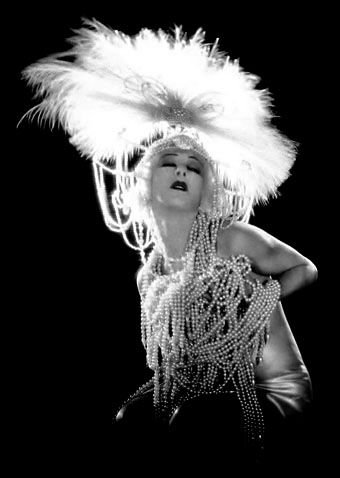

Alla Nazimova as Salomé (1923).

I wrote a while ago about Alla Nazimova’s luscious silent film production of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, a suitably Decadent affair with an allegedly all-gay cast, and costume and stage design based on Aubrey Beardsley’s celebrated illustrations. The film is currently touring England and Wales with a new score for four musicians by composer Charlie Barber, an extract of which can be heard here. I like the Middle Eastern sound of this, a shame the film isn’t coming to Manchester.

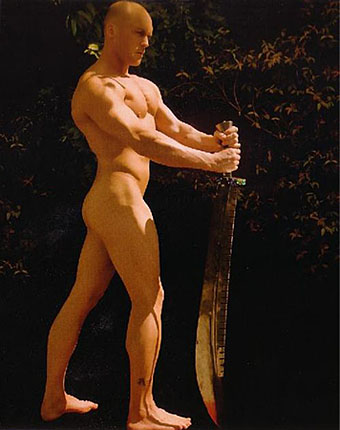

By coincidence, artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins sent these photos of an impressive Duncan Meadows and his equally impressive sword as additions to the burgeoning Men with swords archive. Meadows is shown as the executioner in a Royal Opera House production of the Strauss opera, appearing at the end of the drama bearing the head of John the Baptist. Given the way that Salomé’s body has always been the focus of attention in this story, Meadows’ appearance makes a striking change, one which Wilde himself might have appreciated.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The men with swords archive

• The Salomé archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Equus and the Executionist