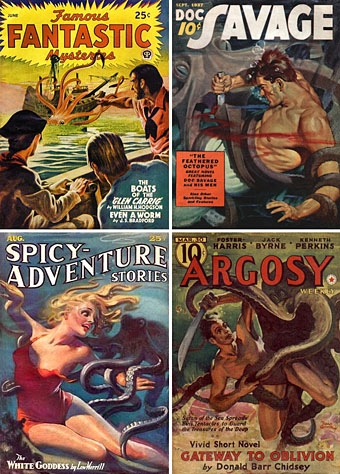

No, not Pirates of the Caribbean III although that film will be with us soon and is certain to contain at least one of the above ingredients. The dubious delights of exploitation cinema have been put back on the map recently by Grindhouse, the double feature from Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez, but garish melodrama is nothing new in the film world. Silent films had more than their share of sex, violence, monsters and maniacs, and many featured a degree of nudity that wouldn’t be seen again until the late Sixties, thanks to the Hays Code. “Everything in life is exploitation,” Barbara Stanwyck was told in Baby Face (1933) and she went on to prove it by sleeping her way to the top in a film considered by moral guardians of the time to be so scurrilous that its uncensored print remained buried until 2005.

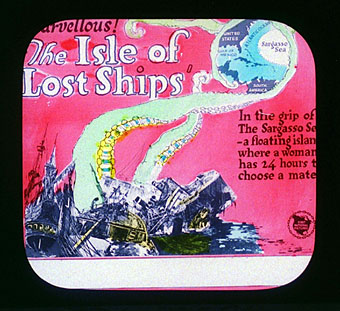

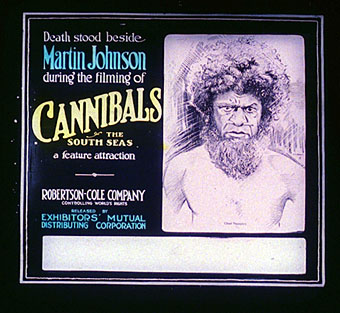

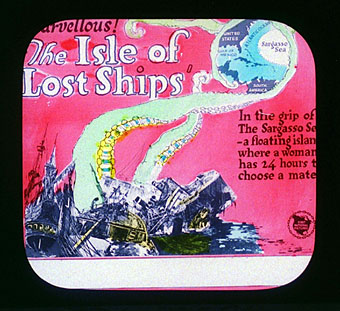

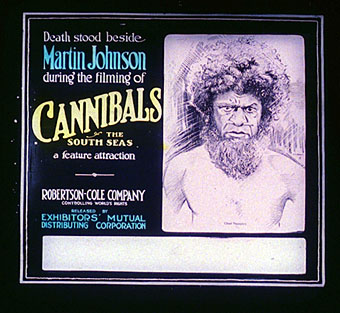

These wonderful hand-tinted plates from the George Eastman archive are lantern slides used to display information about coming attractions, and would have been screened between features as a kind of motionless trailer. The movie trailer as we know it today had been around since about 1910 but it wasn’t until the late Twenties that the regular production and screening of trailers took off. Lantern slides were a cheap way of keeping audiences attentive while the next feature was being prepared.

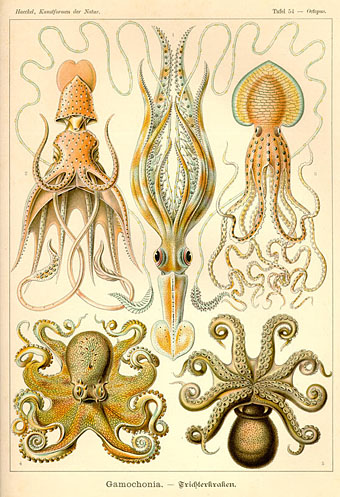

Cannibals of the South Seas was a 1912 documentary by Osa and Martin E. Johnson and it’s a good bet it was a lot more prosaic than this slide implies. The Isle of Lost Ships seems from the picture to be a sea-faring horror tale but turns out to be a 1923 adventure story based on a novel by one Crittenden Marriott and directed by Maurice Tourneur, father of the great horror and noir director, Jacques Tourneur (Cat People [1942], Out of the Past [1947], Night of the Demon [1957]). This first film is now as lost as the becalmed ships of its title but it was remade as an early talkie in 1929 and that film still exists somewhere. Film remakes are also nothing new. The tentacles and Sargasso setting made me suspect Mr Marriott had purloined an idea or two from William Hope Hodgson, writer of a series of excellent horror stories concerning the Sargasso Sea and (in his fiction) its population of tentacled abominations; Dennis Wheatley certainly stole from Hodgson, as I’ve mentioned before. But Marriott’s novel, The Isle of Dead Ships, and the films based upon it, prove to be less interesting than the slide promises. And so we learn a primary rule of exploitation cinema that was well-established even then: promise much but don’t always deliver.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Seamen in great distress eat one another

• Druillet meets Hodgson

• Rogue’s Gallery: Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs, and Chanteys

• Davy Jones