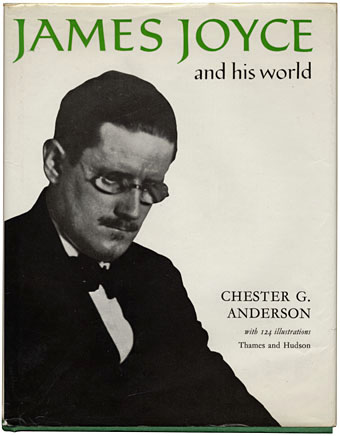

James Joyce and his World (1978).

Despite my earlier statement about not being much of a collector, today’s book purchase (above) was enough to confirm some well-established patterns (obsessions, even) that should make me reconsider any hasty pronouncements. Not so much for the subject in this case—I already have enough books by and about James Joyce—the significant thing here is the three magic words on the cover: Thames and Hudson. The sight of Joyce’s name on the spine above the old T&H dolphin logo (signifying the two rivers that comprise the company’s name; or maybe a discourse between London and New York via the Atlantic) was enough to demand further investigation. I realised I’d been hoping to eventually find this book after seeing it listed in the back of its companion title, Beardsley and his World by Brigid Brophy. Both books form part of a series that T&H produced in the Seventies, a collection of heavily illustrated mini-biographies of writers, with the odd artist among them. Very worthwhile they are too, with lots of photographs, paintings or drawings of the people and places relevant to their subjects’ lives.

Despite my earlier statement about not being much of a collector, today’s book purchase (above) was enough to confirm some well-established patterns (obsessions, even) that should make me reconsider any hasty pronouncements. Not so much for the subject in this case—I already have enough books by and about James Joyce—the significant thing here is the three magic words on the cover: Thames and Hudson. The sight of Joyce’s name on the spine above the old T&H dolphin logo (signifying the two rivers that comprise the company’s name; or maybe a discourse between London and New York via the Atlantic) was enough to demand further investigation. I realised I’d been hoping to eventually find this book after seeing it listed in the back of its companion title, Beardsley and his World by Brigid Brophy. Both books form part of a series that T&H produced in the Seventies, a collection of heavily illustrated mini-biographies of writers, with the odd artist among them. Very worthwhile they are too, with lots of photographs, paintings or drawings of the people and places relevant to their subjects’ lives.

So I finished

So I finished