When it comes to film and TV dramas based on the writings of HP Lovecraft I’ve always been very selective, to a degree that I avoid most adaptations unless they receive reviews good enough to provoke my curiosity. I do, however, keep an eye out for unusual (or unusually inventive) adaptations whose shortcomings I’m prepared to forgive if they promise to be more than another wearying trudge through cinematic cliches. Such is the case with this Japanese TV adaptation of The Shadow Over Innsmouth which was written and directed by Chiaki Konaka in 1992.

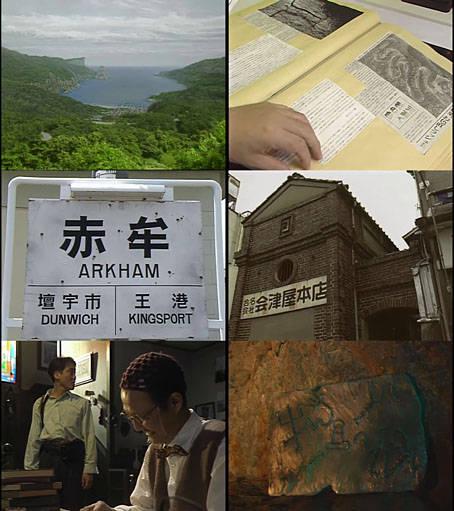

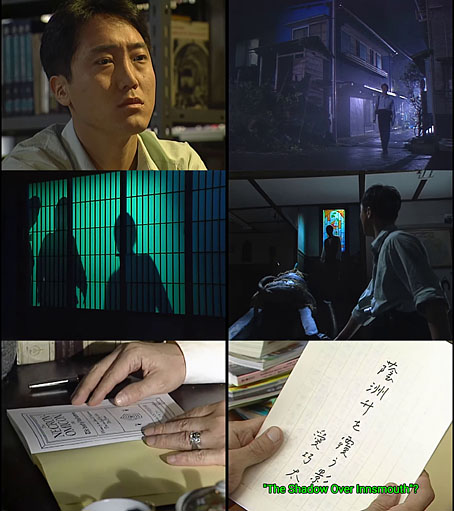

Konaka’s adaptation isn’t immediately attractive, being shot entirely on video, a very unsympathetic format for horror productions when the harshness of the image works against any attempts to create an eerie atmosphere. (Even The Stone Tape suffers in this area.) Konaka presents a sketch of Lovecraft’s story which he updates to the present day and moves to contemporary Japan, with no explanation as to why the Japanese coastline is a home to towns with names like “Innsmouth”, “Arkham” and “Dunwich”. Lovecraft’s detailed history of the blighted backwater and its inhabitants is also ignored. Konaka’s narrative begins with an unnamed photo-journalist (Renji Ishibashi) securing a job at a travel magazine where he convinces the editor that the remote coastal town of “Insumasu” is worthy of a feature. As with the anonymous narrator of Lovecraft’s story, the photographer is drawn to the place as much by ancestral impulses as by his curiosity about a place where a strange fish-human corpse has been washed ashore.

Konaka’s direction is more functional than suspenseful, with the photographer’s biographical history telegraphed so much in advance that none of the revelations come as a surprise. The soundtrack is also very uneven, being a collage of music borrowed from other films: there’s a brief snatch of Goblin’s Suspiria score at one point, and I think the repeated flute refrain is borrowed from a Preisner score. This is a well-made adaptation all the same even if the Japanese Innsmouth isn’t as deteriorated as the decayed fishing town that Lovecraft describes. (To be fair, any film depicting Lovecraft’s Innsmouth would require a serious budget to do the place justice.) Fishy details abound, and Konaka uses green light as a recurrent motif that refers to Innsmouth’s secret history, like an inversion of the emerald glow that signifies magic or the supernatural in John Boorman’s Excalibur. I was especially pleased to see borrowings from the George Hay Necronomicon during a cermonial invocation to Dagon that takes place in a cave. Later on we see a copy of the Hay book being perused by the curator of the Innsmouth museum. This makes a change from the tiresome ubiquity of the “Simon” Necronomicon whose sigils are always turning up in Lovecraftian adaptations when people are at a loss to create symbols of their own. The symbology in the Hay book was the work of Robert Turner, an occultist with an aesthetic sensibility more finely attuned to the world of the Cthulhu Mythos.

Chiaki Konaka has been described as bringing a Lovecraftian influence to his other work but when most of this is anime scripts for juvenile fare like the Digimon franchise you can’t expect very much. One of his credits is for something called Cthulhu’s Secret Record but I’ve no idea what this might be. Konaka’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth many be viewed in full here. The translated subtitles are larger than I prefer (and in vivid green) but I’m still pleased that someone went to the trouble of making this curio available to a wider audience.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive