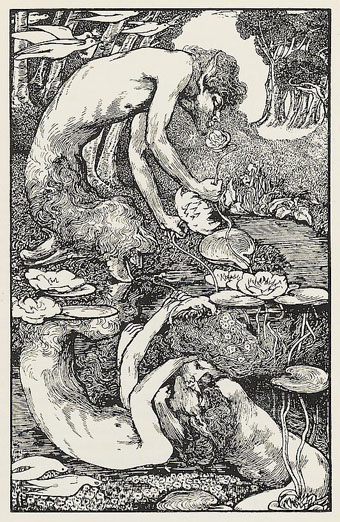

Another one to add to the stock of fauns, satyrs and Pan figures that proliferate from the 1890s to the 1920s, Laurence Housman’s The Reflected Faun appeared in The Yellow Book in 1894. The magazine’s publisher, John Lane, also published Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan in the same year although an early version of Machen’s story had appeared a few years before. What’s notable about Housman’s drawing is the way he combines in a single image several distinct themes: Faunus/Pan, the reflected Narcissus, and all those tales of beguiling spirits lurking in water. The nature of the spirit in this picture is distinctly androgynous, a detail that wouldn’t have impressed those critics who considered The Yellow Book to be an unwholesome publication. The androgyny may be taken as deliberate: Housman was one of London’s “Uranian” artists, and a few years later joined George Cecil Ives’ Order of Chaeronea, a secret society for gay men and lesbians. In the light of this, the drawing might be interpreted as a symbol for a clandestine existence where true desires remain buried or submerged.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Aubrey Beardsley’s Keynotes

• In the Key of Yellow

• Ads for The Yellow Book

• The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

• The Great God Pan

• Peake’s Pan