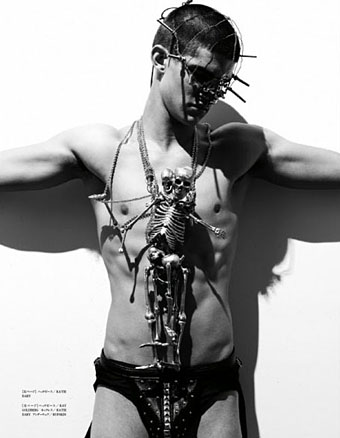

Two of the stunning displays created from sketches by David Lynch for the Galeries Lafayette department store, Paris. The series is entitled Machine-Abstraction-Women, and I don’t think Mr Lynch would mind too much having his description of the works translated in an extruded manner from French to English:

I was always fascinated by the spectacle of the women in front of the windows of the department stores. By designing the fronts of the Lafayette Galleries, I wanted to show all the identities which coexist at the woman of the 21st century. With the reflection of glass which returns the floutée image of the passers by, this set of parallel universes approaches my films, where the same actress interprets several characters. I drew very abstract decorations. Landscapes cubists populated of sculptures, wheels, pieces of furniture, of vidéos, sounds. I see these windows like a labyrinth, a street museum where to move through indices. A window, it is a transparent door on the unknown. (More.)

Much as I like Lynch’s films, I’ve never been very taken with his paintings, they always seem to lack the powerful quality he achieves in other media. But I like these a great deal and it’s a shame this is a one-off commission for a store. He’s also produced an attendant series of lithograph works, I See Myself.

• David Lynch aux Galeries

• David Lynch en vitrine

Previously on { feuilleton }

• David Lynch in Paris

• Inland Empire