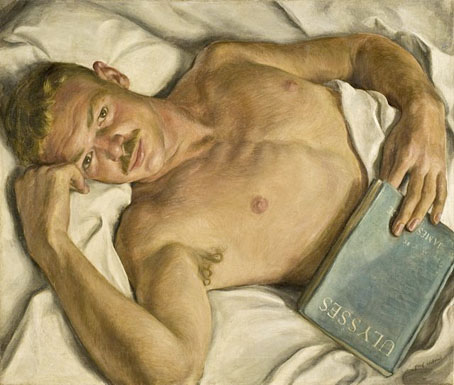

Jerry (1931) by Paul Cadmus.

• “I wanted to photograph naked young men as opulently and as attentively as those professional ladies appearing in Playboy-type magazines.” RIP James Bidgood, photographer and director of no-budget gay-porn classic Pink Narcissus. Also in the obituary notices this week: Monica Vitti and John Appleton, composer of electronic music and inventor of the Synclavier sampling keyboard.

• “…the Sola Busca deck is limited in its use for divinatory purposes today, and yet, since its enigmatic imagery irresistibly invites decoding, the deck nonetheless beckons twenty-first century cartomancers into a game of high imagination.” Kevin Dann on the mysteries of the world’s oldest complete Tarot deck.

• “This Missouri company still makes cassette tapes, and they are flying off the factory floor.” Jennifer Billock reports.

He attended to his own talent, not in the interest of bombast or self-aggrandisement, but rather like a faithful watchman. He had the fixity of the great and therefore no need of vanity. He estimated that three shillings would be a reasonable price for Ulysses. A tiresome book, he admitted. At the same time he was dogged by fear that the printing house would be burnt down or that some untoward catastrophe would happen. He assisted Miss Beach in wrapping the copies, he autographed the deluxe editions, he wrote to influential people, he hawked packages to the post office. He knew that the illustrati would change their minds many a time before settling down to a final opinion and that many another would know as much about it as the parliamentary side of his arse.

Edna O’Brien on James Joyce

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine on The Secret Glory by Arthur Machen, another novel now in its centenary year.

• At Aquarium Drunkard: It Is Not My Music, (1978) an hour-long Swedish TV documentary about Don Cherry.

• At Bandcamp: The transportive psychedelia of Moon Glyph records.

• Mix of the week: Fact Mix 844 by A Psychic Yes.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Show.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Guitar.

• Mumblin’ Guitar (1960) by Bo Diddley | Electric Guitar (1979) by Talking Heads | Impossible Guitar (1982) by Phil Manzanera