Behold Nyarlathotep, v. 3.0, this being yet another revision of an old illustration. Some readers may recognise the imagery from version 2.0 (2009) or even the original that appeared in my Haunter of the Dark book in 1999. Earlier this month the work I’ve been doing for the new edition of the book reached the end of another stage with the completion of all the necessary redrawing of The Dunwich Horror. I’ve also just finished drawing page 24 of the story, the page I’d left half-done when the strip was abandoned in 1989. Everything I do from now on will be new material.

Having got this far I decided to pay a little more attention to the upgrading of the book’s fourth section, The Great Old Ones, by finishing Nyarlathotep, something I began this time last year then set aside when I got involved in rescanning all the old comics pages. As I’ve mentioned before, several of the pieces for this section of the book were some of my earliest digital illustrations, created a few months after I’d bought a secondhand and very underpowered Macintosh computer. Nyarlathotep was an attempt to depict the hybrid nature of a Mythos entity which combines elements of an Egyptian pharaoh, the diabolic “Black Man” of European witch cults, a sinister stage magician or scientist, and the winged abomination that Robert Blake finds lurking in the steeple of the Starry Wisdom church. Version 1 was one of my very first digital collages which suffered as a result of my inexperience with the new medium, hence my eagerness to rework the design in 2009 when Cyaegha, a metal band I’d been working with, requested a Nyarlathotep-themed T-shirt. The first version had been aimed more at the theatrical/scientific aspect of the character, with a poster in the background from John Nevil Maskelyne’s Egyptian Hall in London. For version 2 I added a number of organic elements to bolster the “Haunter of the Dark” side of the character. Version 3 keeps all the details from version 2 while replacing some of the collaged elements with similar ones taken from better sources. The new design is also slightly taller to account for the enlarged page size of the new book.

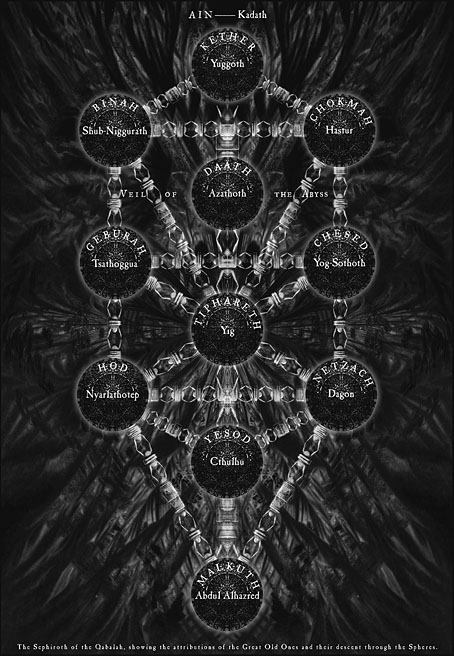

The Sephiroth chart from the second edition of the book, 2006.

The most notable additions to the new piece are the names of the character in Latin letters and Egyptian hieroglyphs (𓋔𓇋𓄿𓂋𓈌𓊵), the latter being a suggestion from this Reddit post. The Egyptian spelling is conjectural but I have a guidebook to the hieroglyphic language which confirms that most of the letters are the ones they should be. The words aren’t included solely as decoration. The Great Old Ones was a collaboration with Alan Moore in which Alan wrote eleven texts or invocations which position each god or entity on one of the spheres of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. Alan was heavily involved with the Kabbalah at this time, being also engaged with the first few issues of Promethea, a story which involves a physical (or metaphysical) journey from Malkuth to Kether. The Great Old Ones takes the same journey in reverse, and from a much darker perspective, like a Lovecraftian equivalent of the Qliphoth, the “nightside” of the Kabbalistic spheres. In Alan’s scheme, Nyarlathotep is positioned at sphere 8, Hod (or “Splendour”), a sphere associated with gods of magic and language like Thoth, Hermes and Mercury. I imagine most Mythos-acquainted occultists would agree with adding Nyarlathotep to this pantheon. In addition to being gods of magic and language, Thoth, Hermes and Mercury also serve as celestial messengers, a function which Lovecraft assigns to Nyarlathotep in The Whisperer in Darkness when one of the Mi-Go declares “To Nyarlathotep, Mighty Messenger, must all things be told.”

As for the rest of The Great Old Ones, I have four more of them still to be reworked, one of which, Abdul Alhazred (or Lovecraft himself) is almost finished. Further progress will be posted here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Lettering Lovecraft

• Weird ekphrasis and the Dunwich Horrors

• Kadath and Yog-Sothoth

• Another view over Yuggoth

• Nyarlathotep: the Crawling Chaos