Chez Cocteau.

“Effects” in the sense of possessions rather than aesthetic or creative effects. I’ve been reading Jean Cocteau’s The Difficulty of Being, an essay collection in which the author muses on a variety of subjects, from his own life, his work, and people he knew, to more general considerations of the human condition. In one of the chapters Cocteau describes his rooms at 36 rue de Montpensier, Paris, where he lived from 1940 to 1947, offering a list of the objects that occupied the shelves or decorated the walls of his apartment. I always enjoy accounts of this sort; the pictures (or objects) that people choose to hang on their walls tell you things about a person’s tastes and character which might not be so obvious otherwise. The same can’t always be said for published lists of favourite books or other artworks when these may be constructed with an eye to the approval of one’s peers. The pictures decorating your living space are more private and generally more honest as aesthetic choices.

I already knew what a couple of these items looked like: the Radiguet bust, for example, may be seen in documentary footage. This post is an attempt to find some of the others. If you know the identity of any of the unidentified pieces then please leave a comment.

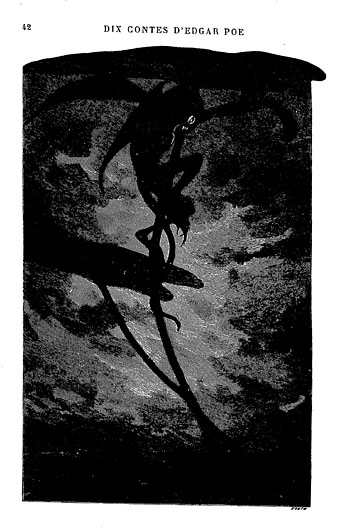

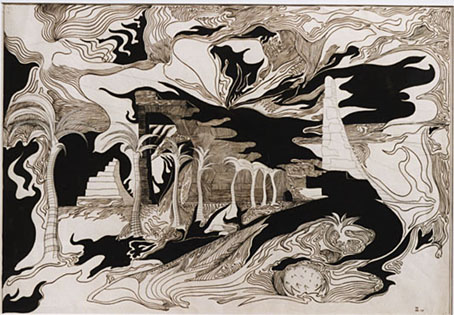

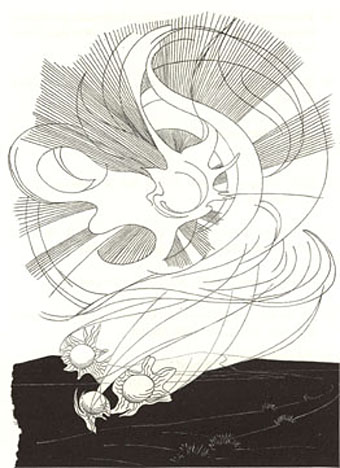

The most engaging bits of such wreckage, thrown up on this little red beach, is without doubt the Gustave Doré group of which the Charles de Noailles gave me a plaster cast from which I had a bronze made. In it Perseus is to be seen mounted on the hippogryph, held in the air by means of a long spear planted in the gullet of the dragon, which dragon is winding its death throes round Andromeda.

“the Charles de Noailles” refers to Charles and his wife, Marie-Laure, a pair of wealthy art patrons who helped finance Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or and Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète. Doré’s illustration (showing Ruggerio from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso reenacting the heroic rescue) is very familiar to me but I was unable to find any sculptural copies of the work. In addition to decorating Cocteau’s room some of Doré’s illustrations also served as inspiration for the sets in La Belle et la Bête.

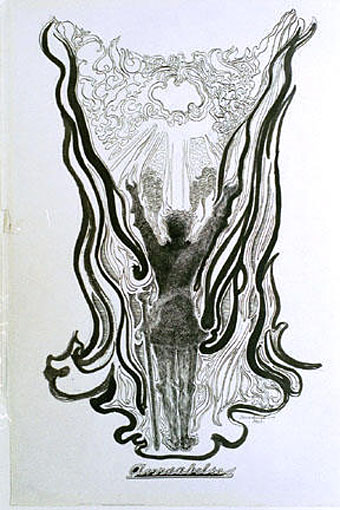

This group is on a column standing between the so-called castor window and a tall piece of slate that can be moved aside and that conceals a small room which is too cold to be used in winter. It was there that I wrote Renaud et Armide, away from everything, set free from telephone and door bells, in the summer of 1941, on an architect’s table above which one sees, saved from my room in the rue Vignon where it adorned the wall-paper, Christian Bérard’s large drawing in charcoal and red chalk representing the meeting of Oedipus and the Sphinx.

Bérard’s drawing is large indeed (see the photo at the top of this post). The artist was a theatrical designer, also the designer of La Belle et la Bête, and one of several of Cocteau’s friends who died young.

On the right of my bed are two heads, one Roman, in marble, of a faun (this belonged to my Lecomte grandfather), the other of Antinoüs, under a glass dome, a painted terracotta, so fragile that only the steadiness of its enamel eyes can have led it here from the depths of centuries like a blind man’s white stick.

A third head adorns that of my bed: the terracotta of Raymond Radiguet, done by Lipschitz, in the year of his death.

And speaking of premature deaths… Antinous was the celebrated youth beloved of the emperor Hadrian whose death by drowning in the Nile caused Hadrian to establish a cult of Antinous that spread across the Roman Empire. Many busts and full-figure statues survive as a result, but I was unable to find a photo of the one owned by Cocteau. Raymond Radiguet, meanwhile, died of typhoid fever at the age of 20. Radiguet was a precocious talent who managed to write two novels before he died, including Le Diable au corps at the age of 16.