austin Osman Spare and Keith Vaughan. This section of the exhibition features photographs and original works.

• From the 1960s onward, writers, musicians, film makers like Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison of The Doors and John Lennon have adopted Blake as a mystical seer and anti-establishment activitist. More latterly, as British musicians and activists like Billy Bragg and Julian Cope have grappled with notions of national identity, Blake has enjoyed something of a renaissance. Blake’s Shadow examines this more recent influence as evidenced in work by the filmmakers Jim Jarmusch and Gus Van Sant, and various musicians, notably Patti Smith and Jah Wobble.

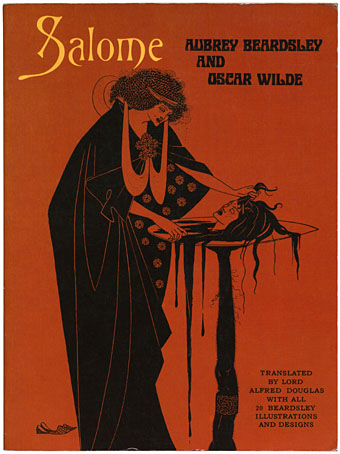

The Dawn by Austin Spare (no date).

It’s good to see Austin Spare being included in something like this. He always referred to Blake as an influence but, as I’ve mentioned before, he’s frequently been treated disrespectfully by an art establishment that doesn’t know what to make of the occult basis of his work.

Mind Forg’d Manacles runs to 6 April 2008, Blake’s Shadow to 20 April.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Austin Spare in Glasgow

• Tygers of Wrath

• Austin Osman Spare