The Frog with Rabbit Ears (1891).

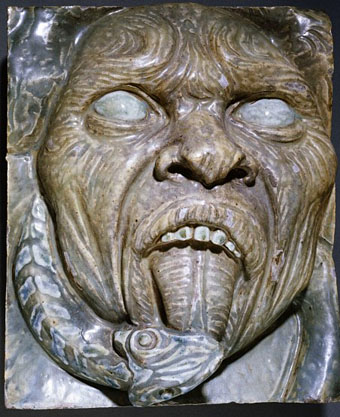

La matière de l’étrange, an exhibition of ceramic grotesques by Jean Carriès is currently running at the Petit Palais, Paris, through to January 27th, 2008. Carriès doesn’t feature in any of my books about eccentric or fantastic artists which I find surprising, his work is very peculiar by 19th century standards, looking like the creation of a Rodin obsessed by Lautréamont. Carriès’ series of “horror masks” are so similar to the earlier series of heads by sculptor Franz Messerschmidt I suspect there may be an influence there. And like Rodin, Carriès also had unsuccessful plans for a monumental gateway ornamented with his figures and scowling faces. Unlike Rodin, his plaster draft of the work was destroyed by a criminally unsympathetic curator but the Petit Palais exhibition attempts a reconstruction based on a model by Eugène Grasset.

Thanks to Nathalie for the tip!

• English article at The Art Tribune

• French page with video of the exhibition

Head of a Faun (1890–92?).

Grotesque mask, element for the Monumental Door (1891–94).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Masks of Medusa

• Bernini’s Anima Dannata

• The art of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, 1736–1783

• The art of Stanislav Szukalski, 1893–1987

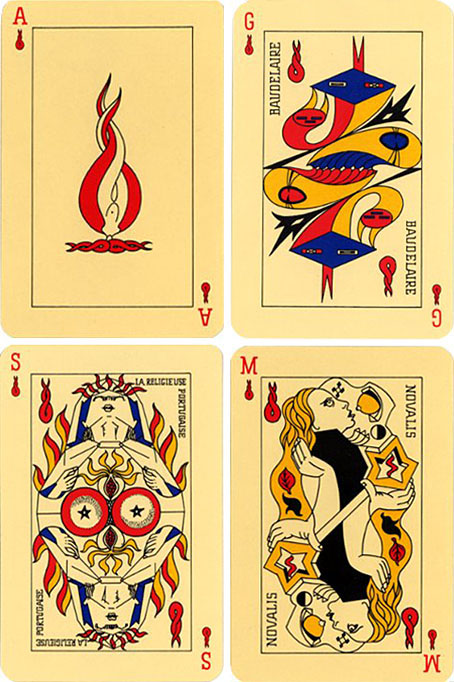

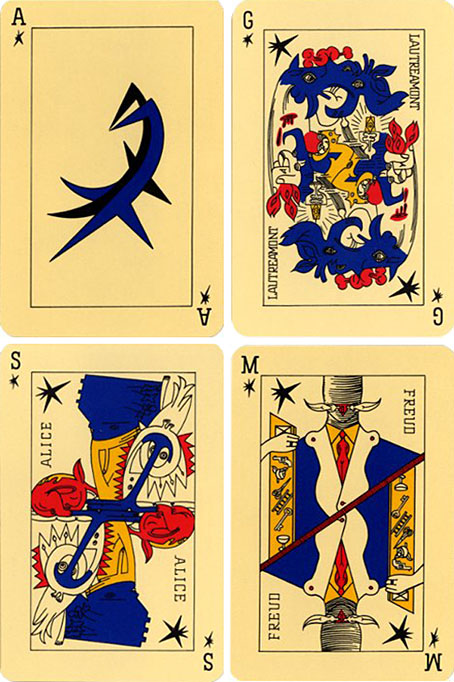

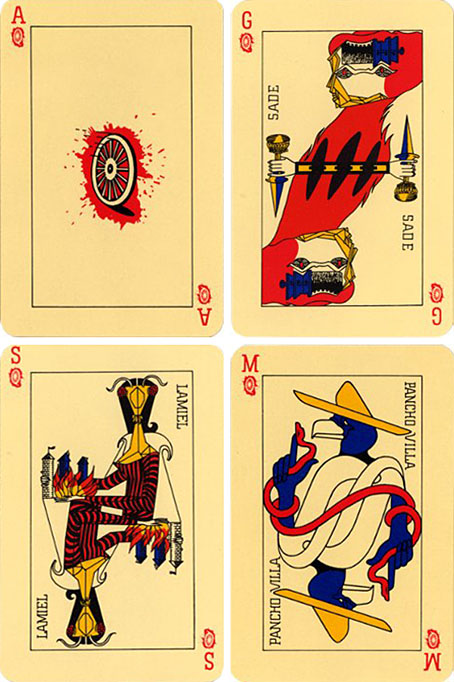

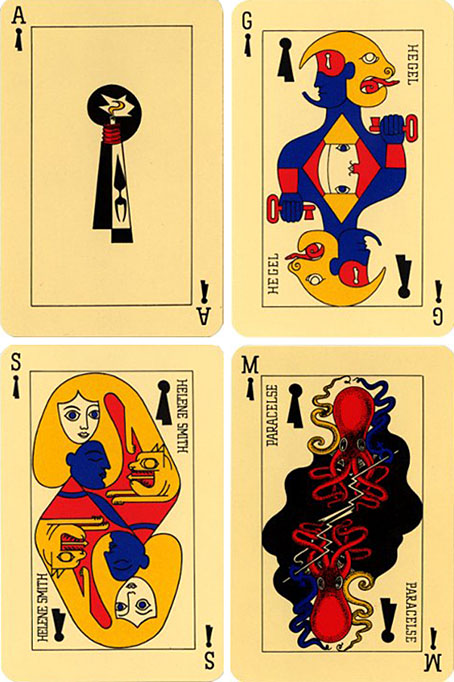

Reworking the illustrations of the standard fifty-two card playing deck has become quite a common thing in recent years with numerous themed decks being produced in costly limited editions. The same goes for decks of Tarot cards which have now been mapped across a number of different magical systems and produced in sets that often add little to the philosophy of the Tarot but merely vary the artwork. This wasn’t always the case, and certainly not in the 1940s when André Breton and a group of fellow Surrealists produced designs for a fascinating deck of cards that hybridises the Tarot and the more mundane pack of playing cards in an attempt to create something new.

Reworking the illustrations of the standard fifty-two card playing deck has become quite a common thing in recent years with numerous themed decks being produced in costly limited editions. The same goes for decks of Tarot cards which have now been mapped across a number of different magical systems and produced in sets that often add little to the philosophy of the Tarot but merely vary the artwork. This wasn’t always the case, and certainly not in the 1940s when André Breton and a group of fellow Surrealists produced designs for a fascinating deck of cards that hybridises the Tarot and the more mundane pack of playing cards in an attempt to create something new.