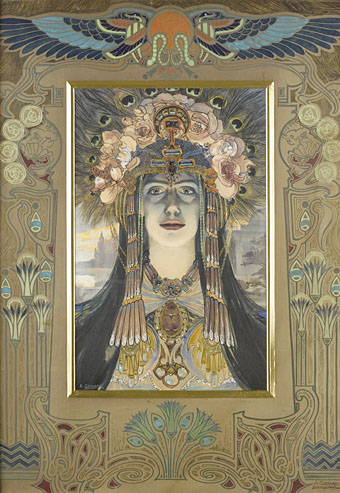

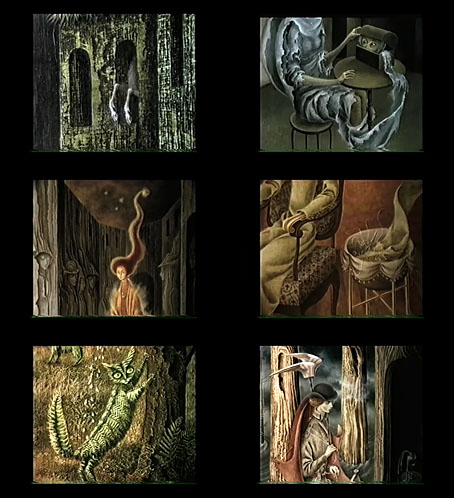

The Voice of St. Teresa (1928) by Oskar Sosnowski.

• The House is the Monster: Roger Corman’s Poe Cycle forms “a body of work not only deeply coherent but uniquely inspired,” says Geoffrey O’Brien.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Amberwood, while at The Daily Heller there’s a profile of Otto Bettmann, “an unsung visionary of commercial art”.

• At Public Domain review: The Works of Mars (1671), plans for military architecture by Allain Manesson Mallet.

The “underlying oneness of all things,” the conviction “that everything is connected” (Gravity’s Rainbow 703), is a thesis that appeals to many mystics and even to some scientists, but Fort complains that the latter too quickly dismiss unexplainable coincidences, or feebly explain them away. Scorning “scientific procedure” and inept police investigations, Fort turns for answers to denizens of the occult—poltergeists, invisible people, vampires, werewolves, miracle healers, fakirs, psychic criminals, dowsers—and to such notions as teleportation, human-animal metamorphoses, spontaneous combustion and pyrokinesis, “psychic bombardment,” telekinesis, animism, “secret rays,” telepathy, spirit-photography, clairvoyance, and modern instances of witchcraft.

Steven Moore in a perceptive essay about the overlooked connections between Thomas Pynchon, William Gaddis and Charles Fort. Having discussed Fort’s preoccupation with coincidences, the author notes that he shares a name with the late Steve Moore, former editor of Fortean Times magazine

• Pynchonesque headline of the week: The Paradox of the Radioactive Boars.

• James Balmont’s guide to the masterworks of New Taiwanese Cinema.

• New music: Solo for Tamburium by Catherine Christer Hennix.

• Winners of Bird Photographer of the Year 2023.

• Idris Ackamoor’s favourite music.

• Radio-Active (1984) by Steps Ahead | Radioactivity (William Orbit Remix) (1991) by Kraftwerk | Radioactivity (1998) by Hikasu