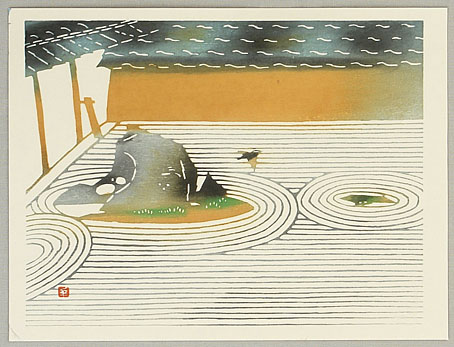

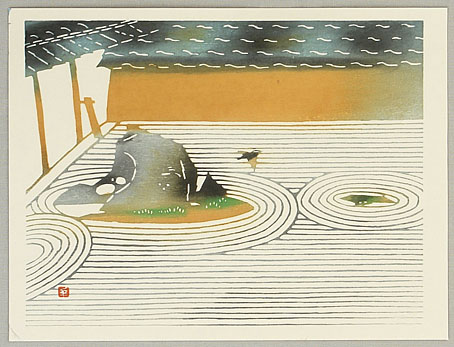

Miniature Zen Garden (1895) by Unknown.

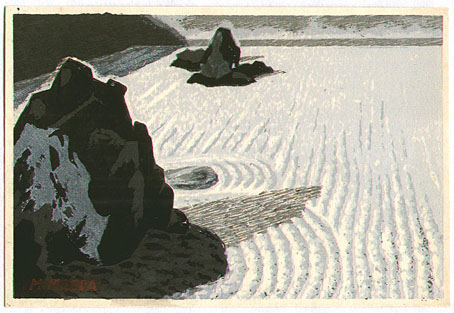

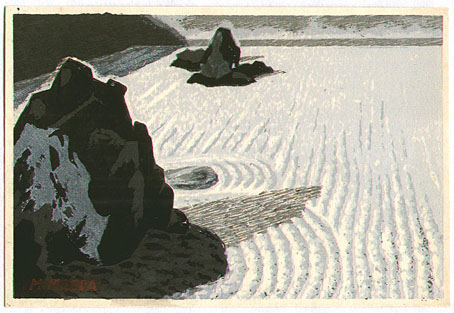

Ryoan-ji Temple (Mid-20th C.) by Inagaki Toshijiro.

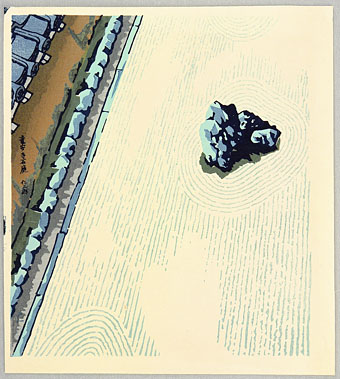

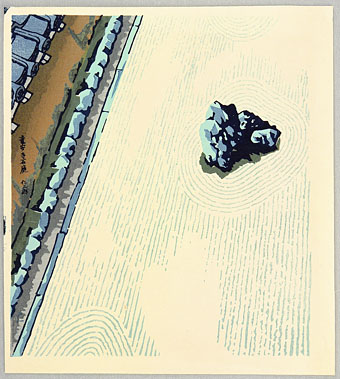

Ryoan-ji Temple (Mid-20th C.) by Maeda Masao.

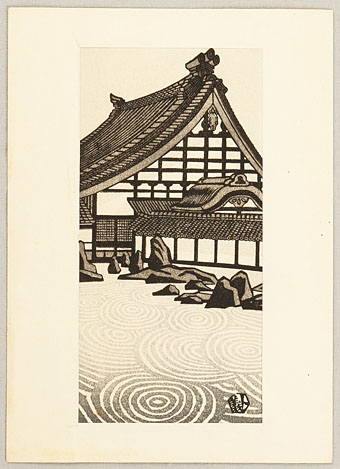

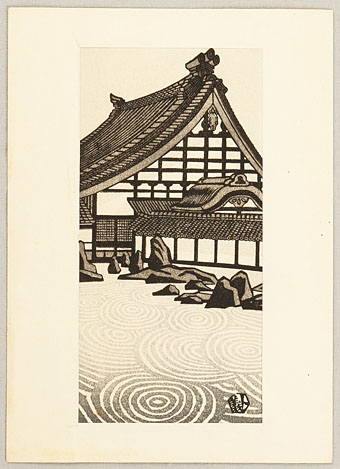

Stone Garden of Ryoan-ji Temple (c.1950s) by Ito Nisaburo.

Ryoan-ji Zen Garden (c.1950s) by Okuyama Gihachiro.

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Architecture

Miniature Zen Garden (1895) by Unknown.

Ryoan-ji Temple (Mid-20th C.) by Inagaki Toshijiro.

Ryoan-ji Temple (Mid-20th C.) by Maeda Masao.

Stone Garden of Ryoan-ji Temple (c.1950s) by Ito Nisaburo.

Ryoan-ji Zen Garden (c.1950s) by Okuyama Gihachiro.

Soap Bubble (1882) by Alexandre-Blaise Desgoffe. Via.

• “…there is not now, has never been, and will never be a single Platonic form of the paragraph to which all others must conform.” Richard Hughes Gibson on the history of the paragraph.

• At Spoon & Tamago: imaginary covers by international illustrators for The Tokyoiter, a New Yorker-style magazine about the Japanese capital.

• New music: tick tick tick by Stephen Mallinder, and A Vibrant Touch by Aleksandra Slyz.

The Kat had a cult following among the modernists. For Joyce, Fitzgerald, Stein, and Picasso, all of whose work fed on playful energies similar to those unleashed in the strip, he had a double appeal, in being commercially nonviable and carrying the reek of authenticity in seeming to belong to mass culture. By the thirties, strips like Blondie were appearing daily in roughly a thousand newspapers; Krazy appeared in only thirty-five. The Kat was one of those niche-but-not-really phenomena, a darling of critics and artists alike, even after it stopped appearing in newspapers.

Amber Medland on George Herriman, EE Cummings and Krazy Kat

• 35mm.online: Polish feature films, documentaries and animations, all free to view.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…Georges Bataille Erotism: Death and Sensuality.

• Inside the Espai Corberó, the home/gallery of the late Xavier Corberó.

• Strange Attractor Journal Five.

• RIP Claes Oldenburg.

• Krazy Kat (1928) by Frankie Trumbauer & His Orchestra | Krazy Kat (1949) by Artie Shaw | Krazy Kat (1975) by Teddy Lasry

Another new cover of mine, this one suits the weather which today in Britain is giving us temperatures more usually found in regions further south:

From debut author Hadeer Elsbai comes the first book in an incredibly powerful new duology, set wholly in a new world, but inspired by modern Egyptian history, about two young women—Nehal, a spoiled aristocrat used to getting what she wants and Giorgina, a poor bookshop worker used to having nothing—who find they have far more in common, particularly in their struggle for the rights of women and their ability to fight for it with forbidden elemental magic.

As a waterweaver, Nehal can move and shape any water to her will, but she’s limited by her lack of formal education. She desires nothing more than to attend the newly opened Weaving Academy, take complete control of her powers, and pursue a glorious future on the battlefield with the first all-female military regiment. But her family cannot afford to let her go—crushed under her father’s gambling debt, Nehal is forcibly married into a wealthy merchant family. Her new spouse, Nico, is indifferent and distant and in love with another woman, a bookseller named Giorgina…. (more)

The design bears a superficial resemblance to the one I created for The Ingenious by Darius Hinks, one of the requests from the art director being for a similar view down a street and the sky filled with an interlaced pattern. The new artwork isn’t as fantastic, however, since the city of Almaxar in Hadeer’s novel is based on old Cairo. This was very convenient for the research process, Cairo was a popular destination for western travellers in the 19th century so there are many sketches and engravings of its narrow lanes. My street is an amalgam of several different views, with an emphasis on those mashrabiya windows which are designed to help cool buildings. (On a side note, the subject of ventilation and passive cooling in Middle-Eastern architecture is a fascinating one, as this page about windcatchers demonstrates.)

The knotwork pattern was the third design I tried after the first two turned out to be too obtrusive for the background. Both this one and the pattern used for The Ingenious were taken from templates in Les Éléments de l’Art Arabe – Le Trait des Entrelacs (1879) by Jules Bourgoin, a book which shows how to create these interlacings from scratch. I always prefer to do this when possible, rather than using stock imagery; the creation of the pattern doesn’t take too long once you’ve worked out the portion that will be repeated.

The Daughters of Izdihar will be published early next year by Harper Voyager (US) and Orbit Books (UK).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Ingenious by Darius Hinks

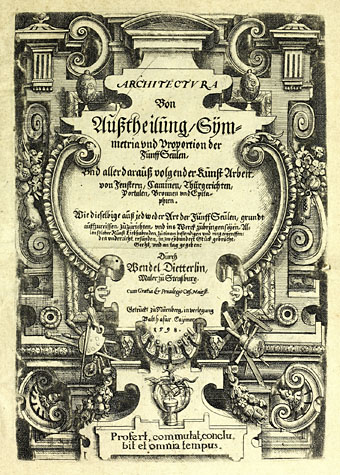

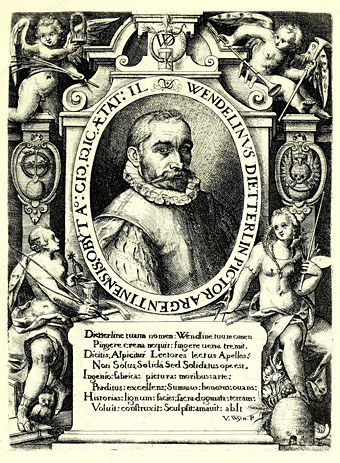

While looking through my bookshelves recently for examples of Baroque architecture I was reminded of the eccentric designs of Wendel Dietterlin (c. 1550–1599), a German painter and engraver whose Architectura (1598) is less a guide to architectural form than an excuse to indulge the artist’s fervid imagination. This wasn’t really the reference material I was after—Dietterlin is pre-Baroque—but I’d not seen so much of his work in one place before. Dover Publications have reprinted all of these plates for many years as The Fantastic Engravings Of Wendel Dietterlin but it’s one Dover book I’ve never owned.

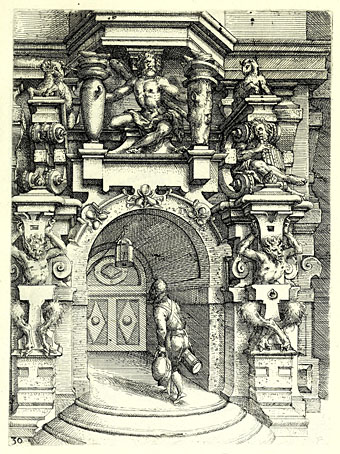

“Fantastic” is an apt description. Where a similar study might present the reader with careful elaborations of Vitruvian principles, Dietterlin offers plate after plate of suggestions for portals, fountains, fireplaces and facades, many of which are festooned with bizarre and grotesque details. Wild animals are a persistent theme. Other artists of the period tended to favour mythological scenes for fountain sculpture; Dietterlin shows a series of large animals being attacked by smaller ones: bear versus dogs, dragon versus men, and so on. Similar groupings may be found on his designs for rustic arches. Ostensibly these are traditional hunting scenes but there’s a fury in Dietterlin’s renderings that pushes the representations away from the decorative towards the pathological.

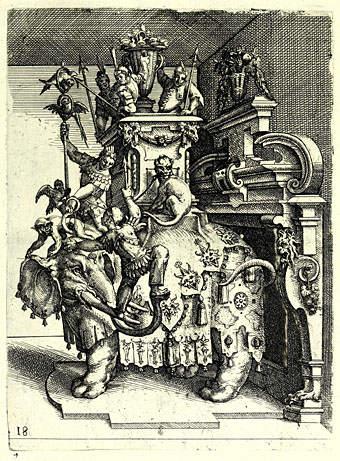

In other designs the wildness is transferred to the decoration itself. Examples of the traditionally sober orders of Classical architecture are shown encrusted with decorations added at the whim of the artist; Dietterlin wasn’t the only artist to do this but other artists are seldom this excessive. Strangest of all is the plate that shows a huge elephant standing before (or emerging from) a fireplace. René Passeron included a handful of engraving artists in the precursors section of his Concise Encyclopedia of Surrealism in 1975, but Dietterlin isn’t among them. I’d say that elephant alone is suitable qualification, a forerunner of Magritte’s Time Transfixed, as well as a literal (if inadvertent) representation of “the elephant in the room”.

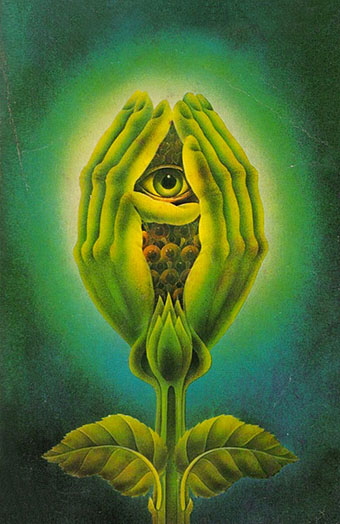

Cover art by Alan Aldridge for The Secret Life of Plants, 1975. Via.

• At Aquarium Drunkard: Alice Coltrane and band in a furious live performance at the Berkeley Community Theatre, 1972. The audio is on YouTube, and was also released on (unofficial) vinyl a couple of years ago, but you can download the whole set at Dimeadozen. (Free membership required.)

• “Black Square is tragic; it’s absurd; it can be bewildering or funny; it’s certainly metaphysical; and now it serves as a precursor for works and projects yet to be imagined.” Andrew Spira on the precursors of Black Square by Kazimir Malevich.

• “The possibility of plant consciousness cuts two ways, depending on whether you see plants as friend or foe, benevolent or threatening.” Elvia Wilk on the secret lives of plants.

• New/old music: Robot Riot by Stereolab. A previously unreleased recording from the mid-90s which will appear on the fifth instalment in the Switched-On compilation series.

• “Dare’s good, but Love And Dancing broke the mould and kicked off the whole modern dance scene.” Ian Wade on 40 years of remix albums.

• Coming soon from Strange Attractor: Arik Roper: Vision of The Hawk.

• At Unquiet Things: Deborah Turbeville’s unseen Versailles.

• “Thinking like a scientist will make you happier”.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Karel Zeman Day.

• Plantasia (1976) by Mort Garson | Musik Of The Trees (1978) by Steve Hillage | The Secret Life Of Plants (1979) by Stevie Wonder