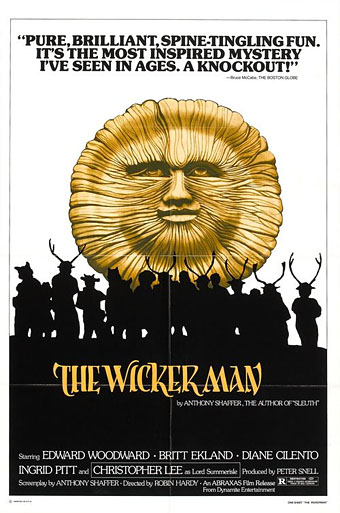

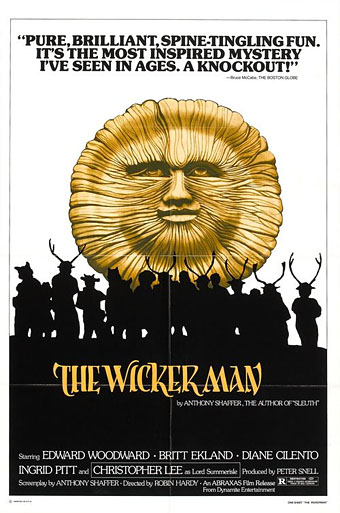

US reissue poster (1979).

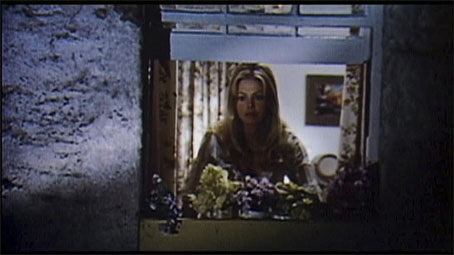

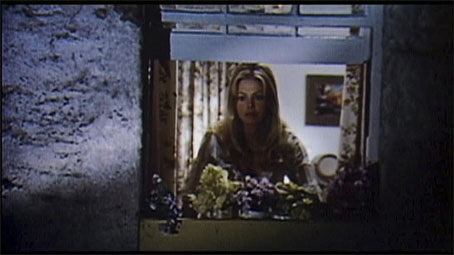

The restored version of The Wicker Man (1973) has been showing in UK cinemas recently, and the Blu-ray edition of the film is released this week. My copy arrived from Moviemail, and while I’m not in a great hurry to watch it again—this is one film that’s so familiar I could lip-synch along with it—it’s been a pleasure to compare the restored scenes to the long-version DVD which appeared in 2002. The earlier version had its missing scenes taken from a 1-inch videotape which was considerably poorer quality than the rest of the film. The restored scenes still look grainy and slightly washed out but now they at least look like pieces of film, not interpolations from video. The screengrabs below show the difference between scenes from the 2002 DVD compared to their equivalents on the Blu-ray. The rest of the film looks pristine, of course.

The new version isn’t as long as the longest version, however, a preliminary sequence in and around the mainland police station having been excised. In a lengthy feature in the October edition of Sight & Sound director Robin Hardy explains that he disliked what he calls “the Z-Cars section” (referring to an old UK TV series), and it’s true that it doesn’t help the story at all. Whether they like it or not, viewers of the film have to accept constable Howie as their proxy within the story, and he’s an insufferable prig throughout. That’s bearable in the context of his presence on Summerisle but the mainland sequence throws his character into relief against his less priggish colleagues.

Another slight omission is the title card which used to precede the film thanking Lord Summerisle and the islanders for allowing the filmmakers to observe their rituals. In its place we have a zoom into the face of Nuada the Sun God, a painted rendering of a carved figure seen in the film. I’ve always liked this face which has become an emblem of the film even though it’s not present in all versions. (For more detail about the tangled history of the various prints, see this site.)

Cover photo by Oliver Hunter.

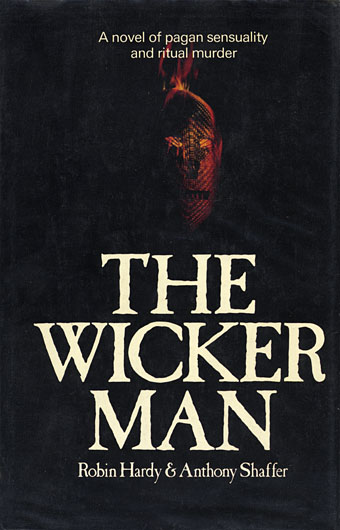

A rather bad drawing of the Nuada face appears at the beginning of each chapter of the novelisation which Hamlyn published in 1979 (and on the cover of the US edition from the year before). This was the year when the film’s reputation began to take off, and also the year it was reissued in the US. Although Hardy and screenwriter Anthony Shaffer are both credited for the novel I suspect the writing is mostly Shaffer’s work. It’s pretty good, and goes into considerable detail, fleshing out the story and Howie’s character, and also showing how much research the pair put into the pagan side of things. You also get the lyrics of some of the songs. Until the complete soundtrack appeared in 2002 the novel was the only place you could find the salacious missing verse from Willow’s Song which describes a maid milking a bull.

And speaking of the soundtrack, the three-disc Blu-ray edition includes the complete soundtrack on one of its discs, a considerable bonus if you don’t have it already. I should note that my good friend Gav insists I mention that the film’s final brass fanfare—labelled as Sunset on the soundtrack album—is a Bulgarian folk tune entitled Rodopska Devoika Zamrakanala Mona Jana, something neither of us has ever seen credited.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Children of the Stones