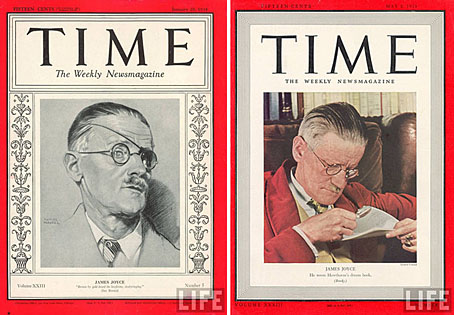

A post for Bloomsday. James Joyce made the cover of Time magazine on two occasions, each instance following the publication of his two greatest works. Ulysses was first published in France in 1922 but had to wait until 1934 to be presented in full to the American public after a trial for alleged obscenity. The edition for January 29, 1934 (left) included a review of the novel:

Is it dirty? To answer the man in the street in his own language, Yes. With the exception of medical books and out & out pornography, the only book of modern times that can compare with it for outspokenness in barnyard and backhouse terms is the late D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. But Ulysses is far from being “just another dirty book.” Judge Woolsey decided that its purpler passages are “emetic,” rather than “aphrodisiac”; that the net effect of its 768 big pages is “a somewhat tragic and very powerful commentary on the inner lives of men and women.”

I can imagine Joyce being amused (if not exasperated) by some of the ironies in this piece, not least for his novel having a “man in the street” as its central character, and that declaration, “Yes” (from the man in the street’s wife), being the very sign of affirmation upon which the narrative resolves.

Time for May 08, 1939 fares better in its review of Finnegans Wake although they still had to ask on behalf of the prurient reader: “Is the book dirty?” The answer? “Censors will probably never be able to tell.” Of greater interest is the description of the author which follows the review:

In appearance Joyce is slight, frail but impressive. He stands five feet ten or eleven, but looks as if a strong wind might blow him down. His face is thin and fine, its profile especially delicate. He wears his greying, thinning hair brushed back without a part. Joyce reads and writes sprawling in bed or on a couch but he does not like it known. He is very formal in public, in restaurants prefers straight-back chairs in which he sits bolt upright.

He dresses with conservative elegance, never goes out without a slender walking stick, which he manipulates expertly, accenting the delicacy of his beringed hands (he has a passion for rings). His voice is soft, rich and low with a gentle, melancholy brogue. He is rather vain of his tenor, which he likes to join with his son’s bass at small family celebrations.

For a list of Bloomsday events around the world, consult Google.